Needle exchange is increasing but appears to attract divided opinion. Is it a means of helping users and protecting the public, or are we fuelling addictions?

Needle exchange is about harm reduction and the most common means of ensuring this is providing drug users with clean and disposable supplies

Recently a wheelchair bound man gave a talk on his experiences with drugs to young people at a homeless centre in Cardiff. This man only had one leg. Why? Because he had continued to inject heroin into his groin. The talk concluded with him saying, “But at least I’ve got another leg to inject into.”

This man had been asked to talk by a Cardiff-based charity, with the hope his experiences would deter them from injecting into major arteries. Clearly his parting statement wasn’t what they had hoped he would say. However, it does demonstrate the power of a heroin addiction.

Needle exchange is nothing new; it was introduced across the country as a response to HIV in the 1980s. It’s a social policy whereby injecting drug users can obtain hypodermic needles and associated equipment free of charge. Until now needle exchange has remained below the radar but with a current increase in schemes more people seem to be asking questions about it.

It’s a contentious issue. On the one hand it’s seen as reducing the spread of disease and protecting the public. On the other hand, many see it as encouraging a drug addiction.

So is it a case of handing over the goods to people with substance misuse problems, or is there more to needle exchange than meets the eye?

The idea behind needle exchange

There are many elements to needle exchange but at the centre is the idea of harm reduction. Dave Chamberlain is the former chair and a current volunteer at Inroads Cardiff, a charity offering help and support to drug users. He said, “We’re not helping people take drugs we’re helping people not kill themselves. We’re helping people use drugs safely.”

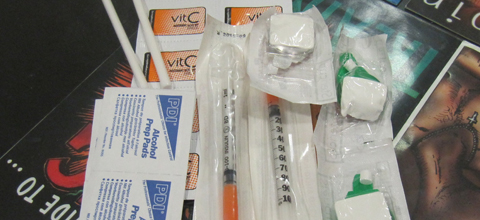

Inroads was established in 1996 after the need was identified in Cardiff for a street agency – an accessible service offering everything from information and advice to counselling and needle exchange itself. Inroads is now the largest needle exchange in Wales where drug users can access everything from hypodermic needles and mixing pots to swabs and filters. They’re also provided with sachets of acid, known as Vit C, to break down the heroin impurities – a preferable alternative to vinegar or lemon juice.

The Welsh Government’s Substance Misuse Treatment Framework (SMTF), estimates that there are around 8,000 illicit Injecting Drug Users (IDUs) in Wales, approximately 0.4% of the adult population in Wales. With this in mind, their concern is reducing blood-borne viruses.

A female heroin user, aged 30 said, “Needle exchange means I can get what I need, no questions asked. Then again, if I need to use I will, regardless of whether it’s clean stuff. I’m hep C positive so it’s game over for me anyway.”

The bit about quitting?

The service is free and only requires the user’s initials and date of birth, which is logged on a database. As it transpires, these details don’t even need to be accurate. So far it seems like the user comes in with a shopping list, where’s the bit about quitting?

One member of the public said, “You wouldn’t give an alcoholic person alcohol, would you? People would think it was total madness and I don’t see this as any different. You’re encouraging drug users to keep taking drugs and all the anti-social elements that goes with it.”

But Jill Coles of Cardiff Addictions Unit explains rather than just nagging people you provide them with information and allow them to ask questions. The relationship formed with the user is seen as a building block for potential help in the future. “It’s a big step for someone to walk through the door and say ‘I’m a drug user, I’m a drug user who’s a mother, I’m a drug user who’s a sex worker. Give me clean needles.’ It’s a big leap of faith on their side.”

Taking needle exchange a step further

While the mere concept of needle exchange remains contentious, Dave feels it should be progressing. “I speak for myself and a lot of practitioners that we would much prefer prescribed heroin in powder form that users can cook up in their pots and inject,” he says. This has been practised in Switzerland for the past three years.

What would be the advantage of doing this? Well not only would this be a cheaper alternative to methadone – the drug manufactured as a substitute to heroin – it would be of a consistent quality and strength, which according to Dave could potentially make the chances of kicking the addiction greater.

This would no doubt attract controversy. Jill explained, “The difficulty with heroin is, you get a buzz and people don’t like prescribing stuff you get a

buzz off.”

Aiding or alleviating a drug problem?

Both Dave and Jill are certain needle exchange is not simply a case of providing users with the tools to feed an addiction – it’s protection for the user and society. Several years ago you could have five or six users sharing the same needle and people were finding dirty equipment on the streets.

And it would seem the Welsh Government take a similar stance, with their Working Together to Reduce Harm strategy for 2008-2018 showing a continued commitment to needle exchange.

So is needle exchange simply about drug addicts getting what they want? Perhaps it’s best concluded with the words of a male user, aged 40, “Heroin has been part of my life for over 10 years but I don’t want it in my future. Catching something like hep C would cement it in my future. That’s why needle exchange is so important.”