Ahead of the launch of Cardiff crime magazine, Uncuffed, here’s a sneak peek of what to expect from the history page. This issue, Uncuffed will be focusing on Margaret Mackworth (later Lady Rhondda) and suffragette crimes in Wales. Dr Jacqui Turner and Professor Angela V John explain a bit about what the suffragettes endured to achieve the vote:

Were the suffragettes terrorists?

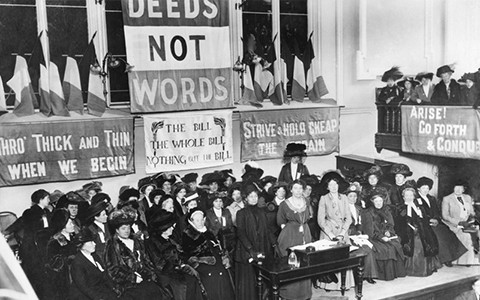

J: Technically some suffragette activity might be categorised at such , although I would have two issues with using that term. Firstly, the 21st century concept of terrorism cannot easily be applied to the end of the 19th and early 20th century as it has very different connotations today; the public perception of the perpetrators is also very different. It is also true that the vast majority of women’s suffrage supporters were also supporters of manhood or universal suffrage and did not engage in breaking the law. Much suffrage activity could be better described as a campaign of civil disobedience. The suffragettes of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) received disproportionate sentences for the crimes committed and demanded to be treated as political prisoners after their arrest.

In 1903, Emmeline Pankhurst helped found the Women’s Social and Political Union which used militant means to gain female enfranchisement

In 1903, Emmeline Pankhurst helped found the Women’s Social and Political Union which used militant means to gain female enfranchisementA: The term, terrorist, the terminology is emotive. Most people who supported the suffrage movement weren’t suffragettes (militant group). Most women were suffragists (peaceful campaigners). In Wales, there were more suffragists than there ever were suffragettes. There were more peaceful protests than those prepared to take dramatic action. They wouldn’t have perceived themselves as terrorists. They believed they’d been forced into it. They were denied the right to have a say in the running of the country. They had to draw attention to this. The Welsh women who were smashing windows in London, were not terrorists. There’s a line between property and people; there is a thin line. If dramatic action doesn’t achieve the ends you want, the next time you have to step it up and do something more dramatic. When they set people’s homes on fire, what if somebody was in the house at the time? They could have had casualties. Militancy escalates. There were many more peaceful women in Wales.

Do you think that the ends justified the means for the suffragettes?

J: Yes. It wouldn’t be right to say that the militant campaigns of the suffragettes were the only factor in the granting of a partial franchise in 1918, but there was an extreme reluctance on the part of politicians and society to go back to the days of militantly and imprisoning women after World War I. It was just time.

A: We’ve grown up with the vote. It’s hard to put ourselves in the shoes of those who were denied basic rights. The irony is, Pankhurst’s organisation didn’t ask for the vote for all women, only on the same terms as men. Working-class women wouldn’t have got the vote. It was only later on that all women got the vote. The WSPU didn’t advocate for all women. It wasn’t asking for the rights for all women. They wanted parity – equal rights with men. It wasn’t until 1918 that all men got the vote. Working-class women got involved because of propaganda. It was a catch-up situation. Many women believed that they would eventually have got the vote. Working-class women didn’t have as much time. Working-class women didn’t have the space and time that more middle-class women did.

How were suffragettes treated in prison?

J: Professor June Purvis has done an enormous amount of work on this and I cover it in my fun blog for BBC History Extra. However, in short, suffragettes were treated harshly in prison and in a manner that was, once again, disproportionate to their crimes – force-feeding could be inflicted on a prisoner who had merely broken a window. What is even more interesting is that women were treated differently depending on their class. June Purvis described the experiences of Lady Constance Lytton, who disguised herself as a poor woman named Jane Warton in order to gather evidence of differential treatment. Warton was “held down by wardresses as the doctor inserted a four-foot-long tube down her throat. A few seconds after the tube was down, she vomited all over her hair, her clothes and the wall, yet the task continued until all the liquid had been emptied into her stomach. As the doctor left ‘he gave me a slap on the cheek’, Constance recollected, ‘not violently, but, as it were, to express his contemptuous disapproval’.” She was forcibly fed seven more times before her true identity was revealed and she was released. Constance never fully recovered from her ordeal – she suffered a stroke in 1912 and died in 1923.

Margaret Mackworth was detained at Usk Gaol for attempting to blow up a Newport postbox with a homemade bomb

Margaret Mackworth was detained at Usk Gaol for attempting to blow up a Newport postbox with a homemade bombA: It changed over time. Many women went on hunger strike and got force-fed. It was a horrendous incident. Lady Mackworth (Margaret Haig Thomas, Viscountess Rhondda) who was at Usk Gaol; she wasn’t forcefully fed. There had been bad publicity over force-feeding in England, which left the women in a state after this. So the authorities became a bit wary about forcefully feeding. They passed the Cat and Mouse Act. Women who were in danger of dying from starvation were temporarily released and them re-arrested once they were better. The government were worried about people making martyrs of themselves. Lady Rhondda was released under the Cat and Mouse Act. She was meant to go back but an anonymous person paid her fine. There is speculation that the government paid the fine as she came from a very powerful and influential family, which could have been dangerous. The fine was paid without her permission which left her very angry. There were very few women detained in Wales. Welsh women were arrested in Holloway for smashing windows. It’s difficult to compute exactly. We don’t have precise figures.

How did the public view the suffragettes at the time?

J: That depended whether you were a supporter of Votes for Women or held anti-suffrage views. It also depended on whether you were a supporter of women’s suffrage but disagreed with the actions of the suffragettes, which was a position held by the The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) which had a far larger membership than the WSPU. The public perception of the suffragettes changed over time. Initially, appalled by the public actions of the ‘gentler sex’, anti-suffrage campaigners presented them as unnatural, failures in achieving their unlitmate goal in life – marriage and children. They were represented in the press as masculine, frigid spinsters or overbearing wives setting out to emasculate men. The softening or change in public perception was influenced by images of hunger striking women, the introduction of force-feeding, the Cat and Mouse Act in 1912 and an outstanding campaign by the WSPU on the horrors of force-feeding and the treatment of women purely because of their gender. Even those against Votes for Women were appalled by the state’s treatment of them.

A: Different people in different places reacted differently. They were often feared. They got a bit labelled and branded and people were weary of them and blamed things on the suffragettes. Other people set things on fire and blamed it on them. They became scapegoats for people wanting to cause trouble. Live mice were released on stage where they spoke, rotten tomatoes and sulphur acid were used to attack them physically. In North Wales, hooligans dragged them to the river and ripped their clothing and physically and verbally attacked them. There was even organised opposition against women’s suffrage. But, there were also men who were keen supporters of women’s suffrage. A Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage (MLWS) was created which used more direct action. But, this was mostly in England. Some people were converted. They came to see that women had a raw deal. The suffragettes were imaginative in their methods to reach people and win over converts.