In a time when there is growing interest in debutants, dowagers, butlers and bonnets, is the ‘Downton effect’ suffocating Welsh working-class voices?

King Coal once ruled the world, but has now been relegated to fuelling the minds of children in history books rather than powering the Industrial Revolution and helping win world wars. In the modern day, Downton Abbey is what keeps houses warm on Sunday nights. Instead of seeing men cutting coal in an underground cage, we see scullery maid, Daisy kindling the fires in the drawing room. As opposed to viewing steam trains transporting fossil fuels across the country, we see Lady Mary travelling first-class to visit a suitor in London. We see the Lord of the manor, not the miner.

Downton Abbey can draw in over 9 million viewers per episode, displaying the public’s interest in the lives of the aristocracy

Downton Abbey can draw in over 9 million viewers per episode, displaying the public’s interest in the lives of the aristocracyPublic interest currently lies in discovering the lives of the aristocracy –leaving the Welsh heritage sector facing a dilemma as tricky as running the Earl of Grantham’s estate. It must consolidate presenting the agricultural and industrial narratives of working-class Welsh people with supplying demand for debutants, dowagers, bonnets and butlers.

Pumping the heart of Welsh history

It is likely that if you were brought up in South Wales, you will have visited the Celtic huts at St Fagans, or travelled underground to retrace the sooty footsteps of the miners at Big Pit. These best-loved heritage sites are run by National Museum Wales (NMW) and are sponsored by the Welsh Government. According to Dr Ben Curtis, lecturer in modern Welsh history at Cardiff University, “Museums are deemed non-essential when compared with national security. They are on the frontline – in the firing line of austerity.” Shots were fired in 2014 when NMW were asked to cut £200,000 from its budget.

The Welsh Government is currently debating the Historic Environment (Wales) Bill, which hopes to preserve the past in a representative way. Yet, austerity measures have tightening the purse strings of local authorities – making it difficult to honour the past, and easier for independent museums to favour grand narratives.

Mining working-class voices

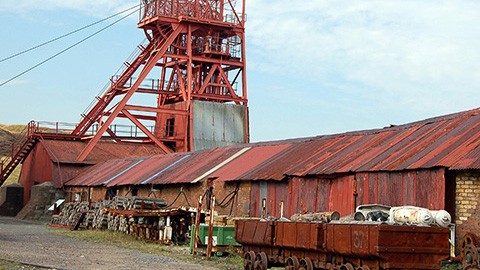

Big Pit exemplifies the difficulties of keeping the heart of Wales’ history pumping. Most Welsh people would be hard-pressed not to find a drop of coalmining in their blood. But, with growing interest in ‘upstairs’ life, how does the miner, who works 1,000 feet below ladies’ maids and first-footmen compete to be heard? “We’re more D H Lawrence, than Downton Abbey,” Ceri Thompson, a curator at Big Pit laughs. Since the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike, the National Coal Board has been unable to support the museum, coal mines in Wales have mothballed at an alarming rate and with them engineers who are able to keep pits safe. Therefore, blood flow to working-class narratives has weakened. The last deep pit coal mine in the UK is planned to close this week in Knottingley.

Big Pit displays the authentic voice of the working-class miners who helped fuel the Industrial Revolution

Big Pit displays the authentic voice of the working-class miners who helped fuel the Industrial RevolutionDespite these obstacles, Ceri is confident that Big Pit has an interesting story to tell and will continue to attract visitors. The museum presents all aspects of mining life from cutting and transporting coal, to political involvement, human cost, illness and poverty. “We display things through a miner’s eyes,” he enthuses. “We’re all ex-miners here or have links to the coalface. We’re a community museum – a people museum,” which makes its narrative authentic. He calls independent museums “vanity projects.”

The ‘Downton effect’

There is no denying that these ‘vanity projects’ are flourishing. The National Trust is the largest visitor business in Wales. Roughly 1.2 million paying visitors visit a National Trust site each year, with Welsh sites already seeing an approximated 14% increase in visitor figures this year. These sites have made efforts to tap into the mine field of working-class histories, but most properties follow an aristocratic narrative. Until recently, Penrhyn Castle in North Wales made no mention of the family’s involvement in the slave trade. According to Alun Prichard, The National Trust’s consultancy manager for North Wales, “We shouldn’t airbrush the past. We need to be honest.” The ‘Downton effect’ coincides with fascination with the common man, allowing two parts of a whole story to be told. Alun explains that although he welcomes increased interest in National Trust properties, “We wouldn’t want to Disney-fy something.”

Fonmon Castle is the longest continuously inhabited castle in Wales and has provided an aristocratic narrative for almost 1,000 years

Fonmon Castle is the longest continuously inhabited castle in Wales and has provided an aristocratic narrative for almost 1,000 years“We wouldn’t want to Disney-fy something.”

Sir Brooke Boothby, owner of Fonmon Castle and vice-chairman of the Historic Houses Association in Wales believes all narratives should be recorded, but recognises not all will be remembered. Despite his ancestors being “comprehensively dependent” on working-class staff, little evidence of their lives exist as they could not read or write. Brooke considers that history will always be slightly unbalanced. “Cardiff Arms Park will always have a connotation of the likes of Gareth Edwards, Barry John and the great players who played there,” and not of those who built it, he explains.

[youtube width=”480″ height=”300″]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7iiDbPIH_y0[/youtube]

King Coal no longer rules the world. He has surrendered his throne to Lady Mary. Its kingdom was not usurped, but toppled by economic uncertainty and an exodus of expertise. In reality, Downton’s popularity coincides with a bottom-up approach to history and retrieving the long-forgotten whispers of the working-class. It has further highlighted the disparities in narratives and has sparked negotiations between the custodians of the past and the exchequer. The Downton debate might yet ensure that children continue retracing the sooty footsteps of the miners, instead of kindling the fires of ignorance. History books of the future could see the Lord of the manor standing alongside the miner.