It’s a chill and sunny Saturday in December. The Cardiff Market is bustling with people in their hats and jackets, some sporting Wales scarves. Breath is seen as vapour in the chill air. An eight-year-old American boy, travelling with his parents, poses on the steps with his tongue out, hamming it up for a camera. His father is reading the menu at the cheese counter. His mother is scanning another booth for possible gifts. Wales’ rugby team will be playing South Africa in a few hours… but these three will not be attending.

They won’t be attending the game because Harry, the eight-year-old boy, is not interested in loud crowds or sports. Harry has Asperger’s syndrome, a disability on the autism spectrum. For him, watching a game in a stadium would be akin to torture.

A rugby game in a large stadium is something they wouldn’t even consider back home but travelling exposes people to new experiences, and new challenges. “We try to keep the routine as much as possible. But a learning experience is also to break that routine.” Harry’s dad, Matt, says.

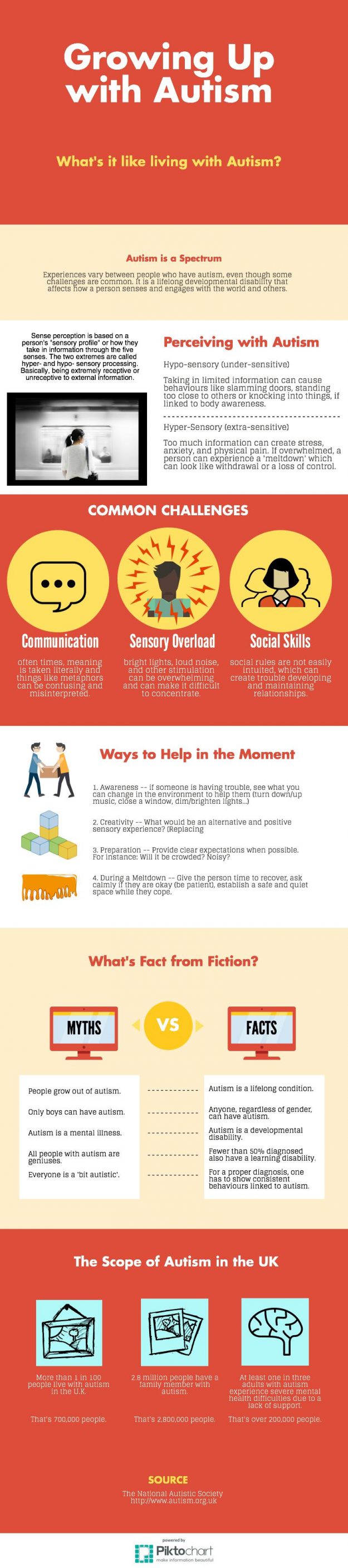

For people with Asperger’s, overstimulation is problematic, which makes travelling a challenge. It’s not just a noisy crowd, it’s an augmented cacophony of sounds and a claustrophobic corral of human bodies. That’s because people with this disability don’t have an information filter that someone who isn’t on the autism spectrum would typically have.

“Lots of people just block out whole swathes.” Harry’s mum, Mary says. “You block out all these people and you only see shops. You’re sitting in a room of people at a coffee shop and you’re talking to one person. You don’t hear anything else. I believe Harry hears everything. He sees all those people. He sees the lights. He sees hawkers selling giant daisy faces. It’s all a bit much.”

Instead of the game, they went to see the Roald Dahl exhibit at Millennium Centre. The three of them have read handfuls of Roald Dahl’s stories together over the years. For the most part, Harry enjoyed it.

“It lets you learn about Roald Dahl while making it in a fun way,” Harry says.

In one of the rooms, ‘dream jars’ hung outside an attic window. Audience members were invited to speak their dreams into a horn that was lodged into the wall. The jars would light up and twinkle at the sound.

Harry did not share his dream. “But one of the funniest parts was when it really glowed when someone said bananas as a dream,” he laughs.

Until recently, Asperger’s was a separate diagnosis to autism. In 2013, the DSM-V, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, merged Asperger’s into A.S.D: autism spectrum disorder. This move was sparked by roughly ten years of advocacy work and research.

Even then, Asperger’s used to be seen as high-functioning autism. Now, there has been a shift from focusing on ‘functioning levels’ to ‘communication profiles.’ This means that instead of seeing people as “high-functioning” or “low-functioning,” which assumes cognitive ability, the primary factor is how someone is able to communicate, and how reliable that communication is.

Elizabeth Stringer Keefe is a professor at Lesley University in Boston. She has been researching Autism for over 20 years.

“Almost every approach to early intervention in autism in the U.S. involves a heavy approach to communication support, whatever that might be. Without reliable communication we’re basically guessing at people’s needs,” Keefe says.

Harry was diagnosed with Asperger’s when he was four. His parents say their immediate response was to get him the help he needed. They researched schools that would better suit Harry’s needs so that he has supported learning, which now includes advanced learning material on mathematics. They’ve instilled daily routines that work with Harry’s condition, with reminders of those rituals taped next to light switches.

“I think it adds to his personality a unique dimension and I don’t want to erase that completely,” Harry’s dad, Matt says. “But I want to make him so he has a happier life. So I think we need to not eliminate those things but to—”

“—Be able to fake it in society enough to get by,” Mary says, finishing her husband’s sentence. “He wouldn’t be able to get ahead in the workforce. He would have a very difficult time in college…. He just needs to fake the social skills. That’s fine. More people should try to fake social skills.”

Their approach reflects new research on early intervention techniques for communication support. Families who received support learned methods of communicating with autistic family members that improved all parties’ quality of life.

“Highly individualised approaches are really critical for people’s communication development.” Professor Keefe says. “The key is finding an approach that is motivating to the individual and helps them to prioritise their needs or articulated desires.

In Harry’s case, the trouble is in tactful communication. “I try to have Harry ask questions especially when it pertains particularly to him,” Mary says. “If he wants a plug to plug in his phone, I will have him ask and now he knows if he asks more politely he is more likely to get a plug, which is what he wants.”

In Harry’s case, the trouble is in tactful communication. “I try to have Harry ask questions especially when it pertains particularly to him,” Mary says. “If he wants a plug to plug in his phone, I will have him ask and now he knows if he asks more politely he is more likely to get a plug, which is what he wants.”

This comes up quite a bit while travelling, a pastime that connected Matt and Mary initially. “One of the reasons we decided to have a child was that we could share all of the wonderful things that we found out here,” Matt says.

Plans changed when Harry’s diagnosis became apparent, but they weren’t abandoned. His parents started by taking Harry with them to Iceland, a five-hour flight. They’ve been to Europe and Britain with Harry before, but hadn’t visited Wales until now.

There are a few considerations they take into account when travelling with Harry. They prepare him with what he can expect, which Mary says is a balance between too much and too little information. They also consider his needs. Even though they landed in London, they stayed in a smaller town to rest, where it would be quieter and less hectic.

Not only do Harry’s parents provide a forecast for their son, they alter their route to account for his interests, which don’t always match theirs. Incidentally, Harry and his father don’t share the same love of art. Harry has a mathematical mind and a desire to go into engineering, something he says he decided on between the ages of two and three. However, Matt’s background is in graphic design and he and Mary see great importance in creativity and culture.

“I would hope it would be part of his existence to be creative in whatever he does,” Matt says.

“On the flip side,” Mary says. “If you have to choose something for your child… starving artist? Successful engineer? Many people would say that being a successful engineer would be the most positive, good thing that you could possibly want. As opposed to a creative artist who was only successful after they were dead. So –”

“So the things we’ve avoided are art museums,” Matt says.

Instead, one of the places they visited was Cardiff Castle, which to Harry was a fine piece of defensive engineering.

“We could visualise it, and touch it, and feel it. It’s not like a museum where you just look, look, look,” he says. “There’s an audio tour. It’s like you listen to what’s going on. You decide what you’re going to listen to, but you should probably follow the [instructions].”

In other places where they’ve travelled, Matt and Mary have explored some aspects of cities that they would have never considered before.

“I don’t know that we would have gone to see the inner workings of the Tower Bridge or would have paid so much attention to the way the Eiffel Tower is built… and hydraulics and the scientific part of it so we’re on the benefit of it too,” Matt says.

“I’m learning to look at the world in a different way through his eyes.”

To learn more about Matt and Mary’s approach, see here: INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT