As the Islamic month is observed worldwide, how do students fast while navigating academic pressures, part-time jobs, and a longing for family?

The sky is turning dark, and Sadia is organising baked bean cans during her shift at Tesco. She is supposed to break her 12-hour fast with a meal at sunset, but her shift doesn’t end until 8 pm. She’s come prepared, though. There are dates in Sadia’s bag. She’ll have a few with water for now. A proper dinner awaits her once she’s home.

Thousands of miles away, in Multan, Pakistan, the sun set long ago. Sadia’s family have already broken their fasts. Her mother sent her pictures of the dishes she’d cooked, everything Sadia had grown up eating with her family. Everything that she misses.

“I never realised how lonely and tough spending Ramadan away from your family could get until I went through it,” she says. “It was always magical, but not anymore. Not as an international student, at least.”

Sadia is one of many students from Muslim countries who’ve come to study in the Welsh capital. These students bring not just career aspirations but also fragments of experiences from their homelands, like celebrating the month of Ramadan with the rest of the Islamic world.

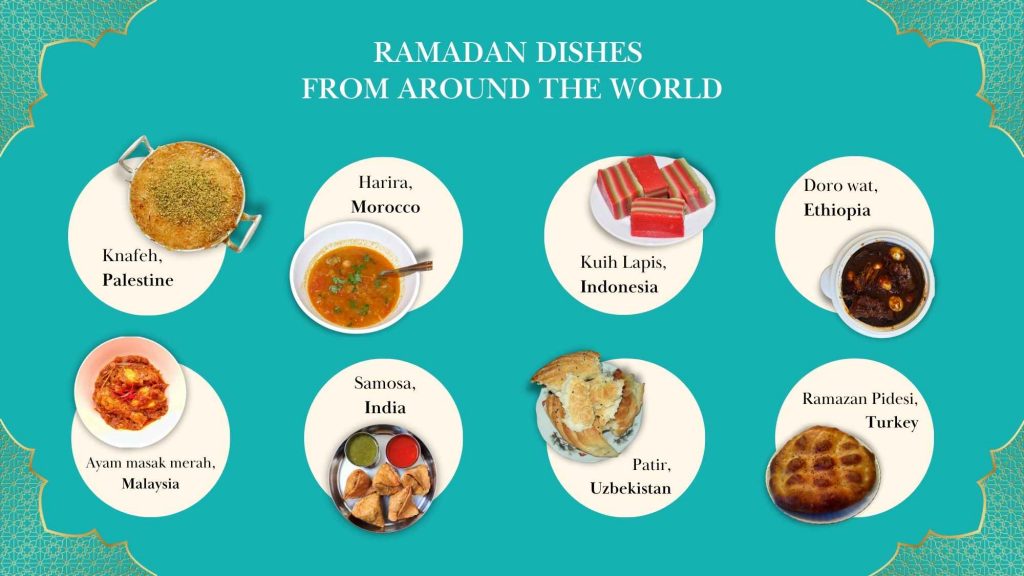

Ramadan is the ninth month of the Islamic calendar. During this month, Muslims fast between sunrise and sunset to reflect on the sufferings of the poor, among other religious reasons. They begin their fasts with suhoor, a meal consumed at dawn. Later in the day, at sunset, Muslims gather to have iftar, a meal eaten to end the day’s fast.

For Sadia, the joy of Ramadan boils down to two things: family and food. “You wait to eat all those pakora, samosa and chana chaat during Ramadan all year long,” she says.

“You can have them other times of the year, too, but during this month, they just hit differently. Maybe because everyone comes together to eat them, everyone’s so excited to eat everything on the table after a long day of fasting.”

Far away from family and everything familiar, Mohammed Ali Mahdi, from Lucknow, India, struggles to recreate the excitement of Ramadan given his busy schedule.

“It’s a bit challenging as well as exhausting,” he says. “I have to break my fast during my work before I come back home and have a proper meal. Apart from that, you have to wake up, eat suhoor and then wake up again for either work or classes.

Oftentimes, because of how packed Ali’s routine is, he ends up having iftar and suhoor all by himself.

He longs for his hometown during Ramadan. Lucknow is where the fusion of Indian and Persian culinary heritage birthed dishes cherished across South Asia, be it Pakistan, India or Bangladesh.

The city is buzzing with energy in the early hours of the morning when families, usually asleep at that hour, head to restaurants for suhoor.

“There are famous restaurants there where we eat kebabs and sheer-maal and all the dishes Lucknow is known for,” he says. “If you go there at two or three in the morning, you will find 100s of people gathered there.”

In Cardiff, going to restaurants for Iftar or Suhoor isn’t as easy as it is in Lucknow. “Many have fixed budgets,” says Ali. “They can’t eat out every day. It’s pretty expensive here in the UK. So, you have to make iftar on your own, no matter how tired you are.”

Maram Abdel Samad from Mansoura, Egypt, also misses how Ramadan is celebrated back in her country.

In Egypt, no matter which city you’re in, the streets come alive at sunset. Families organise ‘mercy meals’ in their neighbourhoods, setting up long iftar tables laden with food for relatives, friends, and neighbours to break their fasts with.

“Ramadan is so much more colourful in Egypt than it is here. You have family gatherings. You have more Ramadan-themed decorations,” she says.

Maram’s Iftar meals are very different from the ones she has back in her country. “If I’m preparing the food, I usually make wraps, something really quick to make,” she says.

“I have a part-time job, and sometimes the timings are six to nine, during which Iftar falls. So, I make my meal, take it with me and eat it during the shift. It is either this or I just go to the mosque and eat something served there.”

Maram believes that, in the absence of family, it is helpful for Muslims to find like-minded company. “I would advise students to visit Islamic centres around Cardiff during Ramadan,” she says.

“Yes, you’re missing your family. Yes, it is not the same. But it is going to make you feel much lighter if you have friends around you. Even if you don’t have any friends, and you’re going for the first time and feeling awkward about that, I’m pretty sure you’ll meet someone new you can get along with.”