As one Welsh community is displaced by rising sea levels, a Swansea glaciologist explains why we must protect our frozen freshwater and how we all have a role to play in water sustainability.

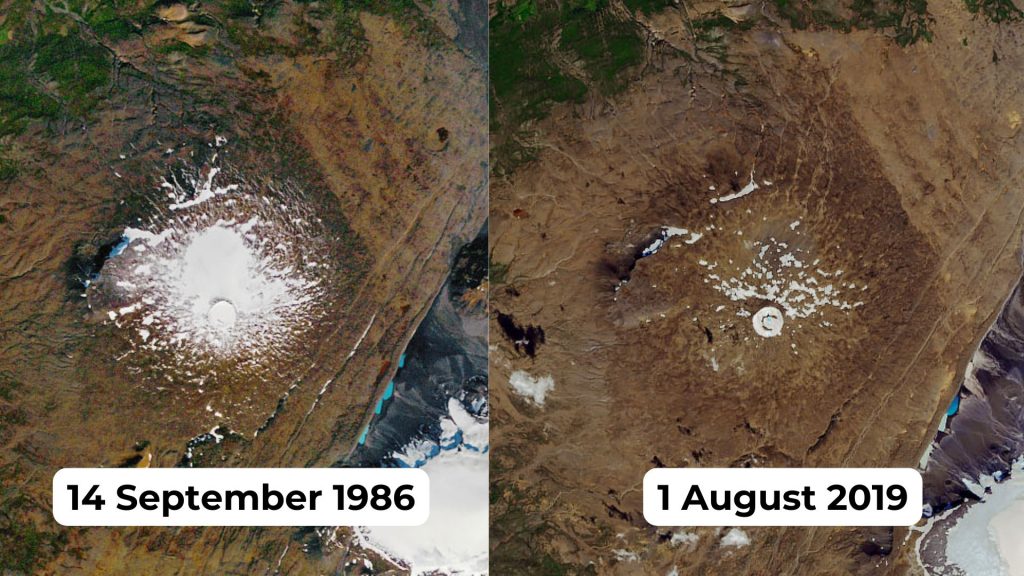

In 2019, a funeral party gathered at the base of the Ok volcano in western Iceland. Donning sturdy boots, warm bobble hats and colourful waterproof jackets, around 100 mourners began the two-hour hike up the mountainside to the ceremony site. After poems and speeches, a memorial plaque was laid on a bare rock dedicated to Okjökull, the deceased. Part of the inscription reads, “This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it”.

Okjökull was the first of Iceland’s glaciers lost due to climate change. Hundreds of years old, it was officially declared dead in 2014. Once a mighty presence, it gradually declined in recent years and quietly disappeared. “A good friend has left us,” said one Icelandic glaciologist. In a country where ice is the international namesake, glaciers are more than geographic landmarks. They have a place in culture, featuring widely in poetry, folklore and oral histories.

Icelanders mourn the death of Okjökull. But it is not just their loss. Glaciers play a crucial role in the global water system and their disappearance should concern us all. For Dr John Hiemstra, a glaciologist at Swansea University, “the importance of glaciers cannot be overemphasised”. He is part of an international community of scientists working to understand glacial processes and “preserve the vital roles that glaciers play in the climate and hydrological systems”.

Glaciers are massive bodies of ice that move slowly under the influence of gravity. They are found at high latitudes in the Antarctic and Artic but also in alpine or mountainous regions like the Himalayas, Andes and Alps. Each year, they lose mass during the summer through meltwater which is then recovered during winter snowfall and freeze. But for this to happen they need to stay cold enough all year round. Due to warming global temperatures, glaciers are now melting at unprecedented rates.

Iceland is the only country to have held a glacial funeral so far, but the impacts of global glacial retreat and melting ice are already affecting communities around the world. Even in Wales, which hasn’t seen glaciers for millennia, some of these changes are well underway.

“Disappearing glaciers contribute to sea level rise, which is something that people in Wales are already affected by… see Fairbourne” says Dr Hiemstra. In 2013, residents of the coastal village in north Wales were informed they would become the UK’s first climate refugees. The local authority, Gwynedd Council, had determined that managing the flood risks posed by sea level rise and inland flooding would soon become unviable. It was decided that the 450-home community would be “decommissioned in 30 years” through a managed retreat which is set to begin this year.

Fairbourne will not be alone in its fate. It is just one of hundred of coastal areas and island nations around the world on the frontlines of sea level rise. But glacial decline is not just a concern for low-lying communities. It also poses a significant threat to our global freshwater supplies, best understood as the water needed by humans, plants, animals for drinking and the production of food and energy.

“Glaciers provide a source of water to people that can be used for drinking, irrigation and hydropower” but “there is a limited supply of freshwater that can be used for people’s needs,” says Dr Hiemstra. Freshwater makes up just 2.5 percent of the world’s water, and glaciers help manage its availability by storing and slowly releasing it into rivers and lakes.

“There is fresh water in rivers and streams and lakes, and also in the ground. However, most of the world’s fresh water is held by glaciers and ice sheets. Estimates range from 65 to 75 percent. We need to look after this supply, and make sure that much of this water does not end up in the global ocean.”

This is also the key message from the United Nations for World Water Day 2025 (March 22).

Dr Hiemstra says, “It is clear that our changing climate directly affects all glacial systems on Earth. It is also clear that we, as humans, are largely responsible for the changes that are happening today in Antarctica and Greenland, and for the ongoing and projected disappearance of most, if not all, alpine glaciers.”

“Limited [supplies] of irrigation water will impact future crop production. Disappearance of glaciers could thus in the long-term drive-up prices for agricultural products and other goods, so that is something that could be felt by people in the UK and Wales in the near future.”

Tackling climate change and achieving net-zero will be critical to ensuring sustainable freshwater supply and management for everyone in the long term, regardless of geography. “Ultimately, that is what could stop and eventually reverse the loss of glacier ice,” says Dr Hiemstra.

The good news is that when it comes to water, there are many things we can do at home and in our local environment to support this bigger effort. Consuming less and reducing our carbon footprint is part of this. But so are simple actions to reduce water waste like running taps less, reusing water, promptly fixing leaks, and only boiling the water you need in the kettle.

Clearly, freshwater should not be taken for granted, even in a country like Wales famous for its high rainfall. Water is a shared resource, and being mindful how we use and waste it is one part of a complex global picture. While small steps may seem modest, they do play a crucial role in addressing our water challenges. Just as the funeral of Okjökull spoke to humanity’s shared connection with our natural environments, becoming more conscious of water in our homes and communities may help us appreciate this vital resource and see it, and ourselves, in a new light.