It’s the 40th anniversary of the end of the UK miners’ strike. What legacy does it leave, and what can we learn from it today?

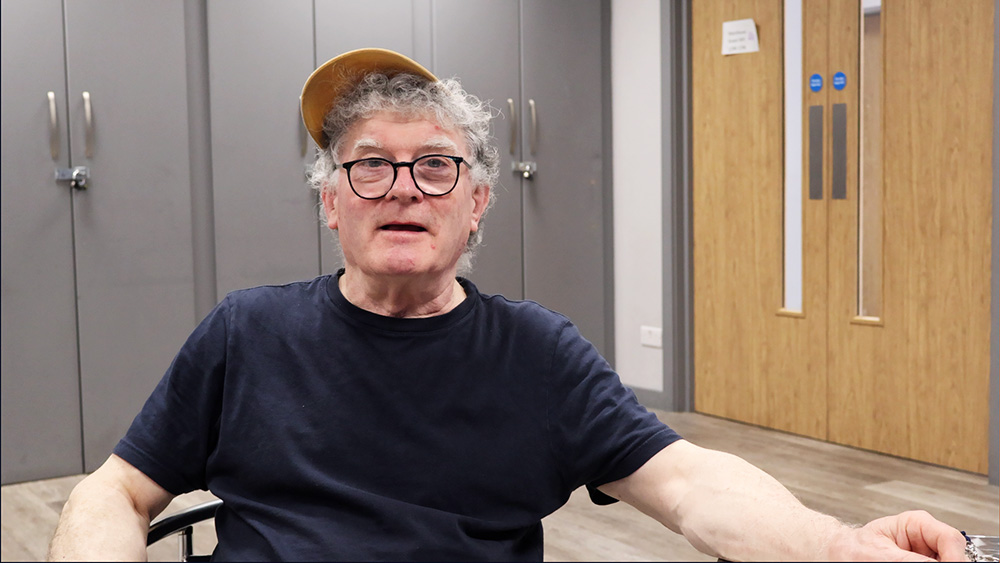

Terence Dimmick was born and grew up in a coal-mining family. His father started working underground at the age of 14, following a tradition that had shaped communities across South Wales for generations.

Instead of following his father into the dark tunnels of the mine, Terence chose a different yet related path. He participated in the mining process by making films. However, He did not realise that he captured the turning point in British history at that time.

“We weren’t just filming protests, we were documenting a way of life on the brink,” Terence says. “Most people outside the valleys had no idea what was really happening. We wanted to show it from the inside.”

As the UK marks the 40th anniversary of the end of the miners’ strike, Terence rescreened his co-created films in Cardiff’s Chapter Art centre to commemorate this year-long industry dispute.

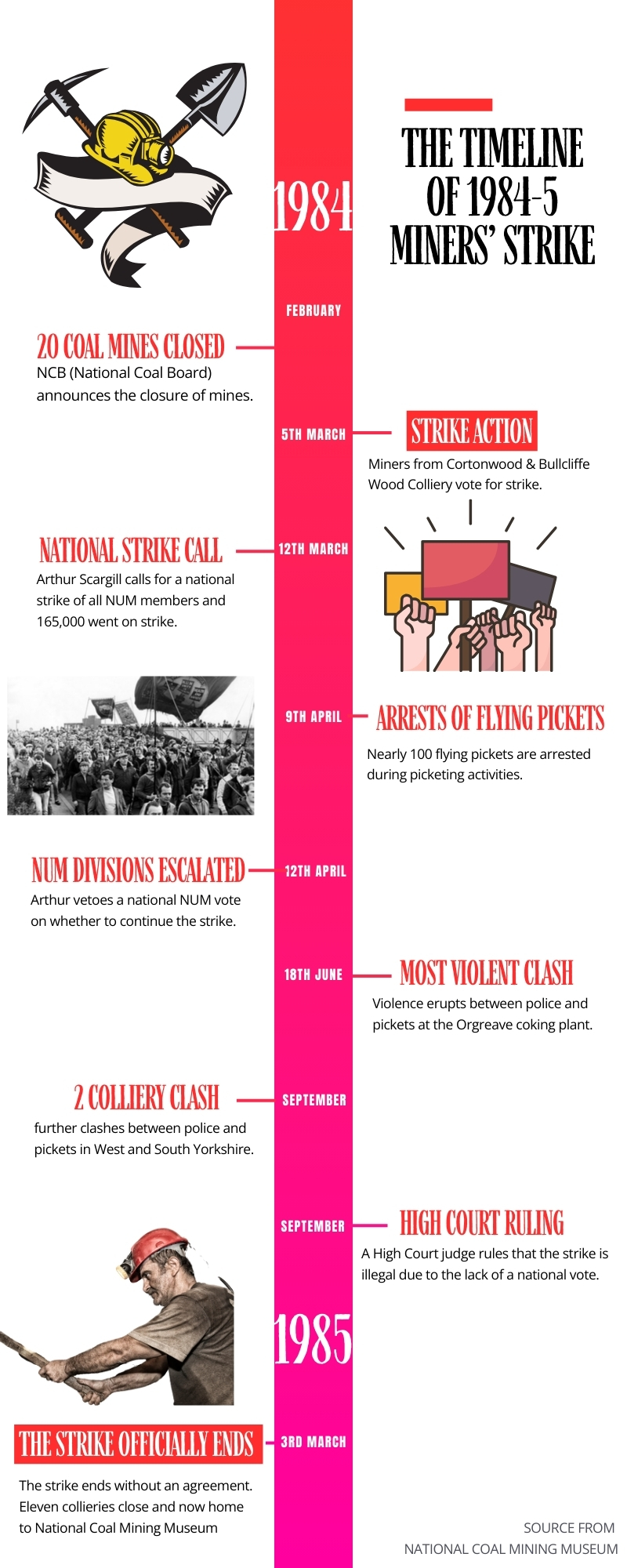

Miners’ strike was part of a broader strategy by the Thatcher government to crush union power, targeting the most organised and militant group within the unions, the miners.

“The government, as well as organising the police and the army, were manipulating the mainstream media in terms of press releases,” Terence says.

So, the project for him is not just about filmmaking but also about protecting ordinary people, especially miners and their families, who have a chance to tell their own stories on their own terms.

“We didn’t trust journalists, not during the strike,“ Terence says, “But then, suddenly, we were met with journalists in Wales who came from the same backgrounds as us. Their dads were on strike with us, their brothers, sisters, even their wives were on the picket lines too.”

This push led many British collectives, including Cinema Action, independent filmmakers, and the striking miners themselves, to pick up cameras during the late 1970s and 1980s to document narratives that were rarely seen.

“We’re waving a flag for a footnote about the industrial history,” Terence says. “And if you look back critically through the lens of a historian, history will speak for itself.”

According to a history study, many national newspapers reinforced the government’s framing of the strike, often portraying miners as violent and unlawful, while positioning police responses as justified efforts to restore order.

The miners’ strike lasted for 12 months, involving over 140,000 miners across the UK, What began as an industrial dispute soon escalated into a national confrontation between the government and organised labor.

“One of the things that needs to be remembered is that it was the biggest industrial struggle, only the second really significant one in the 20th century,” Terence recalled. “The first was the General Strike in 1926.”

Sian James, who was a miner’s wife raising children in the Swansea Valley, went on to become the first female MP for Swansea East from 2005 to 2015. The strike was also about community integrity for her.

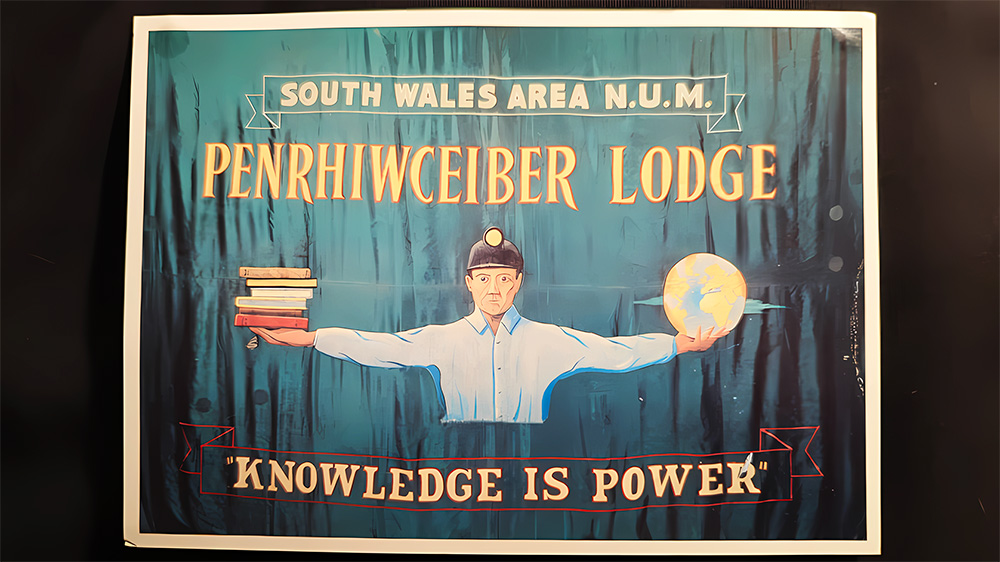

“We knew what we were fighting for,” Sian said in the panel discussion at the film rescreening. “The communities can speak for themselves through these films, Where communities know what is needed, Where communities really understand what the bottom line is.”

Women like Sain played a vital role during this dispute. She was one of many women who joined miners’ strike support groups in South Wales. She helped organise kitchens and aid networks that kept families going for months without income.

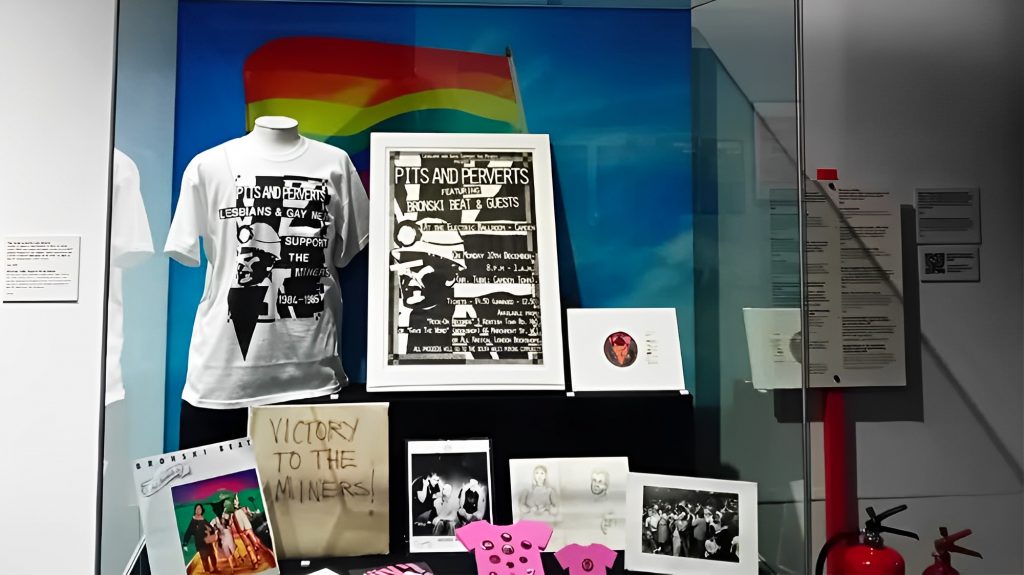

Solidarity came from beyond the valleys too. Groups like Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) raised funds and stood in solidarity with communities that had long been marginalised.

Sian firmly stresses this movement of solidarity changed people, including herself. It opened up space for conversations about justice, identity, and shared resistance.

Despite it ultimately ending in the miners’ defeat, its legacy echoes across many movements and perspectives in the UK.

“I was learning as much from them as they were ever learning from me,” she says. “They are wonderful people, they understood what oppression all was about.”

For Terencn personally, he chooses to answer this question with a quote from an elderly man he interviewed in his second film.

“The big lesson of these days in the mineral strike is the power to say no,” Terence says. “And that’s what the miners did, even when it cost them everything.”