As Welsh museums face pressure to decolonise, how can coal heritage sites honour local history while confronting the injustices of the past?

“Now, I will turn off the last lamp. Put your hand in front of you, about five centimetres away.” In seconds, my hand vanished into the pitch-black void. The only sensations were the howling wind in the tunnels and the uneasy murmurs of the tour group.

“That was the everyday life for a five-year-old boy working underground,” said Adrian, the guide. “The only sound he lived for was the horses pulling coal carts.”

This is the Job a Knock tour at the Big Pit Museum, a journey that takes visitors 300 feet underground. The site, once a fully operational coal mine, employed over 1,300 workers at its peak in the early 20th century. Today, it serves as a heritage site, preserving the lives of Welsh miners.

Tourists will wear miners’ helmets, waist bags, and gas masks before stepping into the cramped lift that once carried over 30 miners at a time. Among us were sixteen students from Lyon, France, on a field trip led by their teacher. As the cage rattled downward, the nervous tourists began singing “Au Revoir” to steady their nerves.

“We can’t imagine what miners’ life looked like until we saw this,” said Anaïs, one of the French students. “There is a similar coal museum near Lyon, and now we are visiting the British version.”

Above ground, the museum’s King Coal exhibition brings history to life. After a “bomb” sound, people standing in the dark tunnel all stepped back and had no clues about what was happening. Suddenly, a giant metal spider came out of the cave, it is a rotary drill used to cut through the coal. As the miner explained, we learned how the mine is excavated, and how coal is extracted and transported.

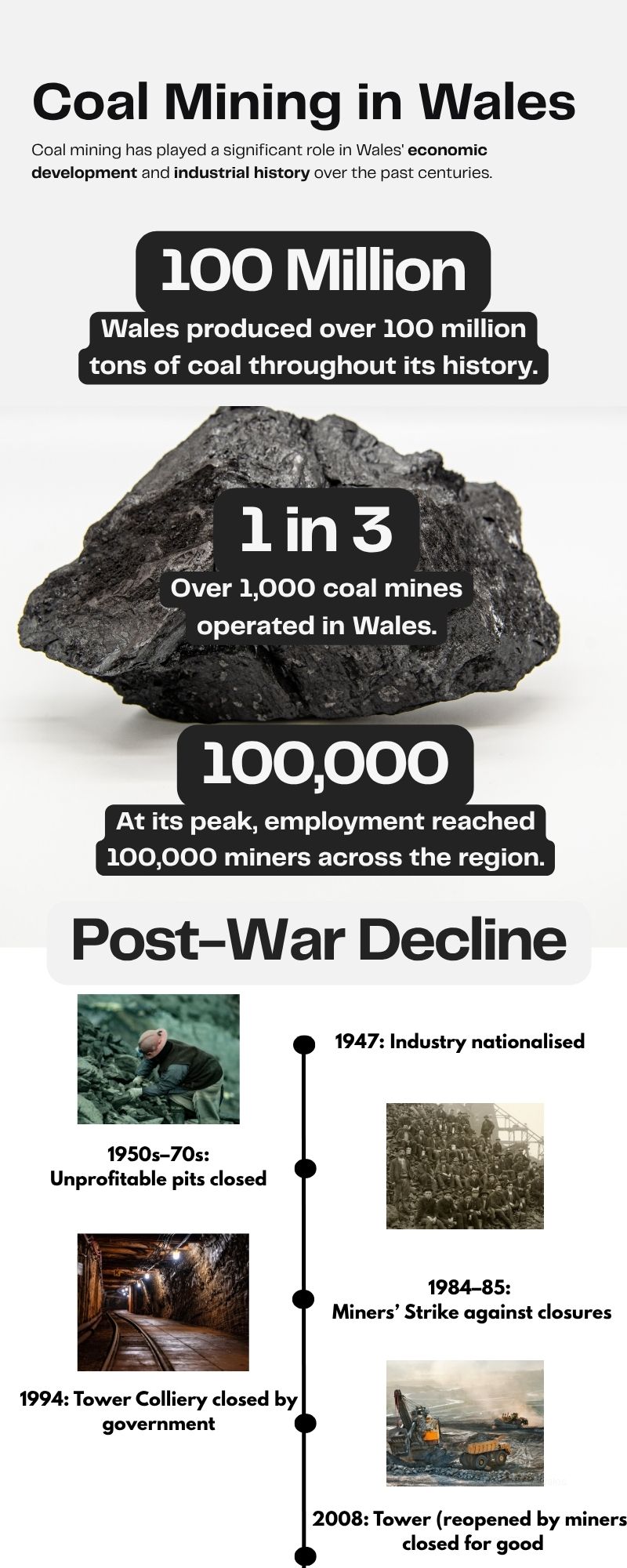

The exhibition traces the development of coal mining, which accounted for more than 25% of Britain’s energy supply during the 19th and early 20th centuries. However, beyond recounting the industrial past, the museum is now tasked with addressing mining history through a global and post-colonial perspective.

“We have to rethink how we’ve told our stories and explore different perspectives,” said Kathryn Jenkins, the museum’s communications manager. “But there’s little guidance or support on how to do this.”

Among all the exhibition rooms, the Bath House is the only space where miners could relax and socialize. On the wall near the exit, a large poster shows the coal industry’s impact on Wales: “The coal industry linked Wales and the rest of the world through people, trade, and industry.” While this was written before the decolonization mandate, the museum now needs to add more to it.

The Welsh government’s initiative to decolonize museum narratives by reassessing the impacts of British industrial expansion, which relied heavily on international labor and resources. However, while the directive is clear, execution remains a challenge.

The museum is collaborating with Filipina-Pakistani artist Sadia Hameed to bridge the gap. Her upcoming exhibition will focus on the international solidarity among miners. “I’ve been looking at moments in Welsh mining history where solidarity extended to other parts of the world,” said Sadia.

However, finding documentation and supporting facts on these global connections is challenging. “A lot of this history isn’t in archives”, Sadia said. “Some critics argue that this is rewriting the history and is politically driven, but this is not about erasing history. It’s about adding missing things. We’re not taking anything away from existing displays but filling in the gaps with stories that were hidden.”

Prior to implementing an apropriate decolonial narrative, Big Pit has actively worked to reveal hidden histories through a feminist lens.

Mining has always been seen as men’s work, but the exhibition following the Bath House uncovers the role of women. The gallery, designed to feel like the modest home of a miner’s family, displays photos of miners’ families and a recreation of their living spaces. The room is small and furnished only with essentials: a wooden chair, a simple bed, and a table with a single Bible, the only book most miners read. Though there was little to clean, miners’ wives faced the challenge of keeping their families healthy in harsh conditions.

Before pithead baths, miners returned home covered in coal dust, which their wives had to wash off using heated water. The dust settled everywhere, coating furniture, bedding, and even food, making it nearly impossible to keep the home clean. Long-term exposure led to illnesses like pneumonia and lung disease. Over time, women and social reformers pushed for pithead baths, successfully convincing mine owners and the government that the baths is needed.

After leaving the gallery, visitors reach the highest point of the site, offering a birdview of the historic mining heritage. At the top of the steel frame, the Welsh flag waves in the wind. As we made our way down, we encountered visitors from India and France.

“I have been exploring different periods in Welsh mining history where miners showed international solidarity, making these stories more relatable to people around the world,“ said Sadia. “For example, I’m also working on several sculptural pieces featuring tin can telephones that children play with. Each pair of tin cans will commemorate a Welsh mining strike while connecting to designs honoring ongoing mining strikes in places like the Philippines, Indonesia, and South America.”

During the 1984-85 UK miners’ strike, Ukrainian miners raised money for Welsh miners. Similarly, South African and Spanish miners sent financial aid and supplies.

Beyond financial support, miners’ unions also formed international networks. The National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) frequently exchanged strategies with labor movements in Poland and Russia during the 20th century.

With the Big Pit Museum stepping into this evolving narrative, the Welsh Government faces pushback in its strategy of showing historical injustice in museums.

Andrew RT Davies, the leader of the Welsh Conservatives, criticised the attempt to mandate a version of history, said, “Our Welsh heritage doesn’t need to be decolonised to appease the wholly woke Labour Welsh Government.”

The museum was set up with the aim to preserve the mining history of Wales. In light of the ongoing debate, the challenges faced by the management team has increased exponentially.

“There are two things that will never be forgotten in Big Pit. One is memory, this museum preserves every detail in Welsh miners’ lives. Another one is pride, miners and their families are always proud of their heritage and the sacrifices made to fuel a nation.” said the guide Adrian at the end of the tour.