The Welsh national team offer a bone crunching form of rugby that makes it the preserve of young, gifted players. But Wales’ newest walking rugby team in Torfaen is aspiring to open the sport to everyone, all in the name of their former beloved player.

Within the first five minutes of catching the pass, though he was smiling, the late 78-year-old Henry Swift lost all of his colour.

“We thought we’d killed him,” recalls Kerry Phillips, one of Swift’s first teammates on the then-Torfaen Dragons.

Phillips now plays for the Torfaen Swifts, Wales’ newest walking rugby club launching in April. Focused on spreading the sport’s mental and physical benefits epitomised by their late teammate, the re-name is part of Swift’s enduring, albeit unexpected, legacy.

It was at that Saturday morning practice over a year ago that Phillips led Swift to the sidelines. He offered him some water, sat with him for a moment, and as the colour returned, he watched Swift eventually return to the pitch and play three or four five-minute bursts over the remaining hour.

“Bursts might be overblowing it,” says Phillips with a smile. But any more physical exertion seemed improbable. Swift had a temperamental heart, declining mental health and hardly the stamina or build of a Six Nations athlete. As the team’s first game approached, Swift made it clear he wouldn’t be attending.

Swift never explained why, though it became clear a calendar conflict was far from the reason.

“It was that he didn’t have the confidence yet to come out with us,” Phillips says.

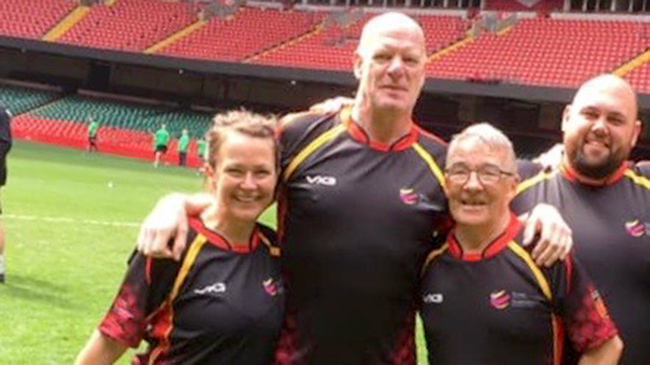

Yet six Saturdays later, Swift still walked the pitch, maintaining his colour (and smile) well into the full hour. When the first game arrived, Swift played. Then, as if that weren’t enough, Swift trumped that by playing again in the Millennium Stadium weeks later.

“It was something he’d never imagined he’d be able to do,” says 59-year-old Gareth Baldwin, another former teammate. “To play, let alone step on the hallowed turf and meet his heroes. For Henry, it was [the] pinnacle.”

Swift represents one of many men and women in Wales to find physical and mental refuge in the emerging craze of walking sports.

In the last 18 months, rugby’s gentler walking cousin has particularly mushroomed in Wales, blossoming from a meagre two clubs into nearly 20. Each week, over 300 players in Wales varying in size, age and gender lace up their boots and play a sport infamous for its physicality without fear of being bulldozed by someone triple their size.

“I mean, would you play on a field if I could run straight through you?” laughs Phillips, whose 6-foot-3-inch stocky frame towers over most of his teammates.

Walking rugby inevitably raises some dubious eyebrows. Played on a quarter of a typical pitch, running is forbidden, as are rucks, high tackles, traditional scrums and (really) any physical contact of any kind.

“I think sometimes with ‘walking’, people think it’s a little stroll, look at the daffodils, but it’s not,” says Dr. Jane Dorrian, the team’s leading and only lady.

Yet walking is precisely what makes a sport generally tagged as only for those handsomely touting calf muscles bearing on Dwayne the Rock Johnson available to everyone.

“It’s for everyone,” says Baldwin. “Wherever you are in the scheme of things, whatever size you are, whether you do marathons –”

“—or you do Snickers,” says Phillips, patting his belly.

“It’s every walk of life. As long as you can walk, you can play,” says Baldwin.

His wordplay isn’t so much tongue-in-cheek as it is succinct summary, specifically for the Swifts. Some clubs form for former international players, others for seniors needing to reach daily step counts.

The Swift’s roster stubbornly boasts a bit of it all, reading more like an indiscriminate drama casting:

Cancer and heart attack survivors mingle with players with knee injuries and blood diseases. University superstars with amateurs who’ve only seen the game from sofa cushions.

“Sometimes we look like a mummy convention,” Phillips says.

“Especially when we’re all taped up with big knee bandages,” Baldwin says.

Six-foot men, a five-foot woman, 20-year-olds, 60-year-olds — all a happily mottled mix.

“People have definitely asked what we are,” Dorian admits. “I’m like, obviously,” she flashes an equally genial and fierce grin, “we’re playing rugby.”

Despite what it’s name suggests, the sport is a far cry from some laissez-faire substitute for the older and out of breath, and the physical elements aren’t lost in gentle traipsing.

“I’ve made the mistake, I’ve dropped my shoulder to go into a touch and the guy’s going, ‘I’m 76 years old, my friend. I’ve got a pacemaker,’” says Phillips.

But the chances of players getting visibly angry are rare. There’s easy banter, the occasional friendly backside smack. Then the emphasis always returns, at every stage, to inclusive non-competitiveness.

“It’s a non-contact sport at heart. It’s all about enjoyment,” says Baldwin.

Walking rugby provides those who thought they never could before or ever could again the chance to do just that. It’s what Phillips can only describe as a return to the ‘instinctive rugby grrr’, that childhood thrill of catching your first pass or throwing a ball where it was meant to go and knowing you meant it to go there.

“It’s that thrill, ‘I did that’,” he says, only this time the thrills comes with a polite, swift tap rather than a potential pummel.

Since Swift’s passing in February, the Swifts have adamantly worked to spread that ‘grrr’ confidence to as many as possible, regardless of background, ability, age or gender.

“I think everyone has a story about how they arrived here, but no two stories are the same,” says Dorian. “We’ve all got to that end point.”

Yet the team doesn’t feel so much like an endpoint as it does a second lease of life.

For Dorian, glory days on the pitch turned to cooking hotdogs for her son’s team two years ago. Baldwin’s rugby love-affair ended 15 years ago as his daughter and long-time passing pal went to university. Phillips went from a 20-plus-year competitive career to shutting himself off after job-related health issues.

“I was getting scared to go out, getting anxiety to leave the house,” he says. “It’s that social element that I thought I’d replaced but obviously hadn’t.”

Its why Dorian and Baldwin are teaming with local GPs and initiatives like Better Man and If You Go i Go to make the Swifts not only a sports club, but a go-to social prescription. The sport keeps its players physically healthy, the team keeps players vitally and happily returning.

“If you’re sat there in the one room with all the thoughts going around in your mind, that’s all that happens to you,” Baldwin says.

“When you get out, it doesn’t matter where you are, but that you get out,” he says. “You’re with a group of people you can interact with, rather than getting deeper and deeper into negative thinking.”

“By the time you do, you’ve dropped the ball and it’s all gone wrong,” Dorian says.

If you do drop the ball, it’s a matter of picking it up. The sport is all about chances: a second chance at the pitch, a third chance at a try, a once in a lifetime chance to play in a national stadium cheered on by none other than your heroes.

It’s why hashtags like #PassingItNotPastIt and #WalkOn have become Twitter mantras, why tournaments are instead gleefully dubbed ‘festivals.’

Winning or step counters come second.

“It’s that idea, while I can I should,” says Baldwin. “Because a time will come when I can’t.”

Swift’s time came some weeks after the game in the Millennium Stadium, after he and his teammates vied for the pegs of their favourite rugby heroes and passed beneath the official player’s entrance like official players.

“We watched him get physically healthier through this team,” says Phillips.

“He was our mascot,” adds Baldwin.

So as the team looked to launch a new, independent club this year, the decision to re-brand ‘The Swifts’ wasn’t just unanimous – it was obvious.

“It’s given such a positive start to the new era,” says Dorian. “Everyone can get behind the name, what it means, how it encapsulates who we are and where we want to go, whether they knew him or not.”

The Swifts aren’t fast, they’re swift walkers. They play the game in a swift manner. And while they might not resemble J.P.R. or Phil Steele in physique or try percentages, they play for Henry Swift’s legacy and will keep doing so for everyone else.