Not a pointy hatted wizard, but an environmentalist? Cardiff researchers offer a surprising new perspective to Merlin

From Disney’s pointy hatted caricature to the BBC’s sleek modernized wizard, Merlin has been reimagined in countless ways throughout popular culture. However, this identity might undergo further change, thanks to a new study by Cardiff researchers.

According to Dr. Llewelyn Hopwood of Cardiff University’s School of Welsh, Merlin can be seen as an ancient environmentalist seeking solace in nature.

“We have found poems where Merlin is taking great pleasure in the vegetation and the animals around him,” said Hopwood. “The bond that he cherishes with nature, and the sympathy that he has for it, definitely makes him one of the earliest environmentalists known to us.”

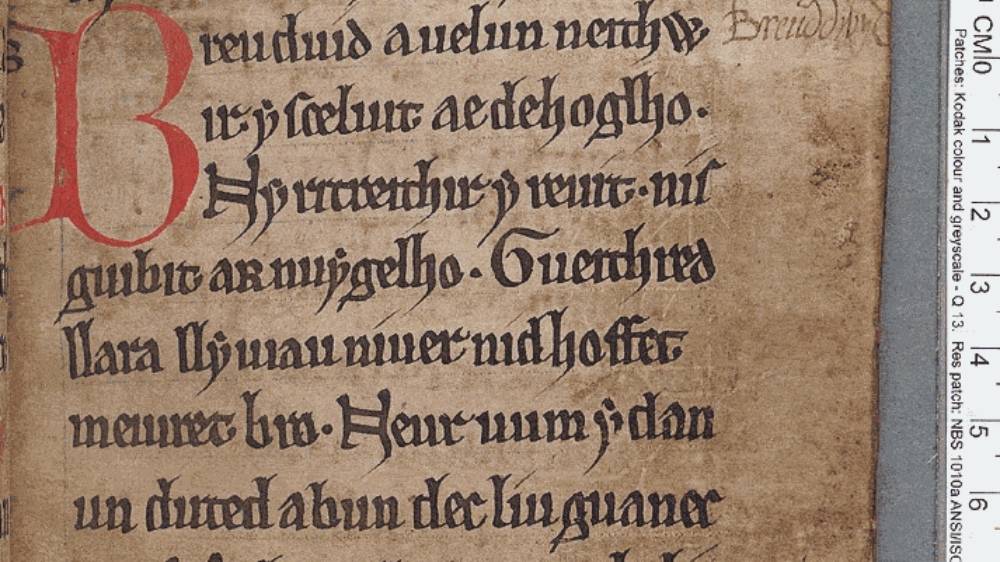

Merlin’s legend is a major part of Welsh and British heritage, yet much of it remains shrouded in mystery. Over the past three years, researchers have painstakingly re-examined medieval texts as part of the Myrddin Poetry Project.

This collaborative effort led by Cardiff University, Swansea University, and the University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies aims to uncover the Welsh interpretations of Merlin, separate from later European adaptations. The Cardiff team, led by Dr. David Collander, includes Dr. Hopwood as a key researcher.

“Most modern interpretations of Merlin stem from the works of Geoffrey of Monmouth,” said Hopwood. “This version cemented Merlin as a stargazer, a magician performing grand tricks, and eventually, a silly wizard in a purple hat. But the original Welsh Merlin was something else entirely.”

To challenge the “Disneyfied” image of Merlin, researchers have analyzed 519 medieval Welsh poems, translating and editing 4,450 lines across 102 of them. Their findings are available on the Myrddin Poetry Project website (www.merlinpoetry.wales), which is currently in beta format and will be fully operational by the end of 2025.

There are two poems that specifically highlight the naturalist persona of Merlin. The 12th-century poem Yr Oianau or Merlin’s Woes is edited by Hopwood himself, and the second one—Yr Afallanneau or The Apple Tree from the same era is edited by Ben Guy.

“Merlin’s Woes is quite a melancholic poem, in which he bemoans the state of the world and presents himself as a cold, dying man,” said Hopwood. “But the one thing in which he finds solace is his natural surroundings.”

In this 200-line poem, we find Merlin praising the birds, cherishing the visions of the stags, and thanking his wolf and dog companions. However, the most striking feature of the poem is Merlin’s fascination with a little piglet, whom he considers his friend.

In the poem, there are instances where Merlin is worried about his little friend: “Och, little piglet, oh little white sow, do not sleep a morning sleep, do not dig in the woods in case Rhydderch Hael [a king and Merlin’s foe] comes with his trained hounds.”

“Most of the visions and prophecies that Merlin delivers in this poem are bleak, mostly about the imminent defeat of the Britons,” said Hopwood. “Yet, he takes great pleasure in the companionship of this small creature.”

Just like the piglet, Merlin also feels deeply for an apple tree as well. In the poem Yr Afallanneau, we find him telling the tree:“Myself, I am fearful, anxious about you, lest the woodmen should come, forest-hewing, to dig your roots and pollute your seed so that an apple might never grow on you again.”

“The apple tree, in this case, serves a metaphor,” said Hopwood. “It represents a microcosm of the greater world, warning of greater environmental disasters.”

Hopwood even suggests that Merlin’s lament could be interpreted as an early prophecy of climate change: “Merlin, in a way, prophesized the climate emergency,signaling the dangers of deforestation and ecological harm through his grief for the apple tree.”

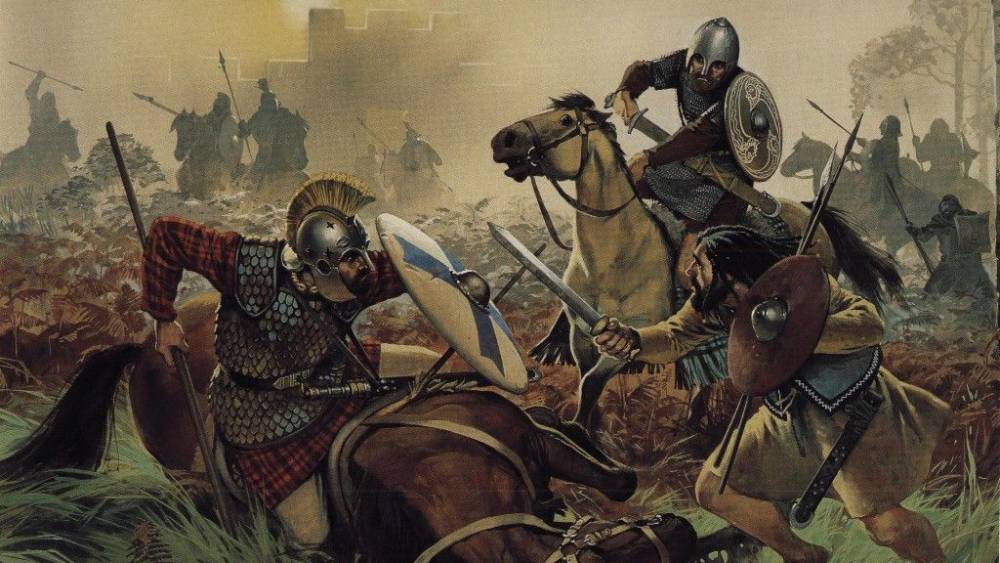

According to legend, Merlin took refuge in the forest after the Battle of Arfderydd in 547 A.D., after suffering from a condition like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). While in the forest, he recovers emotionally and develops his prophetic abilities.

According to Hopwood, this episode highlights the soothing impact that nature has on a person.

“The Merlin poems don’t say anything about the battle but focus on his transformation afterward,” said Hopwood. “There is no shadow of a doubt that the ancients already understood that nature has a profound ability to heal trauma. Modern research should explore it furthur.”

Speaking of why it took so long to rediscover Merlin the Environmentalist, Hopwood said the legendary figure was a 6th-century nobleman from the Old North, the region comprising southern Scotland and northern England and spoke an ancient variant of the modern Welsh language. And in the earliest traditions, Merlin was also not associated with another legendary figure—King Arthur.

It was Geoffrey of Monmouth, a clergyman, who brought these two distinct figures together around the 12th century. The medieval romance poems of the Arthur-Merlin duo soon took Western Europe by storm, and the original Welsh interpretations were lost in time.

“Merlin has been many things to many people over the centuries,” said Hopwood. “But at his core, he was someone who found meaning in nature. That’s the version of Merlin we see in these poems— not a wizard casting spells, but a man who understood the world through the trees, the animals, and the land around him.”