As it goes, behind every great man is a woman, and behind this man’s shrine is another. But who is she and why, after 11 years, does she still care for a shrine of a man who never technically existed?

Carol-Anne Hillman has a method.

She leaves the left corner for flowers, the top for bunting. The middle posts she laces with silk roses, four bunches strewn with coordinating red tape while the rest hang in pairs upside down as Valentines Day calls for this time of fandangle. Then she re-weaves the suit ties: two maroon, two a brighter rouge, synching the last knot with a rote tug.

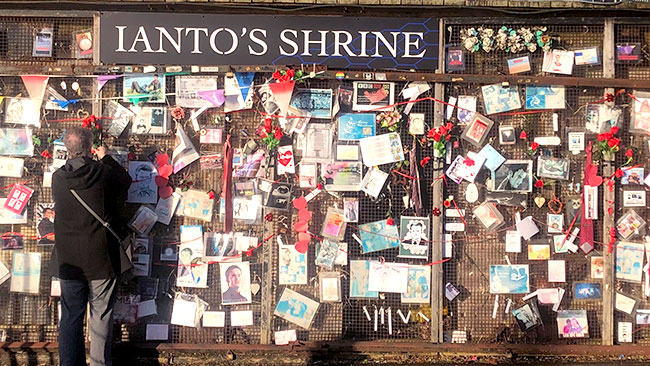

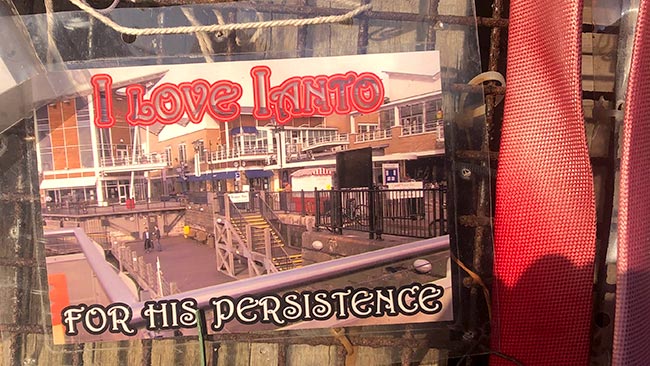

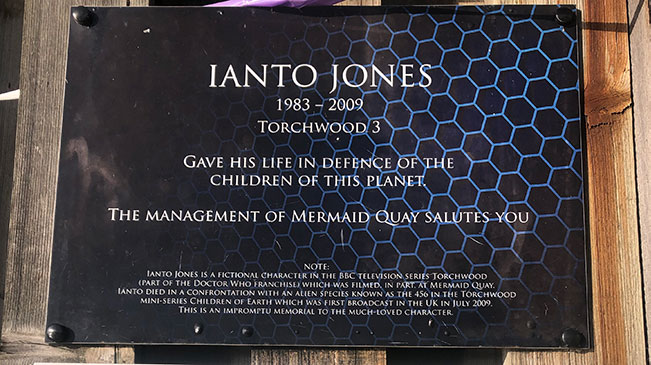

“He always wore a nice suit,” explains the 68-year-old official caretaker of Cardiff Bay’s Ianto Jones shrine, an impromptu memorial erected in 2009 for the BBC Torchwood teaboy who died unexpectedly at the hands of the script writers.

Since 2014, Carol-Anne Hillman has spent her days looking after this otherwise wont wood panelling nestled at the bottom of Mermaid Quay. She sifts through tributes sent to her Roath home from fans all over the world, primes their locations on the wall, removes tarnished items and guarantees each holiday is suitably feted.

This morning she’s making her usual rounds, mentally orchestrating her upcoming plans: 32 multi-coloured chicks for Easter, plaited leis for Spring, daffodils for St. David’s Day. All year she keeps the love locks, the plastic coffee mugs, laminated poems, drawings and letters sent from as far away as Mexico. Today, she has a newcomer: a palm-sized macramé quilt of two men holding hands.

“They’ve put that up there since I left yesterday,” she says. She leans forward, squints her eyes and promptly adjusts the scrim away from the photograph beside it. It’s of a man, brown-haired and doe-eyed boasting a dark horse smoulder. It’s the same man beaming from the shrine’s every angle.

“He’s handsome, huh?” Carol-Anne sighs, not waiting for an answer. “He’s got more handsome, like a fine wine.”

For a Torchwood fan, it’s a dream come true: 24/7 Ianto Jones.

“A lot of people say they don’t understand it,” Carol-Anne says. “But I’ve got no husband, no kids, no worries.” She cocks her head to the side one last time as her hazel eyes zero in on her latest adjustment. She makes a final tweak before vaunting an insouciant shrug. “To each to their own.”

It’s a simple response, but if Carol-Anne is simply anything, she’s simply a fan.

She’s written over 200 fan fictions, her first just six days after the character’s death and spanning 150 pages. Every episode has been watched, every book/audio tape bought. She knows what colour tie suits Ianto best (blood-red), waistcoat suits him worst (none) and can recognise Ianto’s actor Gareth David-Lloyd by nothing more than the area between the middle of his nose and top of his mouth.

“I would know it was him from 100 yards away,” she says. “You never forget the mouth. In every picture I’ve got on my wall, because I’ve got loads, you can see the mouth.”

Twenty-two hang in the bedroom, alternating from shots of her and Gareth together to individual shots of the actor himself. Twenty-two more hang in the front room, the hallway’s horde is immeasurable, and though none hang in the spare bedroom or toilet, it’s not out of the question.

“When I say to him, ‘Can I have a picture taken with you?’ and he shouts, ‘Haven’t you got enough?’, I say no, I still have room in the toilet,” she says with a cheeky grin.

This perhaps is the most salient contrast to any other makeshift shrine around the world: Most caretakers don’t become friends with their enshrined. Most of them can’t.

“You could say it’s weird,” Carol-Anne deadpans. “But see, I wouldn’t try to take [Gareth] off his wife. Ianto I would try to take off of Jack.” Carol-Anne pauses before her steel chaff cracks. “I’m in love with a fictional character,” she confesses. “But Gareth, he’ll do fine.”

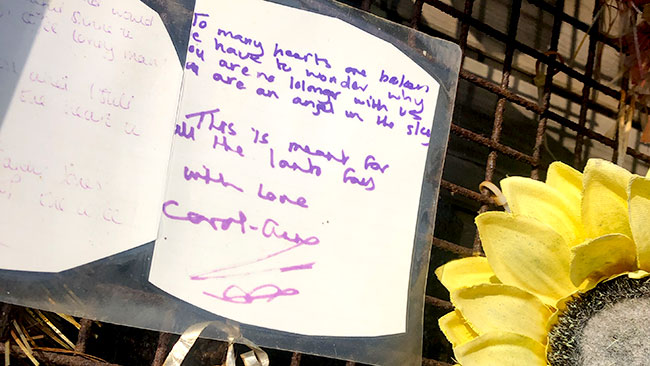

An early letter from Carol-Anne still hangs in the left corner.

While their initial 2009 meeting demanded a coaxing shove and a heartbeat verging on heart attack, Carol-Anne has surpassed the standard barrier between fan and fan-ee.

She calls him Gareth, he calls her Ol’ Woman. When she dressed up as him for Comic Con in 2011, she sported his very own shirt and trousers. Once she convinced his heavy metal rock band, Blue Gillespie, to play in a cramped pub in her hometown, Ash, Surrey, where she bobbed her violet-streaked pixie cut so fervidly, she felt sore for days.

“I followed that band for months. I followed them to Cardiff,” she says.

Carol-Anne knows his wife, she’s played with his kids. At his plays, Gareth introduces her as a friend of the family. He owns a copy of her first fanfiction, and she adopted one of his cat’s kittens — which she named Max, not Ianto.

Carol-Anne and Gareth at a comic-con convention.

Carol-Anne and Gareth have been friends since 2009.

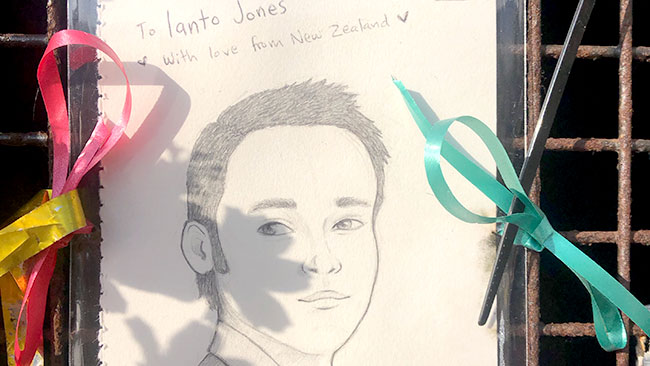

Drawings are sent from New Zealand.

A couple visited on their wedding day.

On the surface, Carol-Anne comes off as just another fan, albeit a slightly more infatuated one and, in spurts, even exuding a doting grandmother aura as she skims through her phone’s trove of Gareth photos with deft memory.

“See how he’s wearing shorts?” She stops on a photo from the Shrine’s 10th anniversary last summer. “He cycled two and a half hours to get here. And there’s his beard. I quite liked him with his beard.”

Yet beneath that adulating veneer, Carol-Anne pushes much deeper than sepulchred phone photos.

For five years, Carol-Anne has been something akin to a one-woman defibrillator to a shrine left to rot, and perhaps the most inauspicious of them all.

Four days before he died, Carol-Anne didn’t know what Torchwood was. Her mother’s passing led her to move in with her brother, where the sibling unexpectedly declared they’d watch the five-day marathon of season three. In three days, Carol-Anne fell in love. In four, her heart snapped.

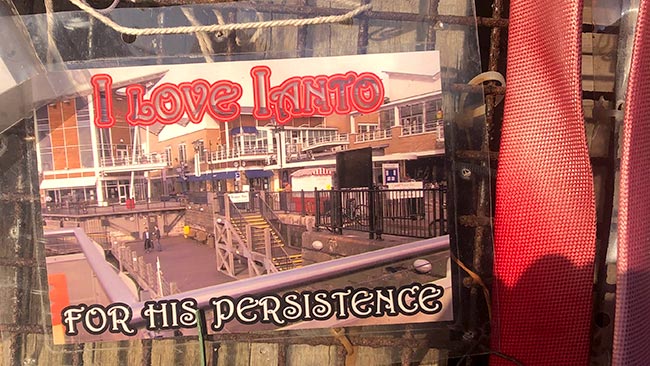

For Torchwood fans, Ianto Jones was tantamount to a well-tailored revolutionary. One of television’s first LBGTQ characters to headline a series, he was quirky, jest-ready and smiled like a satisfied panther. His death consequently spawned a virtual dirge, from a mounting campaign to bombard the producers with tea to the innocuous lily bouquet that bloomed into the 20-foot-long shrine Carol-Anne polishes now.

A week later, Carol-Anne travelled three hours to slip around a barricade and pin her hand-written poem to the fledgling beginnings of this shrine. One would assume Ianto’s voice sailed the wind in this moment, imploring Carole-Anne to stay, like her very own Field of Dreams moment. But Carol-Anne pinned the tributes and left.

The Ianto Jones plaque hangs beside the wall, to let bemused passersby know that the shrine is very much for a fictional man who has not faltered in adoration.

She wouldn’t return to Cardiff for five years, happening to follow Blue Gillespie. By then, the shrine had waned into disarray: rain-smeared poems, sun-faded photos, tattered signs from errant stag-dos, all culminating in a maroon thong and a pair of yellowed pants flapping in the breeze like derelict battle flags.

“You don’t put up a pair of dirty pants, good grief,” Carol-Anne says with a roll of her eyes.

The shrine could’ve evanesced with the pants’ inevitable yellowing had Carol-Anne been any other woman and Ianto Jones any other character.

“Ianto loved more than anyone could love. That’s who Ianto is,” she says. “He’s the kind of character who snags your heart.”

So as Carol-Anne found herself vis-a-vis an unsaturated shamble of the shrine’s former glory, she thought only one thing:

“I had to do something. Even Gareth said, ‘Carol-Anne, it’s gone grotty.’”

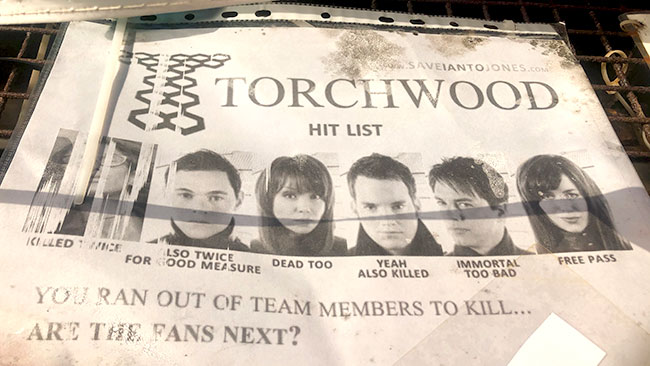

Of course early days didn’t see only roses. Storms brought floods. Conservatives complained of the wall’s pro-LGBT stance. Fans carped that Carol-Anne had no right to remove illegible tributes, even accusing her of stealing a ceramic mug.

“It nearly turned into World War III. That’s when I that’s it then, I’m not going to do this anymore,” she recalls.

But then came Gareth, who told the fan it was him.

“Of course it wasn’t. It’s only because I said I wouldn’t do it anymore that he did.” She grins. “We couldn’t have that.”

They can be risky business, impromptu shrines. Sometimes, they transcend. There’s John Lennon’s memorial in Central Park. David Bowie’s mural in Brixton. The hundreds in Los Angeles following Kobe Bryant’s recent passing.

Despite the show quitting on Ianto, Carol-Anne won’t follow suit anytime soon. Her Twitter following has swelled to 480 in just six years. Fans have donated £90 for Christmas decorations. Not a pair of pants is in sight.

As for the shrine’s future, Carol-Anne isn’t really that concerned.

“I’m 68 now, I’ve got another 20-30 years of doing this hopefully. I should be on a motor scooter then, but I can get to it, go down the ramp,” she says.

And if people stop sending tributes?

She winks. “Me and my friend have printers.”