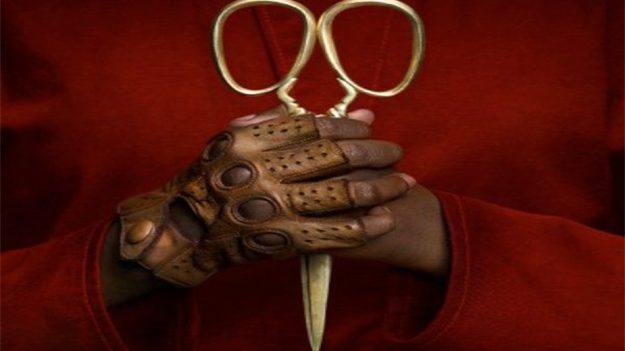

Jordan Peele’s follow–up to cultural phenomenon Get Out uses the horror genre to put America under the microscope. What conclusions does it draw?

Given how comedian Jordan Peele reinvented his image with the acclaimed social-horror thriller Get Out, inventing new cultural shorthands for the experience of black Americans (the unforgettable “sunken place”) and garnering himself a Best Original Screenplay Oscar in the process, expectations were very high for his sophomore feature Us.

Another film promising to exploit the potential of the horror genre to examine social issues (the title can be read multiple ways), the bar that Us had to clear in accomplishing the same level of cultural relevance and cementing Peele as a new auteur was very high.

The film opens with a haunting and beautifully shot prologue set in 1986, in which a family visit a nighttime beach carnival. While her father is distracted, the daughter, Adelaide, wanders off on her own and enters an empty Hall of Mirrors attraction. There, she encounters something horrifying.

Cut to the present day, in which Adelaide (now played by Lupita Nyong’o) is vacationing with her husband Gabe (Winston Duke) and two children at their summer home. While the family seems to have a well-functioning relationship, there is an underlying tension: they are near the beach where the traumatic event occurred, something she has never discussed with anyone.

Soon after, strange coincidences and disturbing images begin to pile up, culminating in the appearance of a strange family in their driveway.

On first viewing, Us may seem a messier, less well-honed effort than Get Out was, in the manner of many second features. It has a more expansive feel, and its subtext is not as easy to decipher.

Get Out’s central metaphor made explicit the effects of subtle, toxic forms of racism camouflaged under a patronising liberal veneer.

Us clearly invites similar levels of scrutiny: “We’re Americans” goes one key line. Like Get Out, when the central threat is explained, it turns out to be based on a high-concept idea that is clearly intended to be read as allegory.

However, the allegory seems to represent a more abstract, universal form of horror than that of Get Out.

The film, on some level, is about the uneasiness of living a comfortable life, despite, or perhaps because of, the suffering of those with less.

Particularly revealing might be the portrayal of the central family’s relationship with another more affluent, white family. Gabe’s efforts to compete with his friend’s signs of wealth are portrayed in a light-hearted fashion; however, in retrospect they take on a different register, as the chasms between social groups are given horrific life.

In fact, many other things take on more significance in retrospect. Only later does it become possible to appreciate how subtly Peele weaves key hints into the narrative, with off-hand comments and visual clues (watch out for 11:11) having more significance than a casual viewer might guess.

There is also a key twist that deepens the issues raised, forcing viewers to reevaluate everything they have seen.

For those not interested in deeper significance, the film works well as a thrill ride, with a strong vein of humour running alongside its well-executed suspense set-pieces. Like Get Out, it’s an accessible film for people with little fondness for horror cinema, even as Peele’s clear affection and respect for the genre emanates from every frame.

The performances are uniformly strong, with Nyong’o given a welcome opportunity to demonstrate her range with two wildly-different roles.

Peele also demonstrates his growing ambition as a filmmaker, with expertly executed instances of cross-cutting towards the end that brilliantly underline the central duality at the heart of the film.

Perhaps most crucially, it is a film that lingers, and that will surely inspire many conversations about its deeper meanings and symbolism among filmgoers with a passion for mainstream cinema with some substance.