Intercardiff meets the people working in the Glamorgan Archives where are home to thousands of documents in Welsh history.

Louis Hunt is worried about insects. Ants are a problem, so are dust mites. There are plenty of people who have a problem with creep crawlies, but for Louis the danger is not finding a cockroach in your kitchen but preserving ancient documents of huge value to Welsh history.

Louis is an archivist at the Glamorgan Archive in Cardiff, who is charged with managing historical documents.

“There are two purposes for that. First is…if there are insect infestations in the documents, if we vacuum pack the material and then place it in the freezer, then that will stop the insects from continuing to lay eggs so that means that we can ensure that we can get rid of the insects,” explains an archivist, Louis Hunt.

The Glamorgan Archives has been in this building since 2010 when it was opened in the building. But actually, it has been in existence since 1939 and holds the records about Glamorgan county, Cardiff, Wales, dating from the 12th century to the present day.

“The other reason is that there are some items in our collections that are on nitrate film. The nitrate film needs to be kept cold otherwise if it’s in the wrong temperature can give off nasty gases and catch fire just because of the temperature and the buildup of gases. So it’s really important for us to keep it safe in the freezer.”

Going through three doors, we enter a corridor called the buffer zone between the outside conditions and the inside conditions. “The purpose of this buffer is to reduce fluctuation changes in the temperature and humidity so that things are stored in the right conditions in the strongrooms. Because if it’s too humid in the strongrooms that mods can start to grow. And we thought it would damage the documents if it’s too dry,” says Louis.

On the wall to the right of the buffer zone, there are huge red gas canisters, nearly as tall as a person. These canisters are filled with organic nitrogen that would be used to put out fires in the strongrooms, “Because most of our documents are paper. If you put out a fire with water and there’s lots of paper, the paper’s going to get damaged, so instead, we use gas,” Louis says.

Across the buffer zone, we finally enter to one of the strongrooms where keep the documents. “We’ve got about 17 kilometres of shelving, and not all of that is entirely full at the moment because there is always collecting new collections in all the time,” says Louis, pointing to an empty shelf. Normally, people can’t come into the room. The staffs bring documents out from the strongroom into the search room for people to look.

Most of the documents are stored in the grey boxes. These boxes are made of special cards for storing archives, which acts as an extra layer of protection for the materials. “In that has an alkaline buffer to it. So it reduces the acid content in the paper, which is one of the reasons why paper starts going yellow when it gets sold,”

“Also, these boxes have made specifically to the size and shape that we need. So in here would be a big book, but it fits exactly in the box, whereas these boxes are more just sort of standard size boxes for files and things like that,” says Louis.

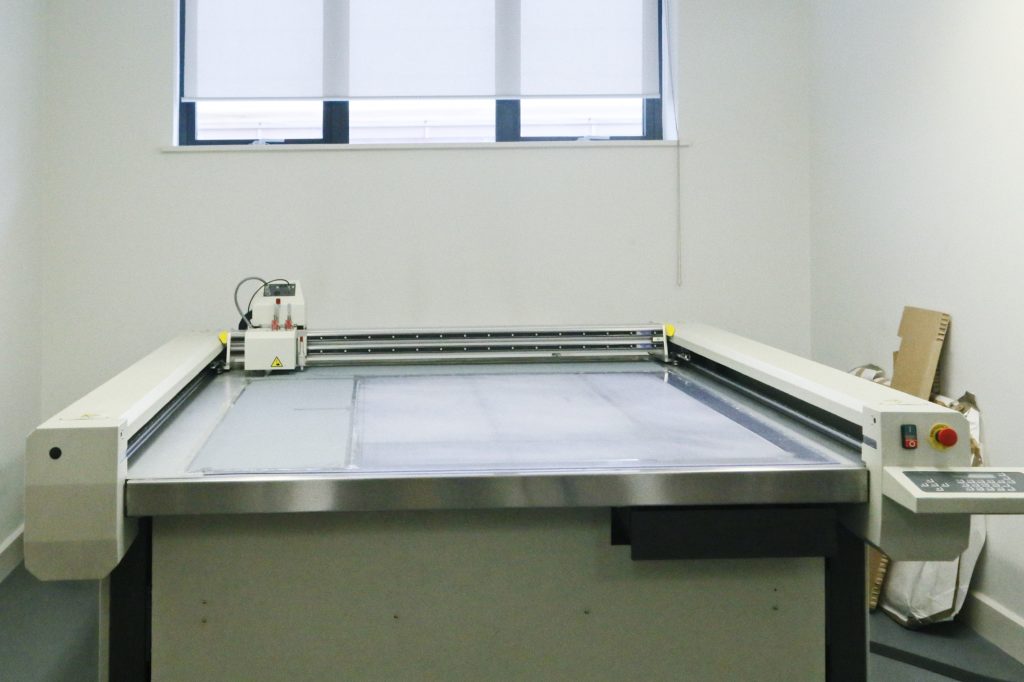

After putting all the records in the boxes safely, some of the files will be given priority to be sent to the repair centre because of their importance, where they will receive the exact treatment that is carried out by the conservation studio.

At the moment, the studio is repairing a map in 1815, point nine meters by two-point seven meters big. It is divided into 22 pieces and put up on the board, which helps conservators to see where repairs need to be carried out.

Lydia Stirling is one of the conservators. She is doing the final work for the restoration of the map. “We used much sponge and washed it, took it apart and washed it in water because it was very discoloured,”

“We have spent forty hours fixing the map; the colours have survived very well. Coming done tomorrow…,” Lydia continues to repair as she speaks.

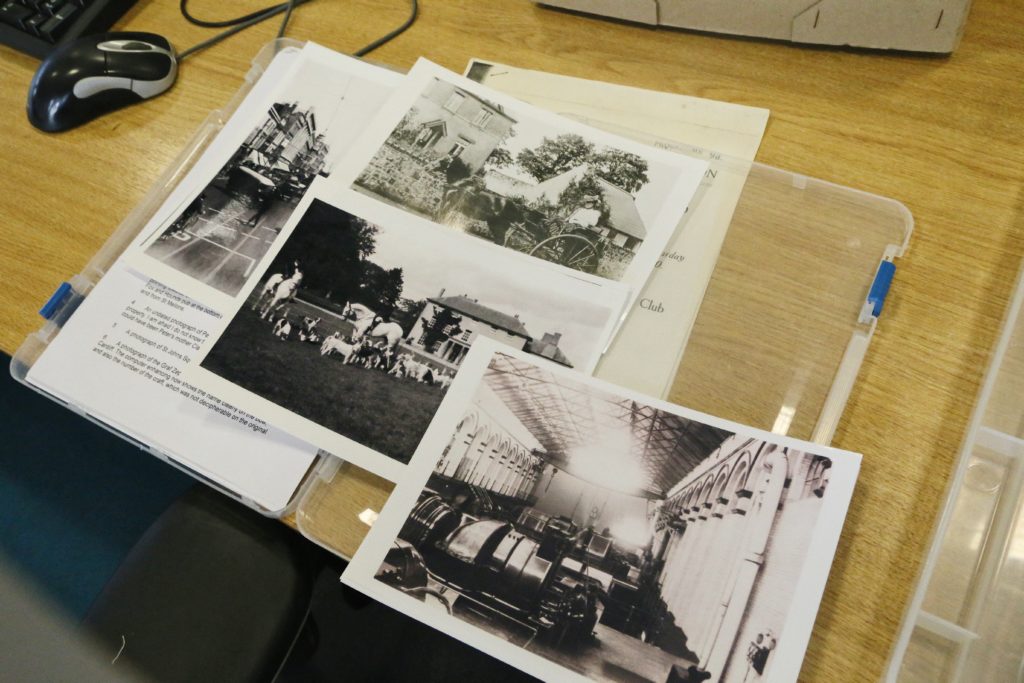

Alice Peters became a volunteer of the archives few month ago, doing research about holocaust, “People don’t necessarily know what happens to them after the holocaust. So i thought to find out what happened so that the synagogue like to know what happened to his family members,” She just finished her work today.

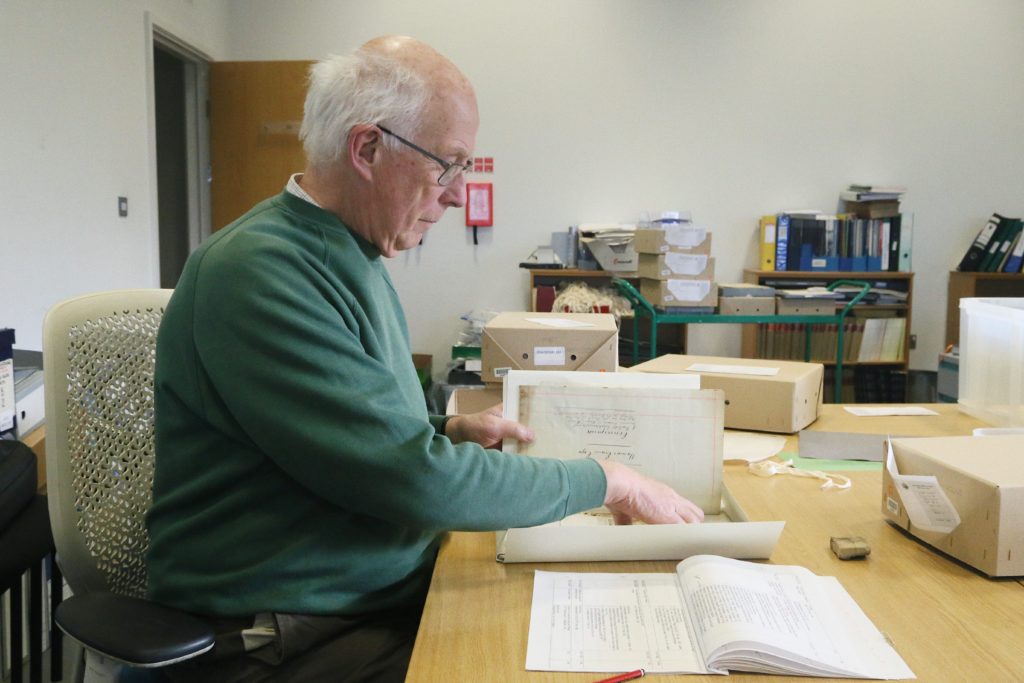

The longest-standing volunteer, Keith Edwards, says: “I hope it will be of interest to people in the future. Looking into their history of the town or their family or where they live so they can know what it was like in the past and to understand how it came to be like,” as he put an old photo in a collection box.