Emergency departments around the world face massive attendance drops as non-Covid patients feel too scared and guilty to seek help. But is avoidance only making an inevitable return worse?

Nearly 20 hours after the chef’s knife slipped two inches under my left knuckle, Mary, a nurse at the University Hospital of Wales, is finally stitching my left hand back into a hand.

Nothing phases her. Not the tourniquet I’ve fashioned out of athletic tape and a kitchen rag and not the blood still trickling down my palm as she synchs the third stitch with a tug.

Yet, when I admit I had no intention whatsoever of visiting the hospital until a friend all but tied me into her car, Mary’s fingers quit moving. She tells me that in the previous week her colleagues called dibs on patients sitting in the waiting room like seagulls squabbling over leftover Greggs’ wrappers. Despite it being nearly 2pm today, she has seen less than 10 people.

“When all this is lifted, patients are to going to flood in,” she says. “They’re going to be worse than ever, and we won’t be ready for it.”

Around the world, non-Covid patients are avoiding emergency departments from mounting fears of Covid-19, thus leaving emergency physicians worried of not only an inevitable surge of patients but worsened states of health.

“We’re concerned about a big spike in Covid coinciding in a big spike in non-Covid, very sick people,” says a doctor from the University Hospital of Wales who wishes to remain anonymous. “It’s a worry, but it’s based on instinct more than anything else.”

According to NHS Wales, A&E attendance dropped from 84,143 patients in March 2019 to less than 62,000 in March 2020. A similar reduction rippled through NHS England, from 2.2 million to almost 1.5 million. Emergency visits in the United States are down by about 50%.

In the last month, the UHW saw roughly a quarter of its usual A&E attendance. The trickling numbers, the UHW doctor says, can be parsed in one of two ways.

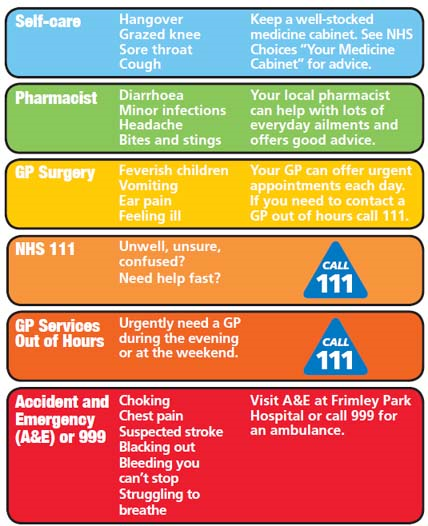

Patients often “chronically abuse” the nature of accident and emergency, a sentiment echoed by many emergency physicians. A&Es are often used for sniffles, prescription refills, grazed knees or two-week tummy aches that called for paracetamol.

“It’s against the code of a physician to turn people away, so we take anybody and anyone who comes. But in doing that, people who actually need help sometimes don’t get the attention they need,” says Charles Mansour, a fourth-year medical student in New Orleans.

In some sense, the dwindling is positive. A&Es no longer face abuse. Increased calls to NHS 111 have re-routed non-emergency medical issues, perhaps for the long run.

But therein lies another problem: Many who don’t know how unwell they actually are are also opting for avoidance.

“We’re seeing things in post-mortems that could be completely avoided with the wonders of modern medicine,” the UHW doctor says. “These people need to present because they need life-saving treatment, and they need it now.”

The major breaking point is knowing into what category each patient falls: the worried well, the slightly worried well, the worried unwell and the not worried unwell — this last group being the most vulnerable.

However, these lines have blurred as many patients fear becoming venal burdens to overworked staff or inadvertently becoming cross-pollinating bees with death wishes.

It’s why 29-year-old Anne Neilson was perrenially apologising to the nurse patrolling the UHW’s front door on Sunday morning, as if she’d personally turned the young nurse’s mother into a toad.

“I felt guilty for using their ‘services’ in a time like this,” says Neilson. Woken up at 4am to massive pressure pushing on her chest, Neilson couldn’t breathe. She was shaking. In any other scenario, a call to 111 would have swiftly followed. Yet, Neilson sat for nearly an hour, debating call or don’t call as if frantically settling love from daisy petals.

“All these calls from people thinking they have symptoms or phantom symptoms,” she says. “People are dying, and well, I’m not.”

Patients’ growing guilt exacerbates what front-line nurse Alyssa Anderson considers hospitals’ current cyclical game of tug of war.

Patients are meant to stay in the ED for four hours, the Texas nurse explains. Problems that occur here propagate throughout hospitals. Done right, hospitals run like smooth flowing dams. Done wrong, the interconnectedness is double-edged. With hospitals’ finite limit of resources, growing Covid-sections bring resource depletions in other areas (i.e. A&Es, CV units). When given reasonably reduced action, those areas can spare them.

But when a large number of seemingly innocuous wounds are left to fester out of fear, things turn septic and the dam cracks. More ambulances are dispatched rather than patients driving themselves. Beds become scarce. Queues grow longer. Add antibiotics, drips, scans, oxygen, maybe ventilation.

“All of these things cost thousands of pounds. More than people would think,” the UHW doctor says. “I guess that’s the major issue for us. The more unwell people are, the more they need. Unfortunately, the more they need, the less likely it is they’ll get better.”

“Even the little bit of pickup we’ve had here and there shows how little we’re ready for a massive surge,” Anderson says.

Global pandemic or not, humans are invariably human. Heart attacks don’t disappear. We use chef’s knives to de-pit avocados. Bones break. That’s our brutally beautiful joie de vivre.

“If anything, it means [going to the ER] is the one thing that shouldn’t change,” Mansour says. “Humans are so afraid of change and things they don’t understand. Right now, we’re living in a grey area and people fear it, but they shouldn’t.

“The ER is essential. Moving forward, this might be good for the emergency community. People might actually use us for emergencies rather than a primary care. But they need to use us now.”