Herd immunity is not the government’s policy, and the UK will be facing a challenging situation as confirmed cases climbing up.

The scientific debate over herd immunity is ramping up after the chief scientific adviser Patrick Vallance said 60% of the population should contract Covid-19 to provide herd immunity.

The official has admitted the failure to contain the outbreak, and announced the shift to mitigating the peak of the illness.

Comparing against the actions taken by other governments, the UK’s approach is not so stringent, and was even described as a gamble by the Financial Times. The timid counter-virus policy, along with the term “herd immunity”, have received doubts and public criticism.

“I couldn’t believe my ears at first when hearing the policy, ” said Dan, a Chinese student studying at the University of Southampton. “I even thought I might die in the UK. I don’t know if the British have any concepts of how harmful and contagious the virus could be.”

But here is the question: Is herd immunity the real case or merely a term exploited by media? Do we genuinely need 60% of the people to get infected? To understand these questions, I spoke with biologists from Cardiff University and worked out the puzzle of herd immunity.

What is herd immunity?

When a certain percentage of the population is immune to a given disease, which is usually through the vaccination, it would be more difficult for the illness to catch susceptible individuals. People who have been vaccinated could form a firebreak for the vulnerable who are not vaccinated. This is called “herd immunity”.

For example, a newborn baby could be protected from measles if he/she is surrounded by people who are vaccinated. Even if the baby is not vaccinated, the likelihood of infection is quite low.

But the issue is, we don’t have a vaccination for Covid-19.

“If in the absence of a vaccine or any other treatment for a disease the only thing that will stop an epidemic is herd immunity, ” said Sarah Perkins, a biologist at Cardiff University. That means people will naturally develop the antibodies to fight against a certain disease. “But it could take in a completely susceptible population. It could take a very long time to get herd immunity,” Sarah added.

.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }Criticism of herd immunity

World Health Organization (WHO) criticised the UK’s policy of relying on herd immunity, insisting the government should take more action.

“if you want over 60% of the population to be infected and become naturally immune that would assume that they don’t die before that. But that makes no biological sense. Because some people will die before they have a chance to become immune to the disease,” said Numair Masud, a PhD student at Cardiff University studying infectious disease.

“So the strategy is very risky and is effectively sacrificing a lot of elderly people and those who are immune-compromised.”

Sarah Perkins said a very limited percentage of the population might have developed the immunity to Covid-19, but it is still far away from reaching herd immunity.

Herd immunity is not the government’s policy

Health Secretary Matt Hancock said in The Telegraph‘s interview that herd immunity is not a part of the government’s strategy. “That is a scientific concept, not a goal or a strategy. Our goal is to protect life from this virus, our strategy is to protect the most vulnerable and protect the NHS through contain, delay, research and mitigate.”

Sarah Perkins said flattening the peak and reaching herd immunity are different concepts. “Herd immunity is being used incorrectly as a term by the general populist and the press,” she said. “I don’t think the government are aiming for 60% of the population to get infected. I think the government plan is to slow this epidemic as much as possible and hope a vaccine or some kind of antiviral will come.”

Reducing contact is the main way to flatten the coronavirus curve. The contact could be classified as direct contacts, such as gathering in a pub or a sports game, and indirect contacts, such as touching the door handle that someone has coughed on.

Boris Johnson has asked the school to close and suggested people working from home and avoid mass gatherings and social avenues. But the question is: Will the policies be strictly carried out and make visible effects?

Anthony Costello, director of the University College London Institute for Global Health, has posted a thread of tweets questioning the policy and calling for voluntary social distancing and lockdown.

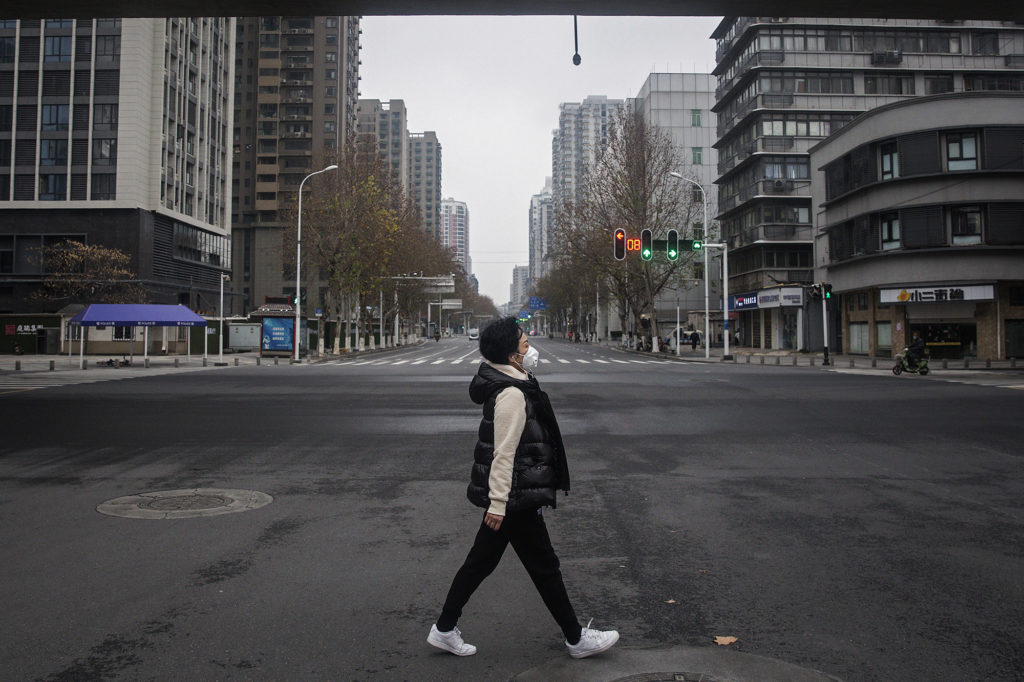

As for performing a stringent policy, China might provide a lesson for that. Today, China has made a milestone today with no local new infections, but it took a seven-week all-out national mobilisation to contain the epidemic: Cities were locked down. Speciality field hospitals were constructed. People did voluntary social distancing under the government’s instruction.

While initially silencing the doctors who alarmed the potential outbreak and mishandling the early containment, the Chinese government took quick steps to cut off the further spread of Covid-19 after realizing its critical impact. The state was transformed into wartime, where the policies carried out under mass top-down supervision.

However, the cost of malfunctioning a large economy is severe. Travel agents grappled with refunds. Gyms and restaurants shut down for no income. Graduates witnessed the diminishing job market. The Chinese economy was slammed with industrial output dropping by 13.5% and the unemployment rate rising to recorded 6.2% according to the National Bureau of Statistics of China.

While the largest epicentre of coronavirus is taking its controlling back, how long will the UK take to contain the epidemic? Is the UK prepared for the difficult issues ahead?