“My life is fairly crazy”: unpaid carers are worried and hopeless for the doubled bills and the closure of services.

Sitting in a small, one-bedroom flat, Sarah was checking the letter she received from the government about allowance as well as looking after her disabled sons.

“I think I’ve already made cutbacks as far as I can. I don’t drive a car. I don’t smoke. I don’t buy magazines,” said Sarah Spoor, mother of two sons with rare medical conditions. “I should be having the heating on because we’re home, but I’ve barely had the heating on over the whole winter because I was too scared of what the bills might be. ”

When her eldest son was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes at the age of three, Sarah’s life as an unpaid carer began. In 2012, the aggravation of her sons’ condition required Sarah to spend more time caring for them.

“[They] need 24-hour care. They lose cognition multiple times a day and become unwell very quickly,” said Sarah. “I’m working 160 hours a week because they need someone there all the time.”

Since the pandemic began, due to an overwhelmed medical system and a shortage of professional carers, more and more people became full-time unpaid carers. According to Cardiff and Vale University Health Board, the number of people needing care at home has increased by 30% after the Covid outbreak.

Jake Smith, who is the Policy Officer of Carers Wales, said that a large number of care services were closed during the pandemic.

“Many of services that carers used to rely on before the pandemic, like days centres or Respite opportunities, have been withdrawn so carers are having to care for longer … It’s harder for unpaid carers to work alongside their caring.”

While most people’s lives seem to have restarted, the impact of the Covid on unpaid carers continues.

“Because of the pandemic we’ve been home since February 2020, we’re not going out because for us the risk of Covid is too high,” said Sarah. “Our life has become very small, I think you’ll find that lots of carers are still at home.”

Unable to leave home means no income from work, higher electricity bills, and mental pressure due to lack of social contact and connection with friends. The UK’s cost of living crisis is acting as an accelerator, driving everything towards a worse situation.

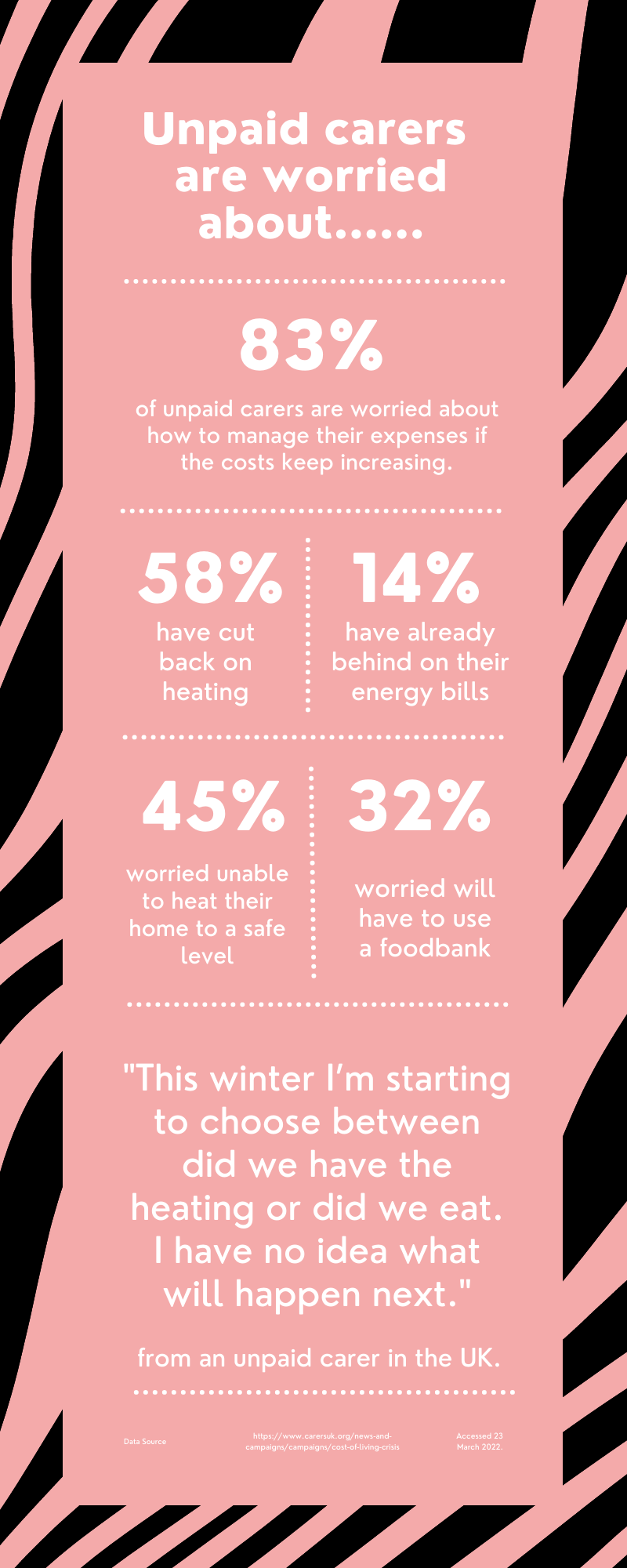

“Everything is going on. This winter I’m starting to choose between did we have the heating or did we eat. I have no idea what will happen next,” said Sarah.

“Because my children have special diets … so we’re not buying from the cheapest shops. Every week I’m spending about 130 pounds and that used to be about 90. I buy lots of cans of beans and chickpeas, I suppose I could start buying the actual bean and soaking and that would save money.”

According to a report published last December by Carers Wales, unpaid carers have to pay on average 1300 pounds one year out of their own pockets to provide care.

Jake said: “For many health conditions, it’s important to have good heating in the house to keep people warm at all times, which means that many unpaid carers can face additional heating costs.”

Mike O’Brien, an unpaid carer in Wales, is working with the We Care Campaign on collecting data of unpaid carers’ weekly breakdowns to prepare for running a digital campaign around the cost of living. He said: “Inflation is pretty shocking.”

However, the Carers’ Allowance, on which many unpaid carers rely, is increasing at a much slower rate than inflation and is not sufficient to allow them to meet the electricity bill for the fridge that holds insulin, the energy bill to keep the house warm or the cost of purchasing the equipment needed by the person being cared for.

“The rates of unpaid Carers’ Allowance is far too low, it’s less than 70 pounds a week. At the moment, the allowance is only due to being increased by 3.1% this April, but as we know the rates of inflation are expected to reach over 7%, significantly higher than that,” said Jake.

Only carers who spend more than 35 hours a week caring are eligible for Carers’ Allowance. Yesterday, the Welsh Government announced a 500 pounds recognition for carers, but only those eligible for the carer’s allowance will receive it – about 57,000 people, the number only accounts for about 1/7 Welsh unpaid carers.

“For example, Carers’ Allowance isn’t open to anyone who receives a pension. So the 500 pounds payment, although it is welcome and it will benefit many unpaid carers … Many unpaid carers will miss out on the payment,” said Jake.

In addition to Carers’ Allowance, Sarah’s sons receive the highest level of Personal Independence Payment. However, in order to meet living costs, Sarah still needs to apply for other discounts, and the process of finding information on these benefits was not smooth.

“I’m perhaps more able than some people to find out what benefits I can apply for, but even I didn’t know about the warm winter homes discount until last year. I’ve just applied for a discount on the water … nobody told me that was possible,” said Sarah.

Carers Wales is calling on the UK Government to relax eligibility for Carers’ Allowance and for the Welsh Government to restore and reopen care services in Wales so that unpaid carers can get help from the community. However, lots of unpaid carers have no faith that the status is going to be better.

Jake said: “Unfortunately, the majority of unpaid carers predict the situation will get even worse. [Our] research found that the majority of unpaid carers felt that the local services for them would be reduced even more in 2022.”

“When you consider that two years on from the pandemic, we’re still seeing significant disruption to carers services, and we’re still seeing carers having to provide more care with less support, it’s easy to understand why many unpaid carers feel quite cynical and fearful about the future. Because they haven’t really seen anything improve in the last two years. And if anything, it’s gotten worse for them.”