Cardiff researchers have stumbled upon a way to produce crucial acid in a sustainable way. How will this impact the fight against climate change?

Imagine a world where the chemicals in your clothes, cleaning products, and food preservatives are no longer derived from fossil fuels but from sustainable sources instead. That world might be closer than you think, thanks to a chance discovery by researchers in Cardiff and Beijing.

While experimenting with a new compound to produce hydrogen without generating harmful CO2 emissions, scientists from Cardiff University and Peking University, China, stumbled upon something unexpected: a method to produce millions of tons of a crucial acid compound in a way that could revolutionize the chemical industry, which is responsible for 6% of global CO2 emissions.

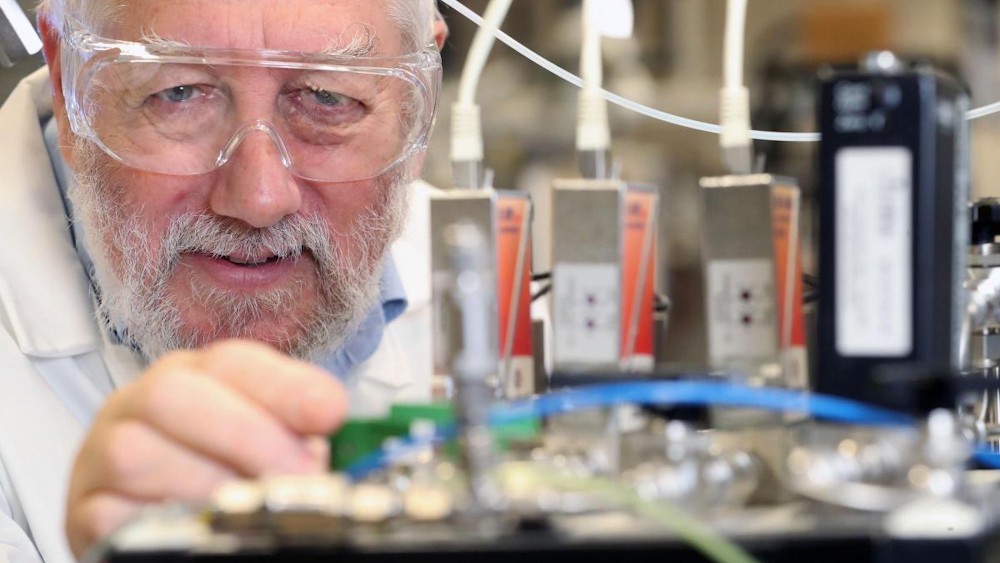

The joint research was led by Regius Professor of Chemistry Graham Hutchings from Cardiff University and Professor Ding Ma from Peking University in Beijing, China.

“Every year, 12 million tons of acetic acid are produced globally using fossil carbon sources,” said Hutchings. “If this process becomes fully functional, it could help reduce the chemical industry’s reliance on fossil fuels and support the goal of net-zero carbon production.”

The discovery was made while researchers were testing a new catalyst – a chemical compound that speeds up a reaction, to produce hydrogen without generating CO2, a major contributor to climate change.

According to Professor Hutchings, the original goal was to produce hydrogen without CO2 emissions. However, the process unexpectedly produced acetic acid, the same type of organic acid found in vinegar, broadening the focus toward creating this valuable chemical in a sustainable way.

Hutchings highlighted the broader impact of this discovery on the chemical industry. “The industry cannot be completely decarbonized since over 100,000 daily-use chemicals contain carbon,” said Hutchings. “But we can reduce our dependence on fossil-based sources like natural gas, oil, and coal.”

He further explained that CO2 acts as a building block for many chemicals. Hydrogen is needed to produce CO2 based chemicals, but current hydrogen production methods rely on fossil fuels, contributing to emissions.

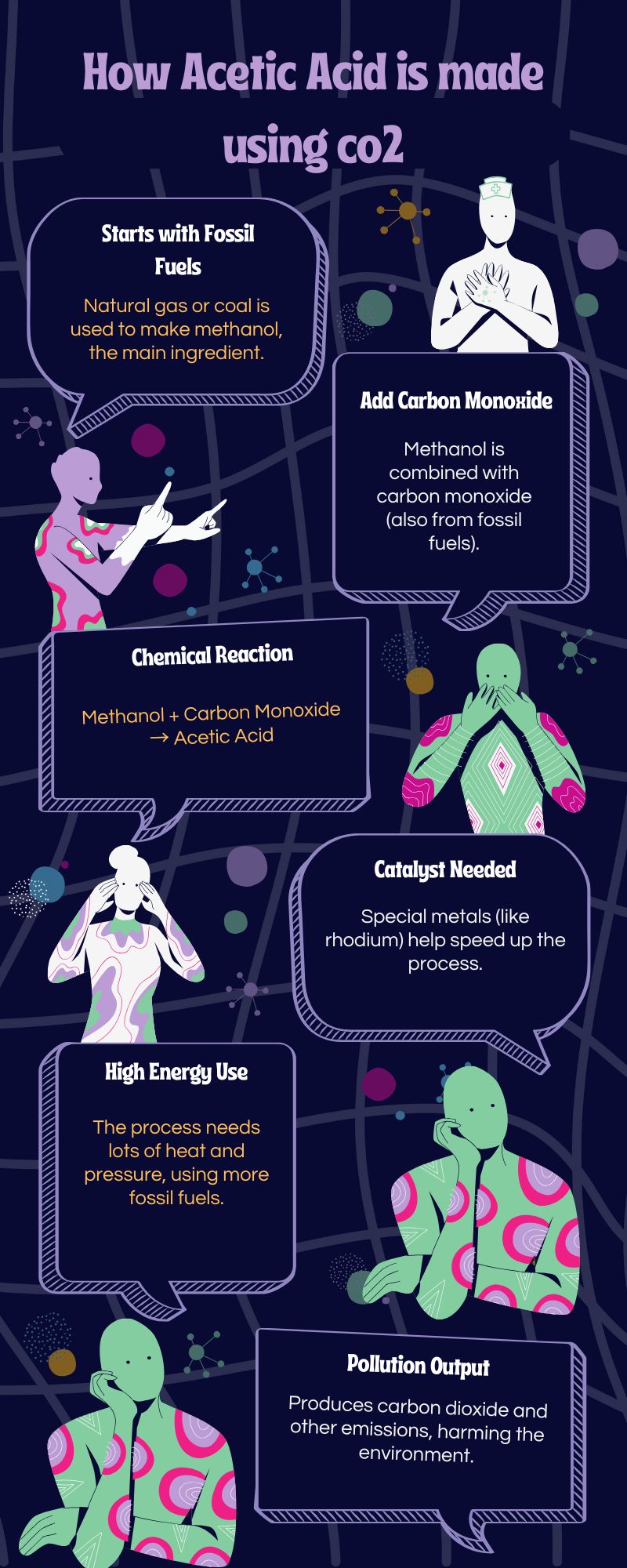

Traditionally, hydrogen is produced using methane through a process called steam reforming, which releases carbon monoxide (CO) and CO2 as by-products. The researchers replaced methane with ethanol sourced from biowaste, such as sugar crops. While this method produced hydrogen, it also generated CO2.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), approximately 96% of global hydrogen production relies on fossil fuels, emitting 9-12 tons of CO2 per ton of hydrogen.

“To eliminate CO2 production, we created a new catalyst,” said Hutchings. “It combines platinum and iridium nanoparticles supported on molybdenum carbide.”

Over a decade of research with metal-carbide catalysts for hydrogen production led to an unexpected outcome. “The reaction not only stopped CO2 production but also created acetic acid as a by-product,” said Hutchings.

However, the researchers noted that the new process faces challenges. “We need hundreds of millions of tons of hydrogen to meet global demand, but this method currently produces only a few million tons,” said Hutchings. “Our immediate focus is on producing acetic acid, which could replace the current methane-based process.”

Acetic acid is a high-value organic compound widely used in the chemical industry.

The research paper, entitled “Thermal catalytic reforming for hydrogen production with zero CO2 emission,” was published in the journal Science.

Hutchings acknowledged that implementing this discovery at industrial scale will take time.

His experience with a similar discovery involving PVC production provides useful insight. Earlier mercury was widely used as a catalyst to produce vinyl chloride, the building block of PVC, a compound whose usage ranges from pipes to clothes. Although Mercury is a toxic substance and is linked to birth defects and diseases like the Minamata disease, it’s importance for the PVC production ensured its continued usage. Things changed when Hutching’s research led to the development and usage of gold catalyst instead of mercury, leading to major industry reforms, but the change took years.

“I made the discovery in the 1980s, but it wasn’t fully commercialized until 2015,” said Hutchings. “It took decades for the industry to adopt the change.”

China, which once used 60% of global mercury production for PVC manufacturing, adopted Hutchings’ process, along with signing the Minamata Convention in 2013, which was ratified in 2016 and became international law in 2017. The treaty aims to protect human health and the environment from mercury exposure.

Hutchings chaired a policy briefing for the Royal Society last year on ‘Defossilising the Chemical Industry.’ He believes that this new discovery could play a key role in reducing the industry’s dependence on fossil fuels.

However, with this new breakthrough, Hutchings is prepared for a similarly lengthy process before any change happens. “By publishing our findings, we hope to encourage the industry to collaborate with us,” he said. “As scientists, our role is to make discoveries and show new paths forward. It’s up to the industry to adopt and commercialize these ideas.”