As the broken food system is discussed nationally, what progress has Wales already made tackling the issue of food waste?

Communities in the south of Wales are doing great work in tackling the scandal of food waste, which, in the UK alone, 2 million tonnes of produce is thrown away each year.

Yesterday, the National Food Waste Conference convened in London to discuss the scenario, responsible for 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions and occurring simultaneously alongside epidemics of obesity and undernutrition.

The issue was highlighted last year as Environment Secretary Michael Gove allocated an extra £15 million to combat the problem, however recent data from the government website StatsWales reveals the progress Wales has made on food waste dating back to 2012.

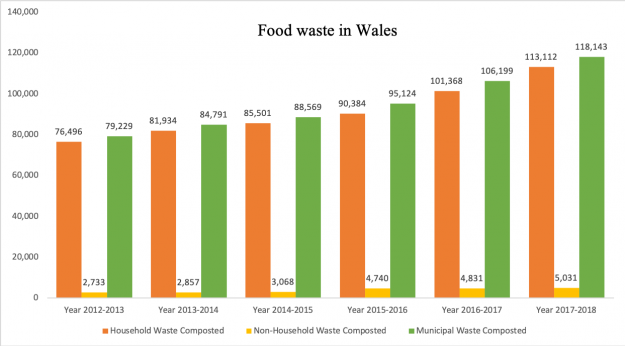

In the period from 2012-2018 InterCardiff analysis shows a 54% increase in the food waste reused, recycled or composted across Wales, from 79,229 tonnes to 118,143 tonnes.

The kerbside food waste caddies, introduced first in Cardiff in 2010, which now ensure that 99% of households across the country are covered by separate local authority food waste collections, are likely to have been a significant contributing factor in aiding the garbage mess.

Such progress comes in the context of how this month Wales has been named as the third best recycler in the world, with rates only bettered by Singapore and Germany.

Although already a signatory to the voluntary Courtauld 2025 agreement to make the food and drink system more sustainable, Cabinet Secretary Lesley Griffiths has also pledged to halve Welsh food waste by 2025.

“If just half of all the food and dry recyclables found in Wales’ bins were recycled, Wales would reach its 2025 recycling target of 70% nine years early,” Ms Griffiths said.

However, dealing with food already in the bin is not the only progress being made in Wales, as third sector organisations are now well established at working to reduce food waste while also providing a valuable service to vulnerable and disadvantaged people.

“Food is great in bringing people together, and it also helps them save money they can then reinvest on what else they really need,” said Sarah Germaine, Project Manager at Fare Share Cymru.

Massive thank you to our volunteers who put in more than 894 volunteer hours in February to help redistribute food to our partner charities! pic.twitter.com/otvERoNOWG

— FareShare Cymru (@FareShareCymru) March 7, 2019

The independent charity, set up in 2010, is responsible for saving 50 tonnes of food waste per month in South Wales alone, and providing it to organisations such as homeless hostels, refugee centers, and women’s refuge institutions.

Sarah explains, “What averages out to 1.2 million meals a year comes from a whole host of contributors throughout the chain, from farmers fields and wholesalers, to the distribution centres of supermarkets.”

“It’s surplus food, it can be overproduced or over ordered, sometimes even damaged food. Or for example, recently with the weather changes, food is already in the food production process, so when something changes there is going to be a surplus.”

What Fare Share does not do, however, is receive waste food directly from supermarkets. The grey area created by the Food Standards Agency’s sell by, best before, and use by dates does give a chance to use food fit for eating, even after the supermarkets can no longer sell it. However, for initiatives looking to utilise this window of opportunity, more regulation works against them.

Charges brought against The Real Junk Food Project (TRJFP), in 2017 highlighted the issue. The charity, started in Leeds by chef Adam Smith, aims to combat the food waste problem by collecting all the produce that would be thrown away and prepare it for public consumption.

The project has done remarkably well, with warehouses dubbed ‘share houses’ in Sheffield, Birmingham and Leeds, and 127 affiliated cafes, receiving food from supermarkets, food banks, farms and wholesalers.

Nevertheless, Smith faced prosecution as West Yorkshire Trading Standards Services (WYTSS) found 444 items past their use by date in the Leeds share house, and the charity was charged with “making food unfit for human consumption available to the public.” Smith said they had been doing so “without complaint” since opening.

Such bureaucratic rigidity can impede initiatives aiming to help the issue, and locally, The Embassy Café in Cathays, which had associated with TRJFP from 2016 to 2018, ceased its connection last year.

Innovative apps are one way to get around the problem. Last year Fare Share launched Fare Share Go, to connect individuals, charities and community groups with supporting supermarkets including Tesco, Asda and Waitrose. Though to prevent recrimination, the website states clearly, “the food available to you is good quality food that can no longer be sold.”

Another service is Too Good to Go, which connects food retailers such as restaurants, cafes, and hotels to discount hunting customers with food near the end of the period it can be sold. This has proven to be popular in Cardiff as companies such as YO! Sushi, Pettigrew Tea Rooms, and Deli Fuego taking the opportunity to sell on what they can before it has to go in the bin.

.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }

When it comes to whether UK supermarkets are doing enough to tackle the food waste problem, Sarah says, “they are doing a lot more than a few years ago. It is a tricky thing for the supermarkets because wasting food does cost them money.

“Food is a hard thing to get right, there is always more to be done looking at systems, and we could always use more food.”