Psychology professor debunks the main misconceptions behind infamous disorder.

ADHD. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

It’s a condition which has made headlines for decades, raising questions about parenting, classroom management, over-diagnosis, and the medicating of children.

Dr Kate Langley, researcher and senior lecturer at Cardiff University’s school of developmental & health psychology, feels that the public’s perception of ADHD is deeply divorced from its scientific reality. “ADHD is extraordinarily misunderstood,” says Langley. “I think it’s one of our jobs as researchers to try and help reduce the stigma that’s attached to it. ADHD gets a really bad rep. And it shouldn’t do.”

Dr Langley is part of a global team studying the disorder. They’re researching its causes, both genetic and environmental; its overlap with other mental health problems; its long-term effects past childhood; and ultimately, ways to help ADHD patients and their families.

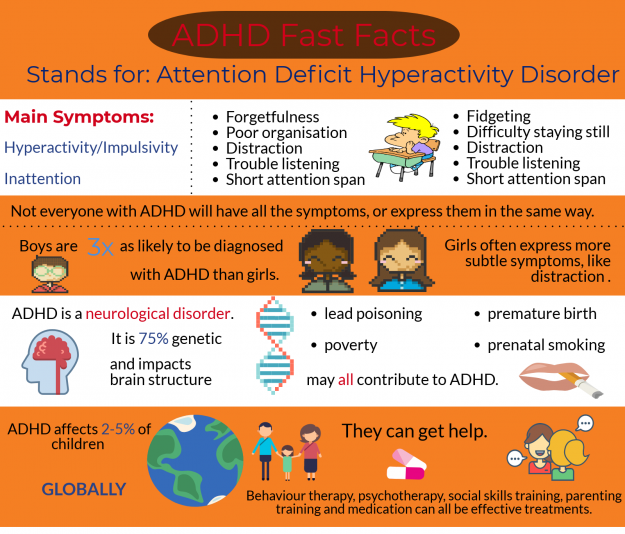

So what is ADHD? “ADHD is made up of three main difficulties. Problems with inattention, problems with hyperactivity, and problems with impulsivity,” explains Langley. “And those problems have to be present across a range of different situations.

“The important thing, which sets it apart from the fact that we can all find it difficult to concentrate sometimes, is these difficulties actually have implications and consequences for the individuals and the families themselves.”

Those consequences can take a wide variety of forms, negatively impacting schoolwork, friendships and family life.

The presentation of symptoms themselves are also extremely variable. Langley says, “You can have some people who have more inattention problems, but not so much hyperactivity and impulsivity, and vice versa.

“We also see that these things change over time as well. As people grow older, often what happens is that inattention keeps being a problem, and sometimes hyperactivity decreases, and so on.”

While the core symptoms are the same, ADHD is not a monolithic condition. That shouldn’t be so surprising. As Dr Langley says, “We are all quite complex people, aren’t we?”

The cause of ADHD isn’t bad parenting, and it’s not too much sugar. Overwhelmingly, it’s your genes.

“About 75% of the causes of ADHD across all individuals is due to genetic factors,” says Dr Langley.

.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }

Her team has collected data from 250 000 patients with ADHD, and they’ve currently identified 12 genes which affects a person’s risk of developing the condition.

“It’s not just 12. We know that’s not going to be the case. For example, in schizophrenia there’s evidence of there being hundreds of genes,” says Langley. “What we think is we’ve captured maybe up to 20% of those variants that might be relevant overall. So we know that there’s a lot more that we need to look for.”

She’s quick to point out that remaining 25% still leaves a lot of room for environmental influence. “We know that it’s not nature vs nurture. We’ve sort of moved on from the idea that it has to be one or the other. It’s silly to think it can only be one or the other.”

Determining the difference is tricky. “It’s very difficult to pick everything apart.

“There’s a lot of evidence that having these difficulties is associated with doing less well economically,” says Dr Langley. The less financially secure a family is, the fewer resources and support systems they have to draw upon.

Furthermore, having ADHD puts people at greater risk of other mental health conditions, including depression, antisocial behaviours and conduct disorders. Understanding the interactions between these conditions, and how they impact one another, is an area which particularly fascinates Dr Langley.

Part of the difficulty is that one or more of a child’s parents often have ADHD themselves. “They’ve got both a genetic influence, and also they provide the environment for their children.” Twin and adoption studies therefore play a vital role in teasing these factors out.

“One of the most interesting findings that we have,” Langley says, leaning forward in her chair, eyes glittering, “is that we’ve found that in a family where a child has ADHD, if you have a father with ADHD, then actually, the mother and child seem to have a better relationship than when the father doesn’t have ADHD.

“We think that might be because the mother has a relationship with the father, and sort of gets him. Understands the way in which he works, and the things he does. And therefore, that gives them a better insight into their child.”

Do we see the reverse?

“No, unfortunately, we don’t.” Langley laughs. “It’s interesting in itself.”

Dr Langley didn’t originally set out to study ADHD. “I suppose I’ve always had an interest in developmental psychology, and the development of children, and how it relates to when things go wrong.” She grins ruefully. “But the true answer is that I left university, and I needed a job. And there was a job!”

She’s inspired by her “stellar” team at Cardiff University, with the innovation they bring to the table. Ultimately, though, she keeps coming back to the research participants themselves.

“The families give you such a great insight,” says Dr Langley, who’s personally involved in reaching out to them. “It’s one of the most important jobs, of course. But it’s also one of the ones that really helps you identify why you’re actually doing this job. You could take a very dispassionate view, and just pick two different things and study them, and be a sort of analyst instead of a researcher… But actually going out and meeting families—going out and finding out what it actually means to have ADHD, or have a child who has ADHD, is a really, really important part of what we do.”

That’s why she so detests the misconception that poor parenting causes ADHD. The children are not just being ‘naughty’, and they cannot just start acting differently. “Having a child with ADHD is much more difficult to deal with, to parent.”

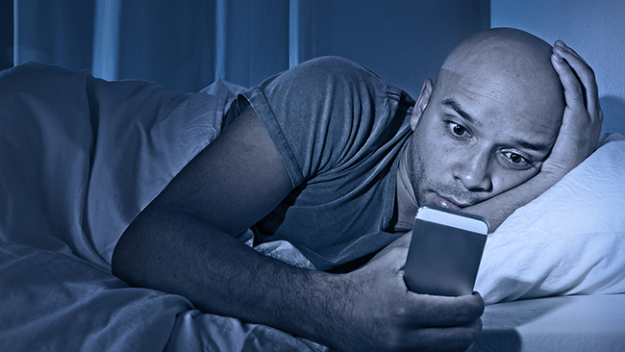

It’s the families that help give future directions for research. It was parents that suggested the connection between ADHD and sleep disorders, and investigating what happens to patients once they grow up.

“There’s a growing recognition that ADHD doesn’t just stop in the classroom,” Dr. Langley says. They’re reaching out to past participants to continue contributing—a difficult task when children begin moving away and spreading out, but hopefully the rewards will be worth the effort.

Now that they’ve identified 12 gene variants that cause ADHD, “the next bit is to work out what they do and how these genes are relevant.”

Would understanding how these genes work provide earlier diagnosis and genetic screening?

“It’s such a long, long way off that it’s almost not worth talking about it,” Dr Langley says, shaking her head. “But it is always an eventual aim.”

Short term, this research will understand exactly how these genes affect brain chemistry. If those chemicals can be targeted, then new medications can be developed.

In the meantime, it’s simply important to provide people individuals with the support they need. It’s also important for people to understand the nuance behind ADHD.

“None of us live in nice little silos. None of us are in sort of nice little boxes according to what kind of diagnosis we’ve got.”