Witchcraft has experienced a modern resurgence, with the last census in 2011 revealing that at least 83 people in the UK identify as a witch.

The workings of the witch are seemingly shrouded in mystery. The witch throughout history has been misunderstood, at best, and persecuted at worst.

However, modern science and witchcraft are not mutually exclusive. Here, we meet a scientist fascinated with the link between the two, who explains how science can provide backing to the magic.

The pendulum demonstrates the ‘ideomotor effect’, wherein the hand subconsciously moves where the user is expecting movement. This has been used to explain Ouija boards.

In her talk on science and witchcraft as part of the Cardiff Science Festival, Dr Styles explained that witchcraft has experienced a “surge in popularity” over recent years. “It enables us to reconnect with nature in the modern world,” she added.

Science, she says, can sometimes justify the unexplained. The spells a witch casts are likely to work because the witch believes in them. “If you know what you want and are focusing on that goal, scientific studies prove that you are more likely to achieve it.”

Dr Styles describes the use of a ‘charm bag’, which contains specific herbs picked for an effect and a statement of what the witch desires.

The charm bag, for example, may help a witch make amends with a friend because their belief that the charm will work enables them to approach a conversation differently.

“Your body language may lower the cortisol in their blood, making them more relaxed and less likely to respond negatively,” Dr Styles explains.

Historically, witches faced persecution, though this was not as widespread in Wales as it was in England during its height in the 17th century. Five witches were executed in Wales, out of a total of 100,000 across Europe.

Traditionally thought of as local healers, many of witchcraft’s traditional uses of plants have since been backed by scientific evidence. Their ingredients form the basis of numerous modern medicines.

The lavender and chamomile in Dr Styles’ charm bag have been proven effective at reducing stress due to the chemical compound apigenin, which works in a similar way to some anti-anxiety drugs.

Similar, historic examples of medicinal plant usage can be found in The Apothecary’s Hall, an Edwardian-style pharmacy within the National Botanic Garden of Wales

It also has ties to Cardiff: the exhibition at the Hall was originally set up by Professor Terry Turner of Cardiff University, a researcher and lecturer in plant medicine (phytopharmacy).

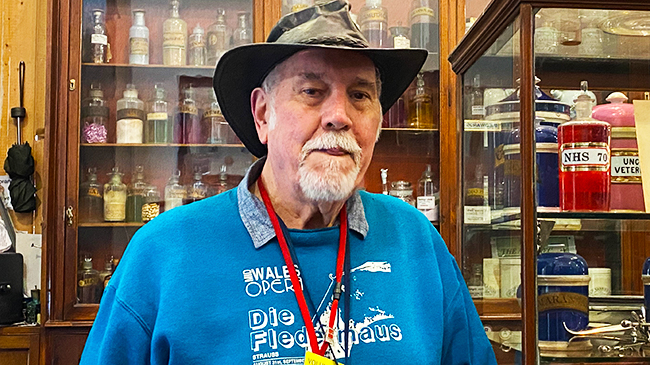

For Garden volunteer Bob Edwards, the Apothecary’s Hall is a source of great interest.

Many medicinal plants, he explains, have a basis in witchcraft. Witches would get a ‘feel’ for the uses of a plant, something Bob says may be attributed to absorption through the skin or familiarity in smell.

Even the use of flying broomsticks – a common witch stereotype – can be attributed to plant use.

Henbane, which Bob says was traditionally “beloved by witches”, is a psychoactive wild plant common in some areas of the UK.

It can produce feelings of euphoria and sensations of flying and would be applied where the skin was thinnest, such as intimate areas and sinuses.

A polished broom handle would sometimes be used for its application, hence the folkloric image of witches flying on broomsticks. The image of the witch atop a broomstick still pervades today.

Hyoscine, an active ingredient of henbane, can slow down signals between the balance organs in the ear and brain receptors. It has applications in modern medicine: it is used in travel sickness tablets as well as to treat symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome.

However, traditional uses do not always yield answers for contemporary medicine.

Mandrake plants are steeped in folklore. When pulled from the ground, they sound as though they’re screaming. On some nights, the plants are said to be guarded by demons.

In reality, says Bob, the plant has a long, twisted root and will often produce squeaking noises when pulled up from the soil. This isn’t unique to the mandrake and can be observed in other root vegetables.

The demonic guards seen around the mandrake plants can be explained by the fact that North African glow worms seek protection within its leaves. The ‘demons’ themselves are actually being ‘guarded’ by the plant.

The mandrake is used in folk medicine as a sedative and painkiller. Traditionally, it was used in combination with henbane and other substances such as opium in a ‘soporific sponge’ to anaesthetise patients.

Despite these uses, it remains unapproved for use in conventional medicine due to the danger posed by the poisonous, hallucinogenic alkaloids present within the plant. Whilst one patient can fall into a deep sleep with a dose of mandrake, another might never wake up.

The cry of the mandrake is fatal to anyone who hears it.

Hermione Granger, of JK Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.

Beyond plants, the mystic of divinatory tarot readings is an allure for many to the occult.

Occult and esoteric subjects are “favourite” subjects of Swansea-based Kathryn Davis. She believes that, in addition to their prophetic uses, tarot cards can be a method of self-reflection and learning.

With tarot readings, we can “find greater reward and understanding of ourselves and the balance of life”, she says.

This meditative practice is similar to that of ‘mindfulness’, a tool advocated for mental illnesses such as depression. The patient is encouraged to be ‘mindful’ or aware of their thoughts, feelings and environment.

The beneficial effects of this are noted by Dr Styles. “Tarot readings can give an insight into your mental state, such as your ideas and perceptions.”

From plants to divinatory cards, practices in witchcraft have enduring applications in modern medicine. Science and magic intermingle more than you’d first expect.

For more information on the Apothecary’s Hall and the use of plants in medicine, please visit the official blog.