The history of South Wales is intertwined with ghost stories. As the long, cold nights draw in, we speak to experts in the supernatural about the origins of Glamorgan’s spookiest stories …

KARL-JAMES Langford never intended to write about ghosts.

As an archaeologist, author, part-time actor and candidate for Welsh nationalist party Gwlad in this year’s Senedd elections, he had little interest in ghost walks beyond using them as a tool to teach people about Welsh history.

“We were supposed to just do the history stuff, and then in the dark we’d do the ghost stories,” he said. “But everything started to intermingle.”

Now, Karl is the founder of Ghost Experience Cymru, a company that organises ghost walks across Cardiff and Glamorgan, and he has just published Ghosts of Glamorgan part 2, his second book on the subject.

He is now a firm believer both in the power of ghost stories to peel back the layers of history and in the ghosts themselves.

Karl has suggested we meet on Penrhys Hill, a picturesque viewpoint overlooking Rhondda Cynon Taf. We’re standing by the imposing statue of the Virgin Mary that dominates the hillside – a replica, carved in the 1950s based on medieval Welsh descriptions of the original.

“To read a landscape you need storytelling,” Karl tells me.

He gestures to a crumbling wall half-buried in the hillside, all that remains of the medieval monastery that once stood here.

“Landscape like this at the top of Penrhys Hill — it’s really calm today, but in the past there has been a lot of tumult.”

Landscape like this- it’s really calm today, but in the past there has been a lot of tumult

Karl-James Langford

Penrhys has a history that lends itself to ghost stories. The original statue of the Virgin Mary was a famous pilgrimage site in the medieval period, until it and the accompanying monastery were torn down in the 1530s on the orders of Thomas Cromwell.

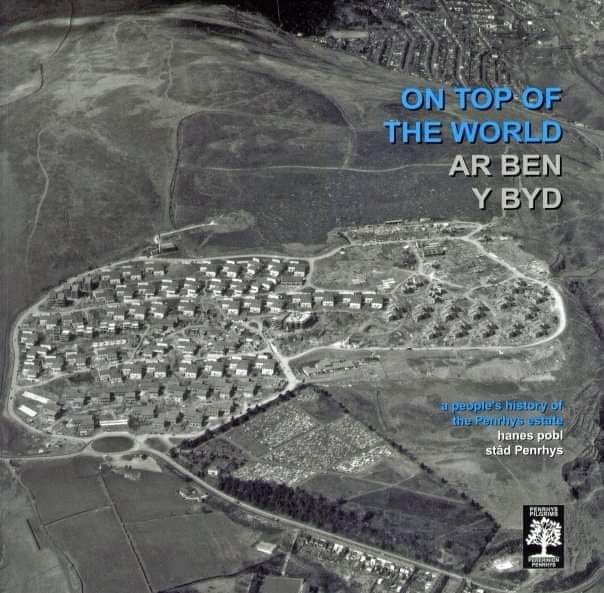

The modern era saw levels of poverty rise throughout the Rhondda. Formerly the site of a smallpox hospital, Penrhys was selected as the location for a brand-new estate in 1966. Nearly a thousand houses were built, of which only 300 remain.

Initially hailed as a triumph of modern planning, the Penrhys estate quickly ran into problems.

“They built it in precisely the wrong place,” said Karl. “There were no train stations, no supermarkets – it’s in the middle of nowhere.”

As demand for mining in the area dropped off, the unemployment and crime rates in Penrhys skyrocketed. By 1990, one resident estimated that 93% of the population was unemployed.

“Until the 1990s that estate was rife with allegations of poverty and crime,” said Karl.

“That’s when we started hearing one or two ghost stories.”

The stories that Karl uncovered are rooted in Penrhys’ complicated past. Dean Drakes, who grew up on the estate, describes it as dumping ground for “social rejects”.

“It was like a war ground once,” he said. “But even with all that it was still a surprisingly lovely place.”

In Karl’s book, Ghosts of Glamorgan part 2, he recalls hearing about “dark hooded figures” and ghostly monks who stalked the police stations on the estate.

Dean told Karl that the supernatural activity in the area got so bad that the site of the monastery had to be blessed by a priest, who walked up Heol Pendryus and back again, “saying prayers and using holy water”.

For Karl, stories like these are cultural memories that fill the gaps left by the physical remains of the past. He describes them as “echoes” that have been forgotten or ignored by academics.

“Archaeologists are usually boring people,” he tells me. “You could say: “‘Oh actually there’s a bit of a monastery wall over there’ – but you’ve got to give voices to those things.”

Karl is not alone in his interest in the ghosts of South Wales.

“Ghosts have become fashionable,” said Dr Juliette Wood, Cardiff University’s resident expert in Welsh folklore.

“There is hardly a heritage site in Western Europe that does not do a ghost tour, so all of a sudden these places are full of ghosts.”

Dr Wood has spent the last three decades collecting Welsh folklore, and knows better than anyone how closely intertwined ghost stories are with Welsh history.

She tells me that the third Marquess of Bute, the son of Cardiff’s modern founder, was an enthusiastic ghost hunter. Allegedly, the statue of his son Ninian in the city centre becomes a hotspot of supernatural activity around election times.

Ghosts are common in Welsh folklore, from the White Lady who haunts roads and bridges to the Toili, ghostly funeral marches that warn of impending doom (if you see the Toili, the story goes, then the person in the coffin is you).

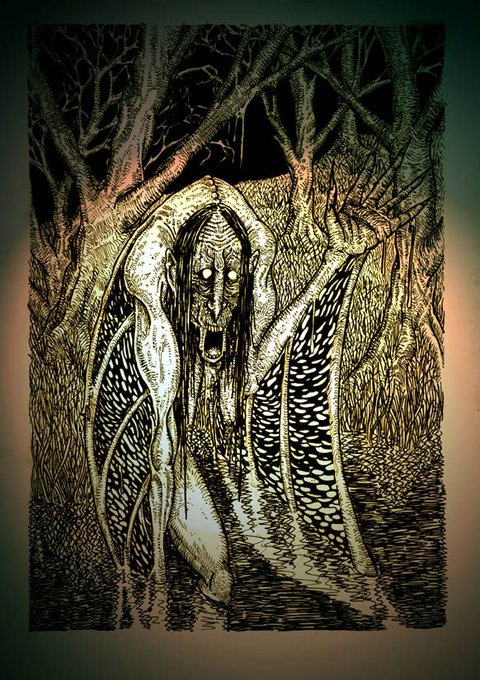

Another famous Welsh portent, the Gwrach y Rhibyn, makes multiple appearances in Karl’s book. This “hideous winged hag” appears, screaming and howling, outside its victims’ window to warn them of their death.

The Gwrach is a fixture of modern Welsh folklore, but Dr Wood explains that this was not always the case.

“Originally she was a kind of plague demon,” she said. “The story goes, if you meet her on the marshes outside Aberystwyth, you’ll develop a fever.”

The Gwrach, Dr Wood explains, was relocated to Cardiff by Marie Trevelyan, a 19th century folklorist who helped cement the popular perception of Welsh folklore.

“The Gwrch y Rhiwbyn has become this elaborate story about witches and goddesses,” said Dr Wood.

“When you get something like that, it roots itself in popular culture, and you get other people saying, ‘Oh yes, I saw the Gwrach’.’”

This complex interchange of stories is typical of Cardiff and Glamorgan, areas that have changed dramatically over the past few centuries.

“Cardiff was almost a fishing village before the Marquess of Bute arrived,” said Dr Wood. “The city was transformed by the coal industry in the 19th century. It’s not like other cities, where you trip over old buildings. Cardiff is an industrial city, so it has industrial stories.”

“All of these people that came here for the industry had to create new communities. And if you want new communities, you have to create new customs.”

So why does Glamorgan have so many ghost stories? Back on Penrhys hill, Karl pauses, before giving me the academic answer. As the county with the highest population in Wales, it makes sense that Glamorgan would provide the most sightings.

“But I also think Glamorgan has suffered the most,” he said. Some of this suffering, he says, goes all the way back to the conquest by the Normans and Owain Glyndwr’s rebellion. But many of the wounds are far more recent.

“Billions of pounds were made on the backs of these people mining,” said Karl, gesturing to the surrounding valley. “That money never came back here. The miners had to fund the construction of their own community homes, their own churches – even the construction of the statue here.”

“These are the people who really suffered. The Senghenydd disaster, over 400 people died; Aberfan, over 120 people died. All this suffering, and it’s almost ignored.”

“I don’t think it’s because there are more ghosts, but instead more reasons to have ghost stories”

Dr Juliette Wood

Dr Wood admits that she has come across ghost stories that have sprung from these modern tragedies, including stories associated with the Senghenydd disaster.

It’s to be expected, she says, from events that leave such a devastating imprint, and forms part of a wider tradition of using these stories as a way of remembering and recovering from catastrophic loss.

“Often, at a funeral, someone will say, ‘I heard the Toili a week before so-and-so passed away’,” she said. “In a sense, they are saying that although we’ve lost someone in a community, the community is still there. I think it is a way of healing.

“You get a lot of stuff in this area, because a lot of stuff has happened – I don’t think it’s necessarily because there are more ghosts, but instead more reasons to have ghost stories.”

- Ghost Experience Cymru run ghost walks throughout the year. Ghosts of Glamorgan part 2, by Karl-James Langford is available to purchase here.