A look at the past, present and future of the Glamorganshire Canal

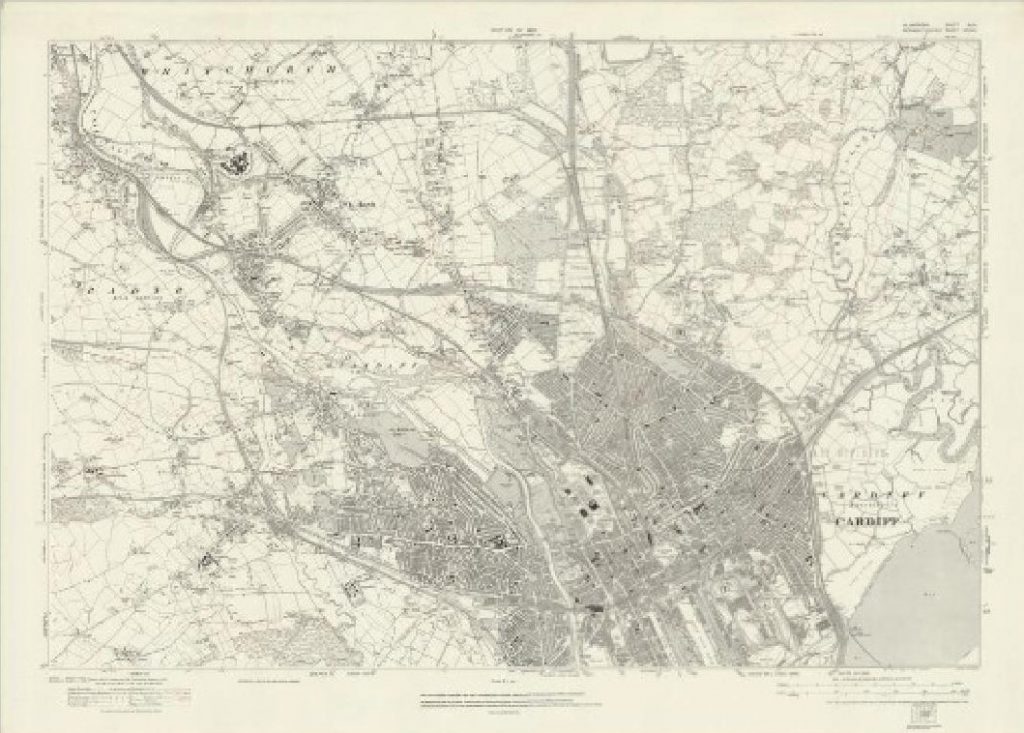

IT may be mostly buried beneath concrete now, but in the 18th and 19th centuries the Glamorganshire Canal was essential in bringing economic development to South Wales.

It is hard to imagine what Cardiff was like then — a small town of just 20,000 people when today it has a population of 360,000. To fully understand how this transformation came about, we have to go back to the start of Welsh transport – the Glamorganshire canal.

In the 18th century transport meant horses and carts on uneven, muddy roads. The Glamorganshire canal was built between Merthyr Tydfil and Cardiff as a more effective mode of transporting people and goods.

The Glamorganshire canal was for a time, the most financially successful waterway in Britain. It rose by over 500ft across 25 ½ miles by use of 51 locks; these locks allowed water to be fed into different sections of the canal to raise the barges in height as the water level rose.

With a quick transport link, towns like Merthyr Tydfil were able to transport iron, limestone, and coal that were found in the Heads of the Valleys of South Wales, on an industrial scale.

The canal’s sea basin was then linked to Cardiff’s port to create a national transport network, which would later become global. The canal brought economic and industrial growth on its watery journey through the Welsh countryside.

Callum Couper, 62 from Penarth, is a former port manager who worked at South Wales and other UK ports. He has been fascinated by the canal throughout his working life.

The Glamorganshire canal was a vital transport link allowing the iron works of South Wales to supply a rapidly growing demand at home and internationally. It was the cutting-edge infrastructure of its day as smart as any transport system that exists in our modern age.”

Callum Couper

“The Glamorganshire canal was a vital transport link allowing the iron works of South Wales to supply a rapidly growing demand at home and internationally. It was the cutting-edge infrastructure of its day as smart as any transport system that exists in our modern age,” he said.

If you want to follow its historic route, just take a drive up the A470 between Cardiff and Merthyr Tydfil. Alternatively, use the road underpass that goes under Castle Street at Kingsway – you will be walking the same way that the bargemen went on their journey.

The canal in its prime

The canal was a lifeline in deprived rural areas of Wales in the 18th and 19th centuries, providing jobs for many.

The barge journey from Meyrthr to Cardiff took around 20 hours, with time added for the necessary overnight stops.

In 2001 and 2004 Ian Wright and Stephen Rowson wrote two history books about the canal. They interviewed William Gomer, a former bargeman.

“I’ve been up at 4am and gone to bed at midnight to try to get a living, and if you worked for the company on the Merthyr boats, then 16 hours was considered a working day. Only after that would you get your bonus,” he said.

Letters were the main mode of communication in the 18th and 19th centuries, so bargemen were revered as knowledgeable news carriers, picking up stories and passing them on during their travels.

Tracking the families who lived and worked on the water in those days is difficult. However, John Fletcher, a retired headteacher from Swansea, managed to do just that.

Through Ancestry.com he found over 40 members of the Fletcher clan descended from Daniel Philip Fletcher.

The first family reunion happened in Pontypridd in 2010, where ancestor Daniel lived with his nine children while working on the Glamorganshire canal in 1839. Some descendants came from as far as Canada and South Africa to meet their newly found relatives.

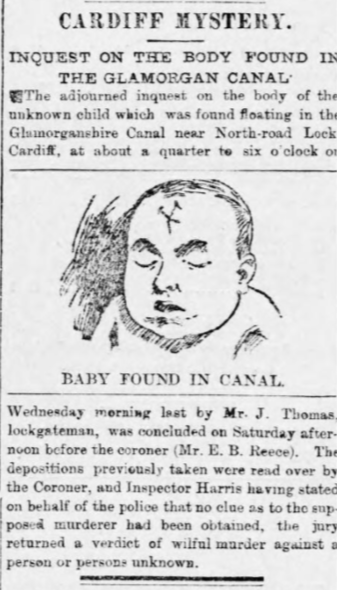

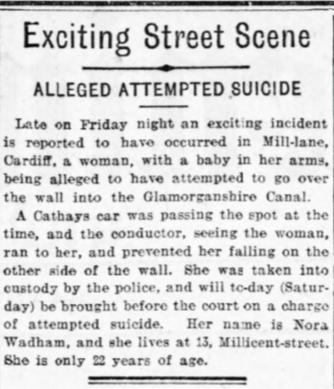

The darker side of the canal

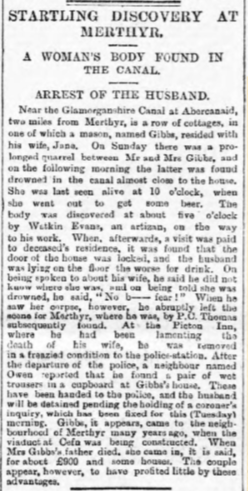

Historic newspaper clippings tell a much darker tale of the canal than the history books. Nicknamed “The Black Ribbon”, the canal was a watery death for many. It became a hotspot for infanticides, suicides, and murders.

The flow of boatmen on the canal also meant that certain services, such as beerhouses and brothels, were popular along the banks.

For example, the canal used to flow in front of the bar Peppermint, formerly known as the Terminus Hotel, on the corner of Mill Lane and St Mary Street. For twenty years between the 1850s and 1870s, the housing opposite the canal here was known as the red-light district of Cardiff.

The modern impact of the canal

The canal may not be visible to modern day city-goers, but its importance has filtered down through the generations.

I found an example of one on a frosty morning in Pontypridd between a Sainsbury’s and The Bunch of Grapes pub car park. Nestled below Ynysangharad Road was the last remaining double lock of the Glamorganshire canal, and the men who are renovating it.

Talking to Ron Keats, a member of the group, it was clear that the canal still has importance in the modern Pontypridd community as part of their heritage.

Brown Lenox & Co Ltd, a chain and anchor manufacturer, had destroyed parts of the lock, added pipework, and cemented the sides to retain water integrity while using the locks as water tanks.

In 2010, the group started work on the canal. They had to work by hand to restore the locks to their former glory as there was no access for machinery.

There was 5ft of silt in the bottom lock and 1.5ft in the top lock, which meant that work depended entirely on the weather; rain made conditions too dangerous, creating a drowning hazard.

Mr Keats said: “The motivation was to try and restore what was part of the industrial heritage of the area. It was seen as something that was a big part of Pontypridd development.

“It was all overgrown – it had been left to decay and nature had taken over in terms of roots displacing a lot of the stonework.”

The group meets twice a week and enjoy each other’s company, physical labour, and the reward of putting a piece of history back together.

Mr Keats said: “I retired, and I was looking for something to get involved with.

“This project was something that ticked several boxes, physical work, a weekly structure, the camaraderie. That was the motivation for me. I also got interested in the history of it all – it was really intriguing.”

To maintain authenticity, the group use original materials where they can. Having found some of the stones at the bottom of the lock, they fill the gaps with Blue Pennant and lime mortar – the same materials originally used.

“The bridges we had to build – we were lucky the footprint of the bridge was left in the mortar so we could get dimensions. Then, using historical images, we were able to reverse engineer how they looked.”

In the 1970s there was a local movement for the remains of the canal to be made into a nature reserve after a rare plant species of Arrowhead was discovered. The plans fell through when Sainsburys won the contract to build on the retail park next to it.

“Now all we see are ducks and rats,” said Mr Keats.

The Glamorganshire canal may be mostly buried beneath urban development, but its memory lives on in a few knowledgeable people who have been touched by its history.