SOME people do a lot.

There are people you encounter every now and again, who just do more than the rest of us.

They have the same number of hours in the day as everyone else and yet, somehow, they cram multiple lives into one lifetime.

Kath Fisher is one of those annoyingly productive people – over her career she has worked as an air traffic controller in the RAF, as a bodyguard for Maria Sharapova, as a police officer in Barry and she currently works in a helicopter for South Wales police.

Oh, and she volunteers for the Royal National Lifeboat Institution.

When we meet for a drink, I am tucked up nicely in a chair, surrounded by gentle, jazz music and the smell of roasting coffee.

Kath meanwhile has already been on a call-out that morning helping to rescue three drunk, Russian sailors who went on a big night in Barry and ended up adrift in a dinghy.

Kath’s dad served in the RAF and thought that she would be well suited to a life in the military from a young age – clearly, she was.

She got her pilot’s licence at 17 and was sponsored through university by the Royal Air Force.

In her second year at university Kath took a trip to America.

“A friend and I hired two four-seater Cessnas, put six of our mates in the back and flew up the east coast.

“It was pre-9/11, so we were able to do orbits around the Statue of Liberty and stuff like that.

“It was odd, I was only 20 so I wasn’t old enough to buy a beer, but I could land a plane at an airport.”

In 1999, after she had finished university, Kath completed her officer training and signed up as an air traffic controller.

“After my initial six-year period was up in the RAF, I began to think it was time to try something different.

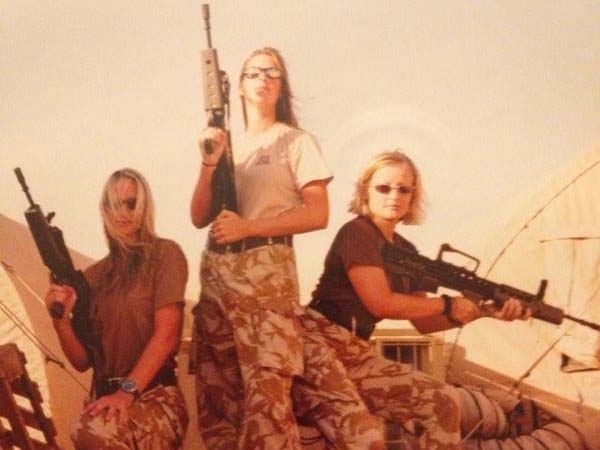

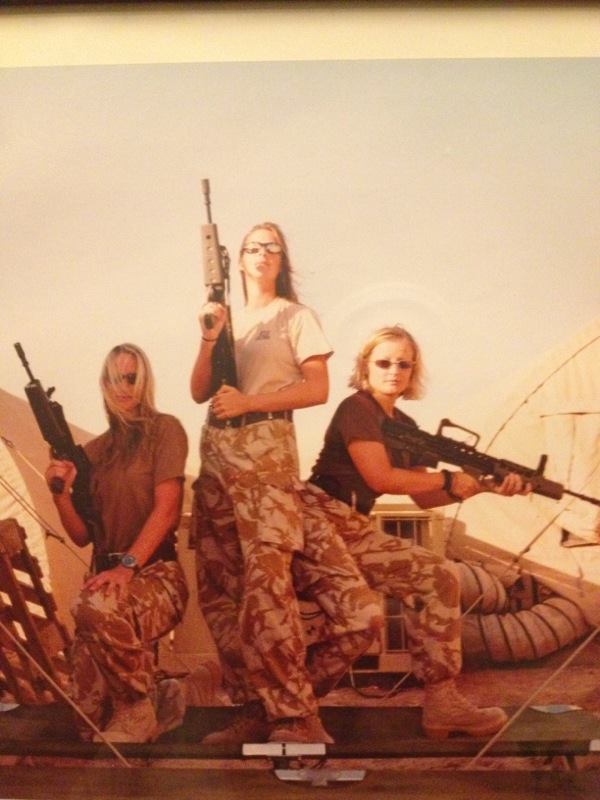

“I did a tour in Iraq in 2004 as an ATC and while I was there, I got chatting to the general’s bodyguard and began finding out what it was like to be a bodyguard.

“I found out you could do bodyguarding as a civilian and the military would pay for my re-training.”

Diving in at the deep end, for a change, Kath found herself protecting one of the biggest tennis stars in the world at the time: Maria Sharapova.

“I worked for her when she was at the height of her game when she was in the UK from 2007 to 2009.”

Although she never experienced any truly dangerous moments during the “bodyguard years” Kath said that she still doesn’t like to have her back to a room.

It’s true. Even now, tucked away in the safety of Penarth, Kath has her back to the wall as she sips her latte and talks quietly but assuredly.

“I like to see where everyone is, I want to know where all the exits are.

“Everything I have done in my life has forced me to always be thinking ahead, constantly thinking about what might go wrong and having back-ups.”

Perhaps, this is why there have been so many jobs, so many abrupt changes in direction – it must be hard to stay in one place if your mind is always darting ahead.

After a few years of looking after wealthy Saudi royals and their families in London, Kath moved back to Penarth.

She was looking for a normal job, one that allowed her to go home at the end of the day, something a little less stressful – so she became a police officer in Barry.

Looking up from my notes I can’t resist the urge to ask what was more dangerous – serving in Iraq, being a bodyguard or being a police officer?

“Barry without a doubt – and I got mortared in Basra,” Kath laughs.

Being a police officer was tough and Kath had to learn quickly.

“Before I joined up, I hadn’t spoken to any police officers or anything.

“I think I didn’t really know what the job entailed.”

In the UK, the armed forces are treated with reverence – the police on the other hand, are often targets of abuse – both from those they are trying to help and those they are trying to arrest.

“It was a shock to the system; you don’t really realise how some people have to live. I’ve had this nice life in the military and you just don’t realise what it’s like.”

Kath persevered for five years as a police officer, building relationships in the community and doing her job, but before she knew it, she was at it again – thinking ahead; tinkering with the future.

She was looking at surveillance jobs within the police, when a job as tactical flight officer on a police helicopter came up and she decided to go for it.

“It’s perfect, it suits me down to the ground, it’s everything I’ve learned.

“The way it works is we have one police officer in the front operating the camera and I’m in the back, I can see what the officer in the front is seeing but I also have all the mapping technology.

“I tell the pilot where to go while looking out the window and trying to co-ordinate where the officers on the ground are going.”

Police forces across Wales are struggling to deal with the growing mental health issues officers face as a result of the distressing work they do.

Kath says that the majority of their call-outs these days are to do with vulnerable missing people such as people with mental health problems, or dementia.

As social services face funding cuts, police are increasingly on the front line of mental health support.

We have finished our drinks and Kath is looking away, back to the wall.

“Do you remember, about a year ago there was an incident in Cardigan where a mum had got out of her car and left her child inside while she went into her house.”

When she came back outside the car was gone.

“When we got there in the helicopter our first thought, because it was all over social media, was that someone had nicked the car with the keys in and was driving around with the toddler in the back.”

As they flew around the town Kath noticed a white square in the river – the car had rolled down the hill it was parked on and gone into the water.

“I immediately got on the radio to the guys on the ground and made sure they could not be overheard by anyone involved.

“I told them I was pretty sure I had seen the car. They got one officer in the water but he couldn’t reach it.

“Then I just saw this figure launch, like Baywatch, into the water, swim to the car, smash the window and pull this little body out.

“The person who leapt in was a female PCSO. Male police officers hadn’t been able to get there and I don’t know if she was a mum, but she was like ‘I am getting into that car whatever happens’.”

Kath is still talking quietly but she has leaned forward in her chair, back no longer against the wall.

“They worked on her for about three hours but she had been underwater for about 90 minutes so they weren’t going to get her back.”

Living the lives Kath has, you can’t be ruled by emotion, you have to feel it but not be overwhelmed by completely overwhelming situations.

“As we were flying away, leaving it behind, I started crying and my colleague asked me if I was OK and I just said ‘no’.”

Sometimes, that’s too difficult.

Two years ago, Kath got involved with a charity that aims to help veterans from the armed forces and also members of the emergency services, who might be suffering with PTSD.

“Woody’s Lodge was set up in memory of Paul Woodland (a member of the Special Boat Service) who died in a training accident in Poole in 2012.”

“I’m a trustee on the board and basically it’s a charity that helps veterans, military primarily but all sorts – we help with anything, housing, finance or even just a cup of tea.

“There’s a lady there that helps people with form-filling. It’s only a little thing but when your head is not in the right place doing things like that can be very hard.”

I ask whether Kath wants to keep working at the National Police Air Service for the rest of her career. She says she could see herself doing that, but part of her wants to find something a little less intense in the future.

“I might join the RAF reserves and get into property …”

Some people do a lot – but Kath Fisher does it all.