People queue for hours to get halal meat, lentils, and gram flour from Butetown Food Pantry, where there’s a strict ‘no pork’ policy

WHERE do families who are looking for multicultural food turn as they struggle with food poverty in Cardiff?

It’s a question that the Butetown Food Pantry has answered by setting up a service providing BAME-friendly food.

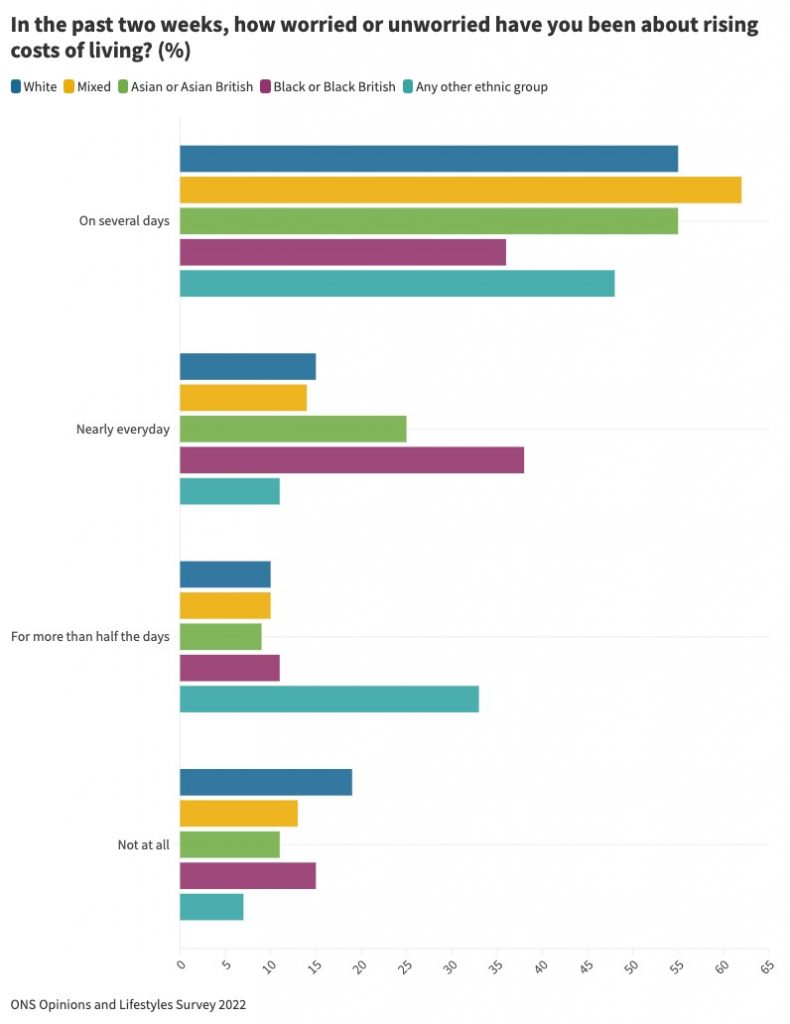

A recent ONS survey found that ethnic minorities were more concerned about the rising cost of living than white British people, who were the least worried. Asians, mixed race people and people from other ethnic groups worried less than black Brits, but more than white Brits.

And that’s why the pantry is offering customers, for just a few pounds, bags filled with food such as halal meat, lentils and spices.

It’s so popular that people start queuing hours before the doors open at Butetown Community Centre.

The food pantry believes it is the only one in Cardiff providing such a service.

“Food poverty projects are generally tailored to Caucasian palates, unsuitable for many of our immigrant customers from Somali and Yemeni backgrounds,” said Kervin Julien, a veteran food poverty activist.

The 61-year-old Londoner set up Butetown Food Pantry in January 2022.

Users pay £4 for a couple of carrier bags of food. They can also buy membership for a one-off £10 payment. This entitles members to food worth up to £20 for just £3.

The food pantry runs every Thursday from 12 noon to 3pm at the centre on Loudoun Square. But volunteers do not turn people away outside of these hours. Some customers are so desperate for food that they arrive at 9am.

The community centre’s reception is usually full of customers by 10am who wait patiently for their turn.

The pantry supplies halal meat and operates a strict no pork policy out of respect for Muslim customers.

Other items they offer include spices, fresh coriander, gram flour and lentils to cater to African and Asian customers.

Unlike food banks, the pantry is open to anyone. Customers are often Butetown residents, where Kervin has leafleted, but they also come from Canton, Splott and nearby Grangetown.

The registered charity has chosen not to be a part of any food bank scheme because of strict criteria.

“We don’t expect people to live in the area, fill in a long red form or provide benefits evidence because this excludes people that have no fixed address,” he said.

Kervin’s outreach journey

Kervin started feeding homeless people not in Cardiff but in Coventry in 2008, serving around 350 people a week. He would go out onto the street with his volunteers to give out toast.

“I’d buy 14 loaves of bread and lots of butter. After 18 months the Sainsbury’s cashier finally asked me why I was buying so many”

Kervin Julien, 61

“She introduced me to the manager who told me that I had served his nephew food. He wanted to collaborate with me straightaway.”

Because of this single Sainsbury’s interaction, Kervin has managed to spread his BAME-friendly food scheme across the border.

Starting with the one Sainsbury’s partnership in Coventry, his project extended to every Sainsbury’s in the city. They would receive between 40 and 80 crates monthly.

After sitting down on the steps of Churchill Way, Kervin asked a rough sleeper what provision there was for homeless people in Cardiff.

“He replied saying none,” said Kervin.

As a result, Kervin has managed to convince supermarkets across Cardiff to supply him with unused in-date food. Suppliers include Lidl, Morrisons and Aldi.

Cost-of-living obstacles

While the food pantry is thriving, it has also faced obstacles.

Butetown Community Centre tailors its items to its Muslim users. Buying both halal and non-halal meat is expensive but they are committed to prioritising their customers’ needs.

“We can’t buy both, so we only buy halal meat when budgets are tight,” Kervin explains.

The food pantry sources the meat along with fresh fruit and vegetables from a halal butcher around the corner.

Finding culturally appropriate items is not easy.

“Most supermarkets only allocate a tiny section for world foods. BAME food is scarce anyway, and this is reflected in our donations,” he said.

Kervin is also facing the challenge of competing with food waste apps like Too Good To Go.

“Instead of giving pantries all of their surplus food, apps like Too Good To Go take some. Aldi has even partnered with them which just directs the food elsewhere,” he said.

He added that Too Good To Go also disadvantages people who don’t drive, which make up a lot of his customers, whereas Butetown Community Centre is a central social hub accessible to people in the area.

On top of this, when he uses the Neighbourly app to book supermarket collections, he has to deal with competitors.

“In Coventry, I was one of the first people doing this. But here, I’m late to the game. Well-established food poverty projects like Cardiff Food Bank are given priority.”

Sometimes he turns up and the supermarkets claim they’ve already given the food away, so he avoids certain branches.

The pantry’s success

Butetown Community Centre’s food pantry is self-sufficient. Kervin says that all profits go back into the project.

They are thrifty, stretching their pandemic money from the council by buying long-lasting tinned goods that are still in stock.

“We’ve served as many as 75 families in a day when most pantries average 35,” Kervin proudly stated.

Since its opening, they have served at least 2,642 families.

There are currently five volunteers working at the community centre, but Kervin is paid.

His outreach efforts have previously earned him the Pride of Coventry award.

They are planning a cost-of-living event in early March, to highlight issues to the local councillors and review current food poverty policies. They are hoping to secure grants from the council.