In Pakistan, Raja Waseem has stood against the cement industries to protect the Katas Raj temple, its pond and the Kahoon valley from devastation. In an interview, he explains what he wants to achieve.

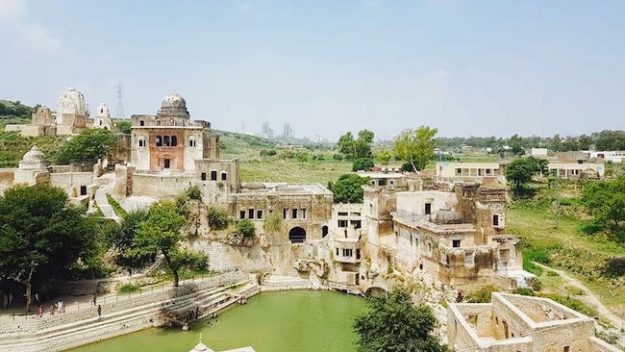

“Katas Raj temple is part of our cultural heritage and it’s our foremost responsibility to protect it,” stated Raja Waseem, a local inhabitant of Chakwal district from Mallot village. This village along with many others forms part of the famous Kahoon valley which stretches from Choa Saidan Shah to Kallar Kahar sub-districts in Punjab province.

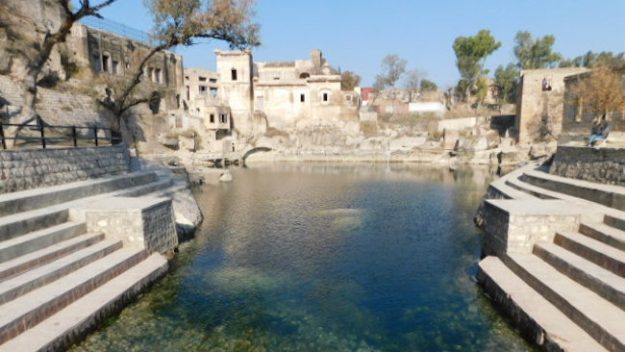

Kahoon valley has great significance, as it houses the Katas Raj temple and its sacred pond. Legend has it that this pond was formed when Lord Shiva cried inconsolably over the death of his wife Sati. The temple is considered as the second most sacred shrine in Hinduism and every year Hindu pilgrims from Pakistan and India visit the temple and bathe in it’s pond to seek forgiveness.

“In 2004, when the proposal to build a cement factory in Kahoon valley was brought up, we strongly resisted the move and told the high-ups that the Katas Raj temple and its pond would get affected, as the sacred pond might go dry due to excessive groundwater abstraction by industries. We also argued that being a rain-fed zone, the valley has limited water resources and groundwater extraction for cement production will reduce the availability of water for the local population. We also said that the air quality will get affected, as the dust particles will get trapped in the valley causing health issues among people,” he said.

The ordeal never stopped here, as things were about to get worse. Raja Waseem said, “To build the cement factory they needed land, which the locals weren’t willing to sell. So the powerful mafia lobbied with the government to acquire the land using the land acquisition act and manipulated with the revenue records to deprive the indigenous communities of their land rights. The matter was brought to the President of Pakistan but he was even misguided by the line-departments and nothing happened.”

He further explained how he along with other locals from Kahoon valley were pressurized to stop pursuing the cases in courts and sell their land for the construction of cement factories. “Police cases with terrorism clauses were registered against me and other locals and I was even barred from entering Chakwal district for six months.”

The cement factories’ construction was completed in 2007, and in two years the springs in the Kahoon valley began to dry up.

“My worst nightmare got real when the water in the Katas Raj pond diminished to alarming levels in 2012. The matter was taken to the Supreme Court of Pakistan but to no avail. In 2017, when the water of the Katas Raj pond dried, the Chief Justice of Pakistan took suo motu notice of the situation and then I submitted an application to become a party to the case.”

Raja Waseem single-handedly fought the case against the powerful cement mafia and appeared in the court to pursue the case in-person. He eventually convinced the Supreme Court of Pakistan that the water of the Katas Raj pond and the aquifer of the entire Kahoon valley has declined due to over-abstraction by the cement factories. “On court orders, the cement factory owners had to pay Rs. 2 billion (US$ 143.8 million) as security until they can find an alternate source of water. Other proposals included the construction of small ponds to harvest rainwater and preventing the Katas Raj pond from getting affected further and paying the provincial government for water that the cement industries use until then.”

“I won’t say it’s an amicable settlement but it is certainly a huge success in getting billions of rupees from a mafia that had defied the rights of indigenous communities in the every possible manner.”

Waseem recalled that when he was a kid, his parents told him to protect the Katas Raj temple and its pond because the pond had been supplying water to the nearby communities and fruit orchards for centuries. “The Katas Raj temple pond helped to meet the everyday water requirements even when there was little to no rain.”

“Today when the pond has gone dry, this calls for joining hands to protect our cultural heritage at the hands of unsustainable development.”

He also explained how on various occasions he was approached by the agents of the cement factories for an under the table deal but he always refused. “I just cannot breach the trust that the people of Kahoon valley have on me. The Katas Raj temple and its holy pond has to be protected at all cost,” he said.

The Kahoon valley is known for its roses, peacocks, wild sheep and loquat orchards. “I want the people of this country to realize how marvelous this area is, and to galvanize action to protect it from future threats,” added Waseem.

The people of Kahoon valley are coping with diminishing water levels and are forced to buy water from tankers, and breathing toxic air emitted by cement industries. The dust particles discharged by these factories later settle on crops and affect their quality as well.

“The decision by former governments to establish cement factories in the pristine Kahoon valley was a tragic mistake.”

“Although on the orders of the appellate court, the Katas Raj pond is now being recharged by artificial means but continued groundwater abstraction by cement factories would make it impossible to revive it naturally. The prolonged impacts include migration of the local populace to other areas,” feared Raja Waseem.

Raja Waseem’s struggle hasn’t ended yet. He has filed cases in the anti-corruption court against government officials for exercising undue influence on the locals of Kahoon valley to sell their land.

“It’s hell or high water. I will not bow before these people at any cost. My fight is to protect the Katas Raj temple, its pond and the Kahoon valley from further environmental deterioration.”