One of Cardiff’s smallest communities, the Tibetans, brought in the new year at the only Tibetan Buddhist temple in the city. What makes the Dzong special?

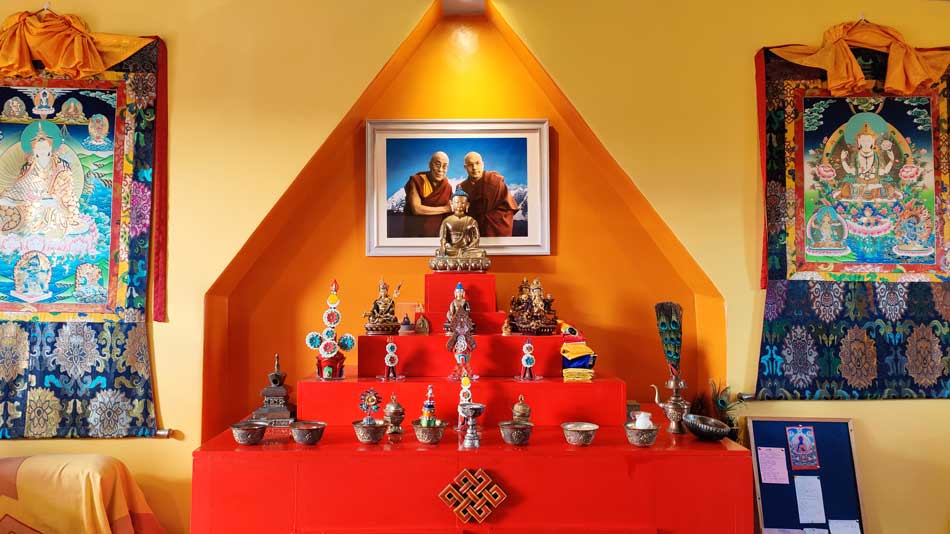

As you walk into a room, you notice the elaborate tapestries on the walls with scenes that you can only describe as other-worldly. There’s a faint hum of ancient chants, accompanied by the chiming of resonant bells. Just as you start taking it all in, a pleasant aroma of jasmine flowers from the incense sticks rushes over your senses when you see a beautiful bronze idol of the Buddha.

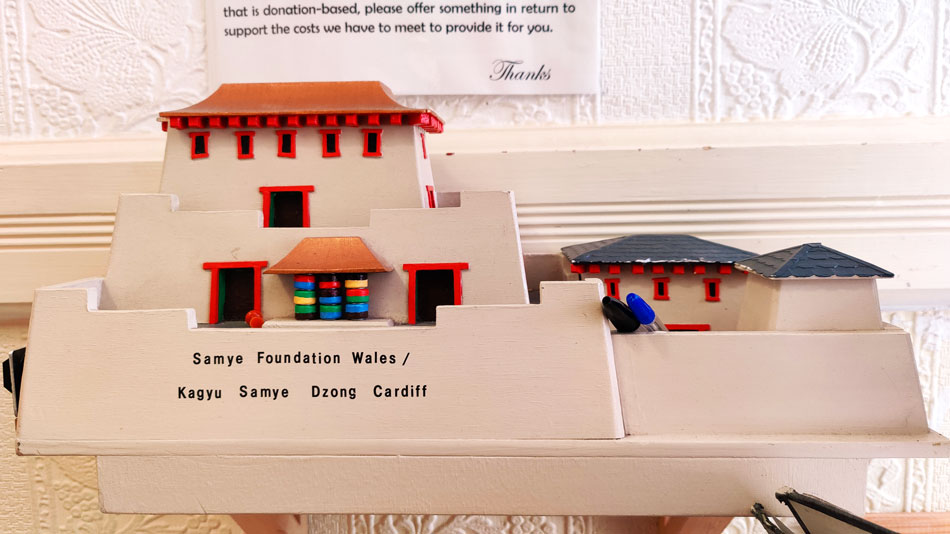

If you are picturing the prayer rooms of gigantic monasteries of Tibet, with their tall wooden parapets and majestic strokes of red paint, you would be wrong. This small terrace house, less than a ten-minute walk from the Taff river in Canton, seems like an unassuming building in the suburbs. But inside, you may find the closest thing to Nirvana on this side of the Severn. This house is a dzong, a Buddhist meditation temple.

The 15-day celebrations for the Tibetan new year, Losar, are in full swing for the 22-resident strong Tibetan community of Cardiff, with the Kagyu Samye Dzong standing as a reminder of their homeland 5000 miles away.

“At this time of the year, everything is about joy and people coming together. We try to keep our minds pure,” says Lorraine Harris, one of the founders of the Kagyu Samye Dzong.

Lorraine and Anthony Harris founded the Kagyu Samye Dzong on Cowbridge Road in 2015 to preserve Tibetan Buddhist culture and spread the awareness of Tibetan meditation techniques for mental wellbeing. Lorraine has been working as a mindfulness trainer and a meditation teacher for more than 25 years, but her contact with Tibetan Buddhism is much older.

Lorraine has witnessed Tibetan Buddhism grow and spread in the UK and has visited India several times to meet the great lamas. But the journey of creating the wellness centre and temple in Cardiff was not easy. “We have been running the Kagyu Samye Dzong for 40 years,” says Lorraine.

The organization was set up first in Durban, South Africa in 1981 with the blessing of Akong Rinpoche, a leading figure of Tibetan Buddhism and the founder of the largest British Tibetan monastery, Samye Ling, in Scotland.

Akong Rinpoche instructed Lorraine to establish a dzong in Cardiff as well, but the lack of funds was an issue. “We started in an attic in Caerphilly, then we moved on to hiring different places and centres in Caerphilly and Cardiff. We didn’t have much money,” says Lorraine.

But soon, Lorraine and Anthony’s good karma came to their aid, when they received three donations worth more than £45,000 in total. “Two of our group members went to Nepal to meet Thrangu Rinpoche, my root teacher. They took a map and asked ‘where should the centre be for Kagyu Samye Dzong in Cardiff?’ He drew a circle on the map, and years later we realized the building we ended up buying was in that circle,” says Lorraine.

Lorraine has also helped several Tibetan refugees find a footing in Wales, especially after the persecution of Tibetan monks and people began in China. The dzong acts as a spiritual centre for the city’s Tibetans, where they can pray, meditate, celebrate and remember their ancestral homes together.

“It’s a time of renewal,” says Gelong Thubten, a Buddhist monk who has worked with the Tibetan community since childhood and the director of Samye Foundation Wales. “In the days leading up to Losar, we do a lot of prayers to burn away the negativity of the previous year and purify anything that has been challenging or difficult.”

Tibetan Buddhism has a Karmic base, which has an influence on Losar’s prayers, says Gelong: “We cross into the threshold of the new year with a sense of hope, inspiration and courage… most Buddhists practice a lot of meditation and prayer… the benefits of what we do during these days are multiplied many, many thousands of times.”

The two most significant prayers of Losar are called ‘Pujas’ – Puja being the Sanskrit word for worship. One of them is dedicated to Guru Rinpoche or Padmasambhava – the Buddha who brought Buddhism to the Himalayas and the Tibetan plateau. This Puja is recited to dispel obstacles during difficult times. The second Puja is called the Green Tara Puja or Sgrol-Ijang. “The Green Tara Puja is about removing fears… which is very important in the time that we live in,” says Lorraine.

After the Green Tara Puja, the devotees shared and ate Tsok – offerings of vegetarian food made to the deities. An essential part of Tsok is a cake called Torma which is prepared with either oats or flour, kneaded with butter and dry fruits. The Torma we had was made with oats, peanut butter and bananas; usually, the Torma is prepared with all kinds of ingredients brought by the devotees.

The Tsok was followed by a meditation session in the shrine room, where the devotees meditated while chanting the Medicine Buddha or Sangyé Menla chant. While the Guru Rinpoche and Green Tara pujas are to dispel obstacles and fear, this chant is used to invoke the powers of healing and peace. The atmosphere was calming and reminded me of the time when I celebrated Losar at the Thicksey monastery in Ladakh, a part of northern India dominated by Tibetan Buddhism. The harmonious chanting of everyone sounded just like the chants of lamas echoing off the wooden walls of the large monasteries in Tibet itself. The meditation lasted for about an hour and everyone left the shrine room at peace with themselves.

While these prayers may sound like they are dedicated to God-like figures, Gelong reminds us that Buddhism doesn’t have any Gods. “The whole idea is that these deities symbolise the purity that is the base of all reality. We believe that all beings have a pure mind deep down inside, which is the meaning of Buddha. So we cant view Buddhist deities in a dualistic way that they are sort of gods in the sky… we try to view them as aspects of the mind that we can relate to in order to get closer to the truth,” says Gelong.

Since their escape, the Tibetan refugees and their families have adjusted well to life in Wales and have formed a strong bond in their community. “The number of Tibetans are growing in Cardiff; they very much tend to keep to themselves, but they have lots of luck, they all have jobs here, which is brilliant,” says Lorraine.

“I was here with the very first Tibetan refugee in Cardiff called Dicky. She escaped China – well they call it China – because they were after her for putting up pictures of the Dalai Lama,” says Lorraine. Dicky first arrived in Southampton and moved to Cardiff after Lorraine offered her a place to live at her house in Splott. A lot of other Tibetans had also fled from Chinese persecution of monks, like Lama Lobsang who escaped to Cardiff in 2007 following six years of torture in a Chinese prison. Some Tibetans in Cardiff have also founded the Cardiff Tibet Group, an organization that spreads awareness about Tibetan culture and self-determination.

While the number of Tibetans in the city grows slowly but steadily, the Kagyu Samye Dzong remains the only public place of worship for them, but as the popularity of Buddhist philosophy and well-being techniques also increases, we may hope to see more of these dzongs in the future.