Persian LGBT+ Asylum Seekers are having a meet-up in Cardiff next week. How hard is it being an LGBT+ asylum seeker in the UK?

When Mehreen, a university student in the UK, came out as a lesbian to her family in Pakistan, they threatened to kill her for ‘committing a sin.’ Back home, she was pressurised to marry her cousin. The punishment for being a homosexual in Pakistan can be life imprisonment or even death.

“When I told my family the truth, they threatened to kill me. If I go back, they will do it in the name of honor,” says Mehreen who now lives in Cardiff as an asylum seeker in shared accommodation.

She is waiting every day for an answer that could change her life, but the answer is yet to come.

Her asylum status is currently under appeal after her initial application was rejected. “The process is exhausting. You live in uncertainty, not knowing if you’ll be sent back to a place where your life is in danger,” says Mehreen. “My life would never be truly mine. I had no choice but to live and seek safety somewhere.”

Mehreen is not an isolated incident of LGBT+ person seeking asylum in the UK. According to UK Home Office Report of 2023, 2% of asylum claims in the UK included sexual orientation as part of the basis for the claim with a grant rate of 62% down from 73% in the previous year. Asylum seekers from Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Iraq, Iran and Uganda constituted a major chunk of the LGBT+ Asylum seekers in the UK.

Mehreen, however found strength after connecting with the Persian LGBT+ Asylum Seekers Organization, led by founder Mazyar Shirali. A victim of ethnic discrimination himself, Mazyar created the organization in 2012 to assist others. The organization, despite its title, is open to all people and identities.

“It’s not about making asylum easy. It’s about making it fair,” says Mazyar, 40 who came to the UK along with his family as an asylum seeker in 2001. He traversed across countries in flights, lorries and on foot due to the political turmoil in his country.

Alma, a bisexual who came from Botswana after recovering from severe injuries which were caused due to an assault by her boyfriend when he came to know about her sexuality is also a member of Mazyar’s organization. She says that she cannot go back to her country because of the issues with her family.

Along with resistance from the family, homophobia among asylum seekers’ community and ignorance from the authorities and the system is prevalent. “Some officials don’t even know what LGBT stands for, let alone how to assess an asylum claim fairly,” says Mazyar. “Imagine having to sit across from a Home Office officer who asks, ‘When did you decide to be gay?’ or ‘Can you prove you’re gay?’ How do you answer that?”

Many struggle to talk about their identities because they come from cultures where such discussions are taboo. Mazyar says that such people often lead a dual life in their countries. “A person with two children, a wife, and a family back home may come here and finally feel free. But for someone who has never lived this experience, it is difficult to understand what’s going on in their mind.”

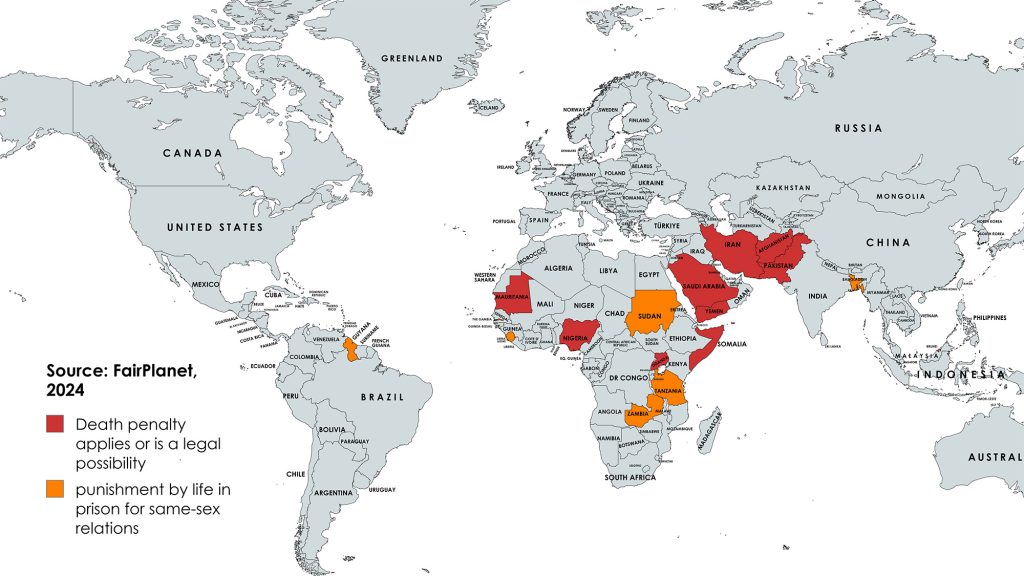

Mazyar says that by rejecting an LGBT+ asylum seeker’s case, they face deportation to a country where they could be imprisoned, tortured, or killed. Asylum seekers from the LGBT+ community often face harsh imprisonment or death penalty in their home countries . “When asylum seekers get refused, it’s not just a legal issue, it’s a safeguarding crisis. Their lives are in danger.”

While awaiting asylum decisions, many live in shared government housing often facing discrimination from housemates. “You escape one kind of discrimination only to face another. It’s exhausting,” says Mehreen who is often criticized for her ways of cooking, cleaning and dressing. “There are people from certain countries who don’t see Black people as equal. They treat us as dirty, as less deserving,” adds Alma.

Asylum seekers in the UK are paid £49.18 per week and they often find it difficult to get a job. Mehreen says that she lost her right to find a job when she applied for asylum, and she has to work in an exploitative work environment to support herself where she is paid almost half the national living wage. “I used to have ambitions, career goals. Now I just think about how to survive the next month” she says.

Shahrukh(name changed), an asylum seeker who is gay and from Pakistan tries taking a different path by not choosing to live in asylum house and find a full time job instead. He is jobless for several months now. “If we were granted asylum, we would have opportunities for full-time jobs. But right now, we are just stuck, waiting, and hoping,” he says.

Organizations such as the Persian LGBT+ Asylum Seekers organization help stranded asylum seekers such as Mehreen, Shahrukh, Alma and hundreds other. They help the members find counselling, therapy and legal support thus acting as their family in the UK.

Mehreen says that everyone in the community needs to learn about each other, be family, and create bonds. By listening to other people’s problems and helping them, she gets a sense of belonging. “This is the first time in my life I feel safe. It took 34 years, but I finally feel like I belong somewhere.” Shahrukh adds, “When I felt alone, rejected, this organization became my family. It connected me to people who understand my struggle.”

Mazyar’s organization is holding an event in Cardiff on 14 March where they are expecting lots of good things. He says that they have become a family now, and this event is an opportunity to meet new people from every part of the country. “Now, many organizations are becoming more diverse and accepting members from different backgrounds. This is what the rainbow is about – every colour, inclusivity under one umbrella.”