Patrick Jones travelled to Palestine, where he witnessed people living under occupation. His poems capture the experiences and sorrows of Palestinians.

As the boy threw the frisbee, a smile appeared on his face for the first time that morning. Patrick Jones didn’t understand his words – he knew only a few in Arabic – but as they threw the plastic disc between them something seemed to lift in the boy’s spirit. This moment remained with Patrick after his visit to a Palestinian home.

The boy’s mother invited Patrick to their home for some watermelon and to share their experience of life under Israeli occupation. The Welsh poet was here to find inspiration for a series of poems that he has published in his poetry album: A Constellation of Sorrows.

“That was a very precious moment, I wondered what the boy’s future would be like with such terrible oppressiveness. But the people in Palestine, I have to say that they are very resourceful. Sadly, they have to make the best of the situation. It really shouldn’t be like that,” says Patrick.

He wrote many poems in Palestine and continued writing after returning home. He recorded the stories of civilians living through the Israel-Palestine war and his own thoughts. At times, he felt anger, but in the end, he chose to turn that anger into poetry.

“There’s a track on my album called Khalas, which means enough in Arabic. It carries a firm sense of finality, and that is exactly how I feel. It’s enough, we have one world, and people need to be treated equally and fairly, but when we look around the world, the reality is different,” says Patrick.

He remembers listening to stories by Palestinians, stories that have been passed on through generations. But many of them do not have the means to tell those stories to the outside world.

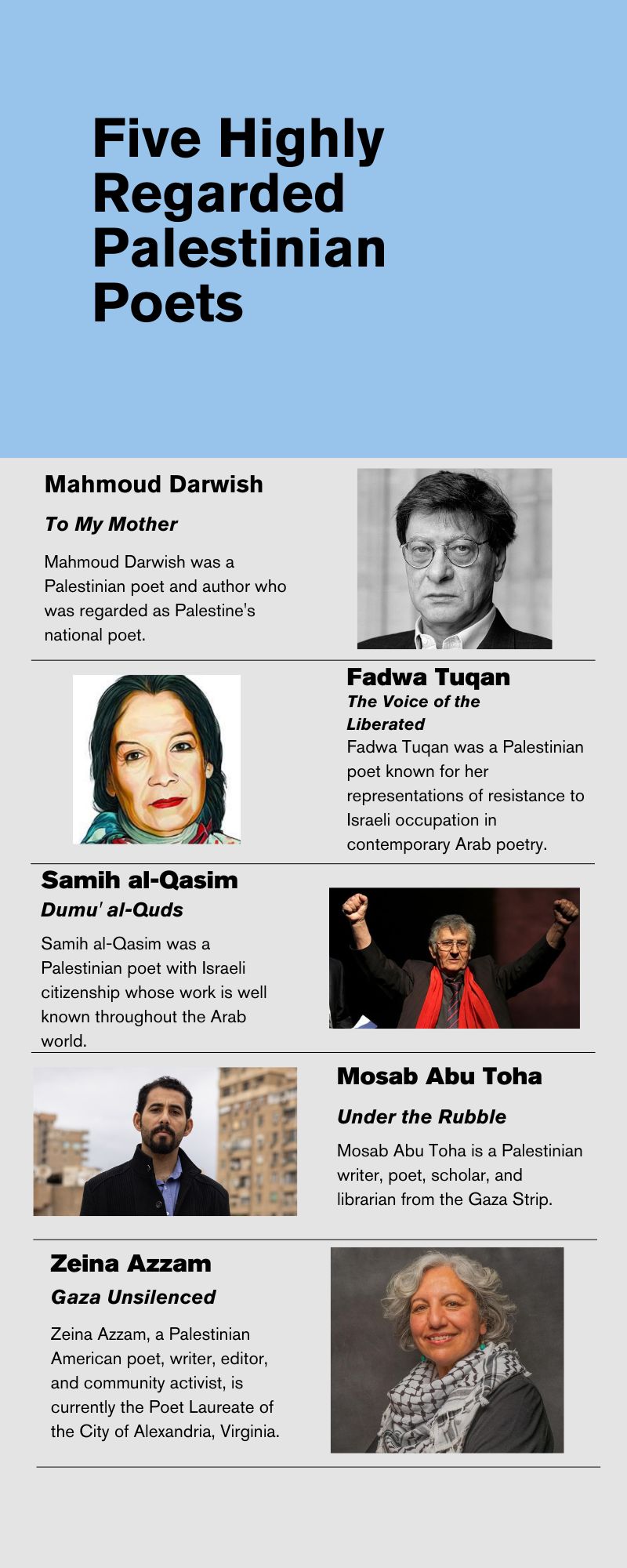

“We met many Palestinians and heard their stories. It’s so sad that Palestinian poets in Gaza and the West Bank, especially in Gaza, they have so little to write on. It may be their phones, as they don’t have computers, and even basic things like pens and paper. Yet, they continue to write, trying to bear witness,” says Patrick.

What is portrayed in the news does not truly represent the situation in Palestine, according to Patrick.

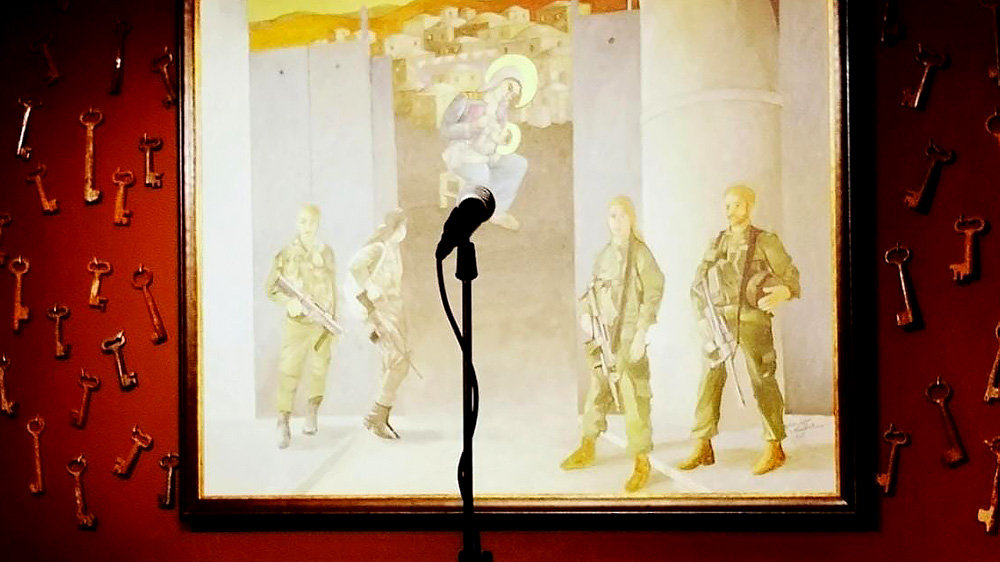

“There are Israeli soldiers maintaining order on the roads, telling you which path to take. Checkpoints are placed every few kilometers, there are sniper posts on the roads, and surveillance cameras are on every street. People live in a tense environment,” he said.

“We were just cleaning up the garden, then we heard that the military went to another house, where the other volunteers were helping to clean, and told them they had to leave because of a security concern. So, there was always this fear of being watched and being told to leave. It was like a kind of silent oppressiveness,” says Patrick.

In the occupied areas of the West Bank, Patrick saw another side of life within this environment of control. Palestinians live under Israeli rule, but they have not been consumed by hatred.

“I think that was the most heartbreaking part, but also the most humanised part because these people had no hatred. They didn’t want to see Israel destroyed. They just wanted to live in equality and peace,” says Patrick.

Patrick believes Palestine has a rich history of poets and poetry is highly respected as an art form in Palestine. He visited a museum dedicated to Mahmoud Darwish, regarded as the national poet of Palestine, in Ramallah.

“Poetry and art are highly valued in Palestine, and poetry is deeply respected as an art form there. On the contrary, we don’t have any museums dedicated to poets in Wales,” says Patrick.

But in the war, art and poetry face the threat of disappearing. Patrick believes the Israeli police doesn’t care how much Palestinians love art, as art space like bookstores in the West Bank are at risk of police raids.

“We went to a bookstore in East Jerusalem owned by a Palestinian. It was a wonderful bookshop with poetry books, history books. But I heard that the Israeli police raided the bookshop and removed many books,” says Patrick.

The two weeks in Palestine made Patrick realise something. He used to get angry and argue in response to others’ remarks, those unfriendly comments about Palestinians. But after witnessing suffering there, he ignores those comments. “I used to want to argue against people’s comments, but now I try to ignore them and focus on my writing instead. What I witnessed there stirred my sense of humanity, I think I have to be a good person,” says Patrick.

Looking back on his time with the Palestinian people, Patrick feels that only by being in such a struggling environment can one truly understand the hardships and pain of ordinary people in a war. He believes that Palestinians only want a peaceful and equal life, but even this simple wish seems out of reach. He wrote a poetry album about his journey in Palestine to show people what it is really like there. It is not a place of terror, but a place where people are longing for peace.

“Some people kept saying that all Palestinians are terrorists, and I told them, you have no idea. Every single person we met just wanted to live with love and equality,” says Patrick.