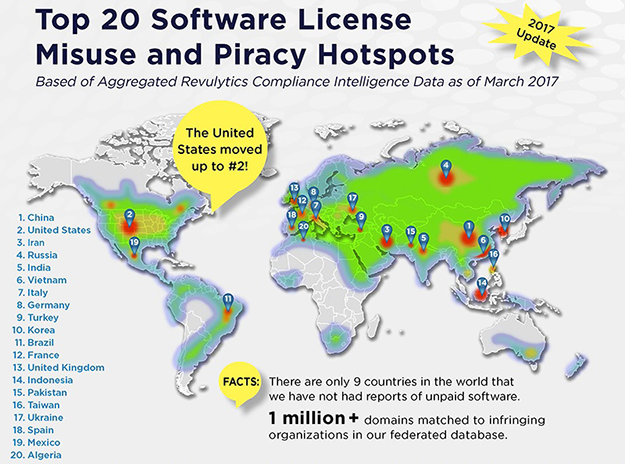

More than half of web users* admit to downloading pirated software. Do they risk ending up in court?

We’ve all been tempted to do it. You need a copy of Microsoft Office, or of Photoshop, to work on your assignments, but the price tag is just horrendous – you can’t afford to spend hundreds of pounds. Surely nobody will get hurt if you find your way around it on… “alternative” channels?

Cue torrent sites – the speakeasies of the internet. “How amazing,” you think to yourself, “that these people, these ‘pirates’, should remove limitations from software and make it freely available to all! I wonder, what drives them…?”

Though the thrill of the challenge is the main motivator for some “crackers”, not everybody is so innocent in their intentions. “Sure, [some do it] for the kudos, for reputation, advertisement,” says Tony Crampton, of Cardiff-based copyright specialists CJCH Solicitors. “[However,] it could also be for a sinister end, because anyone who uses software that isn’t genuine is opening up their system into all sorts of vulnerabilities.”

“History shows that every time people tried to impose restrictions, [there were others] trying to end those restrictions,” Crampton says.

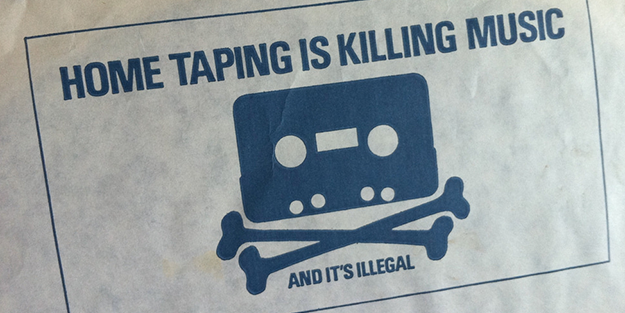

He’s not the only one to think so. For digital rights advocates Open Rights Group, the issue around copyright is decades-old: “I don’t think [the internet] created this situation,” says executive director Jim Killock. “If you look at… things like the rise of taping technologies, photocopies, video tapes… all of those, I think, started the trend towards a much easier situation for people to casually infringe copyright, on a user-to-user basis.

“I think there’s been a widespread culture of informal copyright infringement for several decades prior to the internet… If you look further back, you can actually see much more relaxed attitudes towards copyright – particularly in certain artistic circles – than perhaps we have now.”

Nevertheless, there’s a fundamental difference between the physical and digital “shoplifting”. Interestingly, companies are not concerned with end-users so much as with commercial actors who distribute the cracked software: “If I don’t get revenue from products, then research and development goes down, and there’s no product,” Crampton says.

CJCH Solicitors specialise in non-compliance by “infringing users”. These users remove licensing protocols in order to resell the software illegally, and make a personal profit. Sometimes it’s even the businesses themselves that manage to do it, to save on corporate licences.

However, if there’s an offer of pirated software, it means that there’s a demand as well. For Killock, the companies have a bit of self-critique to make: “The companies may regard this sort of behaviour as shoplifting. We would regard it firstly as a market failure … and as an activity often probably akin to home taping [where songs airing on the radio would be recorded on cassette tapes].

“That’s not to say there is not a potential impact on revenues, but [it’s] on them – the rights’ holders – to correct the market failure before they start blaming end-users.” He reckons there’s been a shift in what users expect to be able to gain legally. Since digital distribution is so easy and cheap, when something isn’t available – in certain geographic areas, for example – users want to know why.

In any case, in matters of copyright, pragmatism takes precedence over a rigid application of law, as Crampton explains: “There’s got to be a reasonable application of the judicial process, and if it’s just a single person, with a single case, is that in the interest of the company to sue? There must be a formal negotiation to move forward… I would always go for negotiating a settlement on the way through. Jail would certainly be the last option.”

Again because of pragmatism, it’s up to copyright owners to push for enforcement, Killock says: “The way it’s meant to work is that the costs of enforcement are borne by the copyright holder, [so that] actions that are taken are proportionate to the potential losses. [W]hile there has to be a mechanism for copyright owners to enforce, there also has to be [an] economic advantage [in doing so].

“That’s kind of built into the way copyright functions – or is meant to – and it’s quite an important principle, because the minute you start moving copyright enforcement from the private actors to state authorities, the incentives become distorted, because the state… can spend well over what is necessary and it can spend it on the wrong things, [targeting] the wrong sorts of people… for public or policy reasons, rather than economic incentives.”

Killock reckons that the focus has generally shifted towards commercial actors, and he sees it as a good thing. “If end-users got targeted,” he adds, “that’s when we would get worried.”

*Data from BSA Software Alliance, a trade group founded by Microsoft.