As LGBT+ history month has ended, a question is still begged: Is the UK inclusive enough for LGBT+ refugees and asylum seekers?

Numair Masud was privileged in many ways. He was raised in an upper-middle-class family in Karachi, Pakistan. He passed A-level exams in his home country and then studied zoology at the University of Bristol. Currently, he is a final year PhD student researching animal welfare at Cardiff University.

But one thing has repressed him through his growth. He is a gay man, but he couldn’t talk about it openly otherwise he would be imprisoned for life or even be killed.

Pakistan’s Penal Code Section 377 criminalises the sexual intercourse between men with a maximum penalty of life imprisonment, while Hudood Ordinance following Sharia law principles imposes harsher penalties-stoning the gay couples to death.

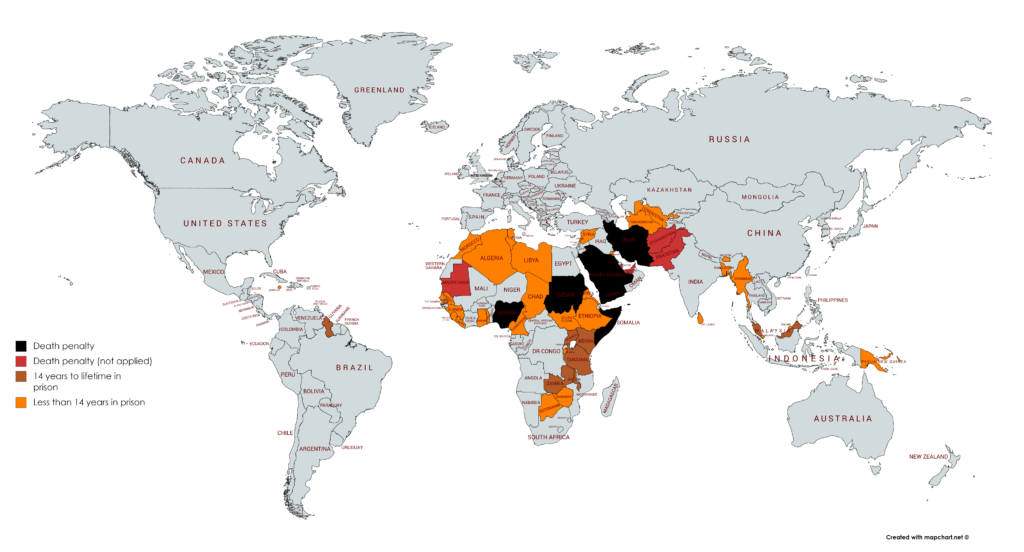

At least 68 countries criminalise consensual same-sex acts

“I don’t know how to express that (gay identity) because I never had any practice doing that in Pakistan, so I did struggle to come to terms with that,” said Numair.

He used to avoid being judged by people, either in terms of being BAME (Black, Asian and minority ethnic) or being a sexual minority. “I’m this island and I don’t need to operate on the labels. I can just operate under this vague enigma of Numair.” While tasting freedom in the UK, he had barely anyone to share with.

He said he didn’t feel the need to shout from the rooftops and reach out to the community. But at the end of his undergraduate degree, he realised that he didn’t have a single friend in the UK.

While applying for his master’s degree, he decided not to confine himself anymore. He downloaded Grindr, a dating app designed for gay men. “I did develop a thicker skin and I learned to take more rejections. I learned to take more unusual comments about the colour of my skin or about the way I look.”

He started to meet people and make meaningful connections with them.

Now, he has found his community, engaged in LGBT+ activism, and claimed asylum which means he is granted equivalent rights to live and work as UK citizens.

He is one of the lucky guys among the LGBT+ immigrants in this country.

“The Home Office does not believe you’re gay”

The Guardian revealed that the Home Office has declined at least 3,100 asylum claims from LGBT+ nationals from countries that criminalise homosexual behaviours. LGBT+ asylum seekers have to prove their identity to the Home Office and immigration court, and the process could be disturbing.

“The Home Office does not believe you’re gay. He said you do not look too gay. You can be discreet in your country. He said that to my face. I was a mess when I found out my court was in a month later. I was emotionally suffering. My court was successful but it was horrible to be interviewed about my sex life in front of a judge.” Ourania Vamvaka, a Cardiff University researcher, quoted one of the informants in her study of LGBT+ immigrants in South Wales.

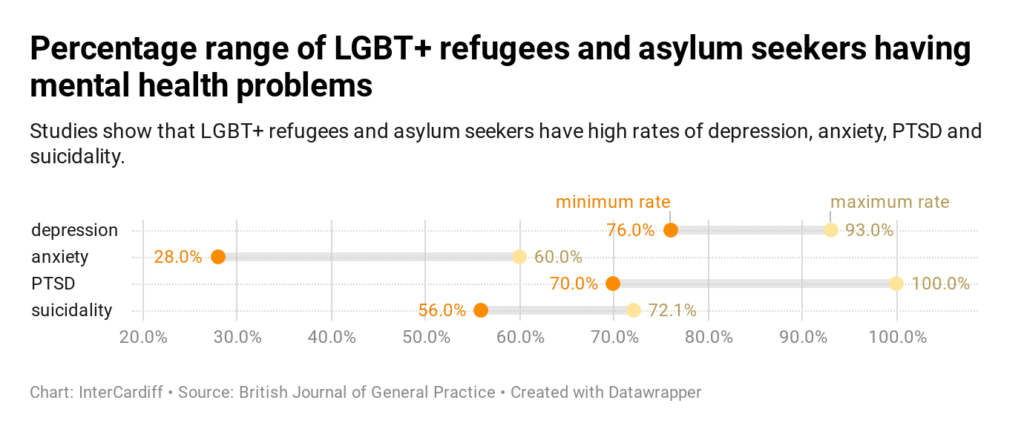

“This is a particularly prevalent struggle for LGBT asylum seekers as they are justified of their sexuality by narrating their deeds,” said Ourania. “Those narratives of proof become particularly challenging for those who have experienced sexual violence assault and torture and may struggle with depression.”

Apart from the difficulty of applying for asylum, LGBT+ immigrants lack a safe place to tell their stories. Ourania also mentioned the homophobic sentiment around LGBT+ immigrants’ accommodation which intimidates them to express their identity. A participant in her study said: “I came to the UK to be free and be myself. The moment I entered the house I was back in the closet.”

Even within the LGBT+ community, refugees and asylum seekers, who are usually BAME as well, are the most discriminated. Being a refugee, Numair said the label always comes around him. “Whatever you view yourself, the image of a refugee in our world today is never positive.”

“We fought for years and years to not being labelled as facts and a square, not being labelled as feminine and unnatural,” said Numair. “We’ve fought against labels all our lives and then we create new ones. In theory, we are united, but in practice, we’re not.”

Working as a part-time LGBT+ activist, Numair went through case files of asylum seekers and attested to them in the immigration courts, though he said the process could be time-consuming and emotional.

He also works actively in Glitter Cymru, a monthly social meet-up group for BAME LGBT+ people. He is trying to create a safe place for those people to share their experience and find others.

“We often think our story is the worst or we’re the centre of our universe, but there are other universes out there. If you don’t discover them, then you’re just a lonely universe,” said Numair. “A big part of healing is being able to relate to other people’s suffering and realizing you’re not the only one suffering and you’re not the only one who’s lonely.”