UK government banned contract cheating in 2022 but essay mills are still everywhere. How do they work, and how can academic honesty be upheld?

In August last year, Sanjana Srinivasan was frantically shopping for woollens, boots and Indian spices. She was going to Cardiff for a master’s degree in less than a month. Amid the kerfuffle of last-minute packing and advice from her mother about how to survive the cold, wet UK weather, a message popped up on her Instagram. They promised distinction in every essay and A+ grades in assignments.

The 25-year-old still wonders how and why she was targeted.

“They knew I was going to study at Cardiff University and promised they could get me a distinction,” Srinivasan remembers. “They said they offer free plagiarism and AI [Artificial Intelligence] checkers too.”

In the six months since, Srinivasan has been approached by countless accounts on social media offering similar services. She is not alone. Thousands of students across the UK are subject to messages trying to convince them to get assignments, essays and theses completed for money, a practice often called contract cheating.

The UK government introduced a law in April 2022, making it a criminal offence. Their advertisements were outlawed, and internet service platforms were asked to crack down.

Yet, three years after the legislation, contract cheating is common in universities and companies producing assignments for money are everywhere.

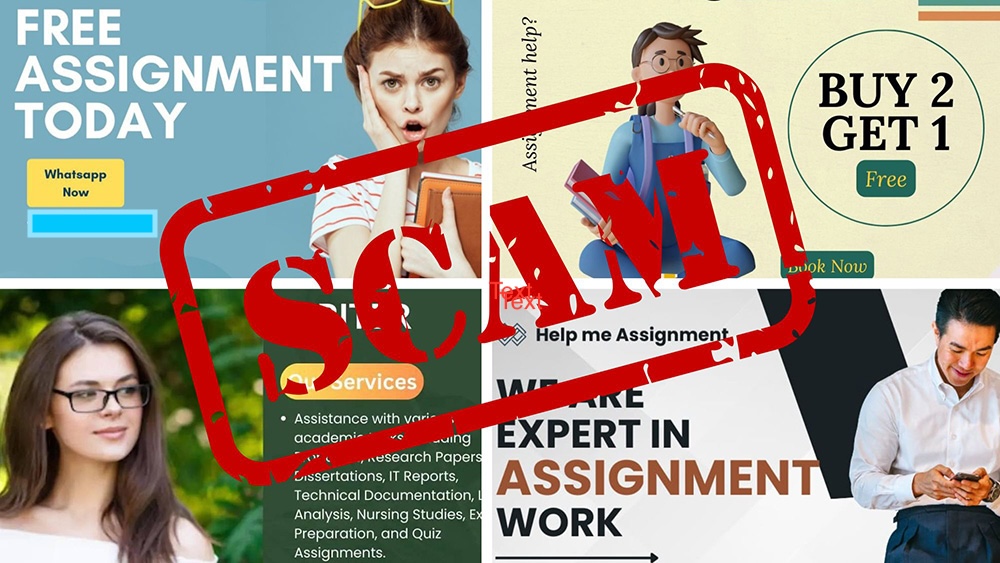

A mix of seductive messages, fake profiles, sham testimonials and promises of distinction are being used to lure vulnerable students. Often, cheaters are caught. Occasionally, they are expelled from universities.

InterCardiff found that students’ groups on Facebook and WhatsApp are littered with posts from companies offering special discounts on festivals and holidays: 20% off on Valentine’s Day and buy-two-get-one-free on another occasion. Websites offer live price quotes — a 7000-word Economics thesis on ‘Developing World and Tariffs’ can cost over £330.

A firm, claiming to be the world’s best essay and assignment help company since 2007, has testimonials and pictures of academic helpers. A man featured on its website is identified as Ricardo Hunt, a PhD in English from Oxford University. However, Google image search, a tool to search images online, reveals that the man is Eric Johnson, an academic in the US.

On the same website, Michael Johnson is listed as a lecturer, doubling as an assignment helper. However, he turns out to be an entomologist, Jeffrey White. He has been featured on the US chat show Dr Oz.

A Facebook profile named Olivia Adelaide told InterCardiff they work for an academic writing company based in London. Adelaide shared writing samples with us after we expressed our doubts about using their services. While the assignments were mediocre, they came with students’ testimonials, stressing they were awarded distinction or high marks.

Shahid Ali (name changed), 27, runs a firm in Mumbai, employing around 50 writers and churning out nearly 60 essays every week.

Companies like his are called essay mills. They churn out hundreds of assignments every week.

Fresh from a vacation in Thailand earlier this month, he says, on the condition of anonymity, most of his essays go to UK universities.

“We have dedicated teams for every subject, and the work is assigned based on our writers’ specialisation,” he says proudly. “The regulars get a monthly salary of around £180 to £220, depending on their work. The freelancers are paid based on the number and quality of their essays.”

Ali guarantees that the essays by his writers are of stellar quality and plagiarism-free.

Thomas Lancaster, principal teaching fellow at Imperial College London, says these companies look for new and vulnerable students on social media and befriend them through fake profiles. When students struggle academically, they offer to put them in touch with firms that can help write their assignments.

“Sometimes these firms ask students [who used their services] about others in the module,” says Lancaster, who has researched contract cheating for over two decades. “Sometimes, they log into the learning software of a university using credentials of those they have helped. And when they log in, they can find information on other candidates and gently expand the range of possible buyers.”

Often, the targets are non-native English speakers who find writing lengthy academic essays challenging.

Nick Mosdell, an academic misconduct coordinator at Cardiff University’s School of Journalism Media and Culture, estimates that on average, he comes across 10-30 academic misconduct cases each year, and nearly two-thirds of those students are foreign.

“They prey on students who are stressed, students who don’t particularly want to be on their course, students with language issues and students who are not particularly familiar with the territory they are in,” says Mosdell.

While the exact figures are hard to get, estimates suggest around 5% of students have used these services at least once. Often, the companies are based in countries outside the UK, with India, China, Pakistan and Kenya proving to be the most fertile grounds. Their locations make them immune to the UK law.

But the use of these services is a slippery slope, leading to blackmail, extortion and harassment.

Mosdell witnessed a case last year when a professor was concerned about an assignment because the writing style did not fit the student. While the lecturers were still deliberating, the person who wrote the essay contacted the module leader, claiming the student had yet to pay him.

“Ironically, he said it was unethical for the student not to pay him. So, we did some digging around, and the person turned out to be genuine. The student’s denial was preposterous, and he was made to resit the assignment for a capped mark,” Mosdell says.

So, how can universities combat essay mills and uphold academic integrity? Mosdell and Lancaster advocate making assessments more creative, reflective, and interesting.

“Make these essays timely so you are not critiquing a theory from 1984, you are critiquing how that theory applies to something that happened last week. It is something very straightforward to do. And these discussions are happening across the sector,” says Mosdell.

Meanwhile, Ali acknowledges that his business is not strictly legal. But there is little fear of trouble as the demand for the essays continues to surge.

“See, I have to earn something, I don’t come from a rich family. These days, there are several other methods to cheat… Yet, we have established trust with students, and, for now, business is booming,” he says.