The sun never sets on the British empire – but then why are Britons made to stay in the dark about it?

In March this year, hundreds of protestors gathered outside of South Wales Police Station in Cardiff to protest against the killing of Sarah Everard, rising hate crimes against people of colour, police brutality and a draconian bill – Policing, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill (PCSC) proposed by the government which the citizens believes is a crackdown on human rights and civil liberties.

Similarly, last June with the global Black Lives Matter movement in Bristol, protestors gathered around and chanted “Pull it down” to undo mistakes of the past and proceeded to tie a rope around the statue of Edward Colston – seventeenth-century slave trader on whose watch more than eighty thousand Africans were trafficked across the Atlantic.

Tom Oliver Berry, a 23-year postgraduate student at Cardiff University said that “It’s critical to learn about British colonialism since it would promote young to people think critically of their country. I think recent events surrounding the removal of statues and many people second-guessing why we glorify past British figures have opened many eyes to Britain’s darker history.”

Although the mention of the empire is on the curriculum – as Key Stage 3 history curriculum aims to provide “gain a coherent knowledge and understanding of Britain’s past and that of the wider world.” The growing academisation of British schools means that most schools aren’t required by law to teach colonial history.

The failure to teach colonial history and including works of non-white authors within the teaching sphere gives a narrow understanding of modern diverse society and further perpetuates a negative feeling towards others.

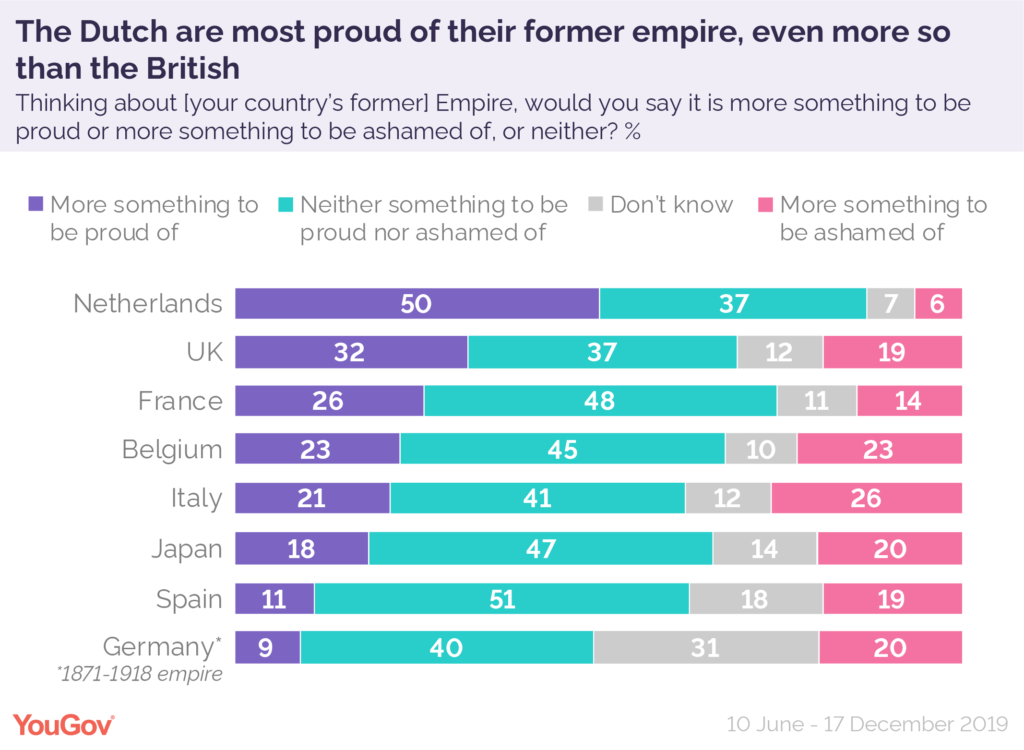

A 2020 YouGov poll reveals 30% of Britons believe colonies were better off as part of the British Empire.

The nostalgia for the empire further reveals that about a third of them believe that colonies were better off being a part of the empire, with almost 27% wishing Britain still had an empire.

This comes in contrast to Germans, who on the same poll were least proud of the empire, popularly known as ‘the Second Reich’ – the period from 1871 to 1918.

Tara Cheetham, a 19-year-old Cardiff University students feel extremely disappointed about the lack of inclusive curriculum, saying, “It is frankly disgusting that the British education system excludes colonial history from its curriculum. I think a lot of British people are ignorant about colonial history because of a lack of education regarding it or being ashamed by it.”

Adam Price, leader of Plaid Cymru in an opinion piece wrote, “Wales must liberate itself from its colonial past. But that means not just liberation from its own history of subjugation, but its history as subjugator too. Wales’ experience of privilege and powerlessness is not a simple binary but a complex relationship.”

Dr. Ben Curtis, a historian of South Wales said, “I’d be extremely wary about drawing any direct parallels between Wales’s experiences and the experiences of countries elsewhere around the world that were colonised by the British Empire.”

However, Rabab Ghazoul, a Cardiff based Iraqi artist in a piece for Welsh independence wrote, “ Being both victims, and beneficiary of colonialism, means we have in Wales a rare capacity for both radical empathy and radical responsibility. It’s from this place of dual experience, that we can unlock truly emancipated futures.”

Ben believes that teaching the next generation about the history of not just Wales but the contribution of people of colour to the country would be able to provide a sense of empathy in young minds and go a long way to fight instructional racism and discrimination.

The research by YouGov reveals a pattern of the education system which failed to educate the British public about the brutality and cruelty of the empire and its relationship with present racism in Britain.

The government argues schools “have the freedom and flexibility… to teach pupils about the history of Britain and the wider world. This can include the topic of the British Empire”. Schools shouldn’t have the option to ignore this pivotal moment in British history

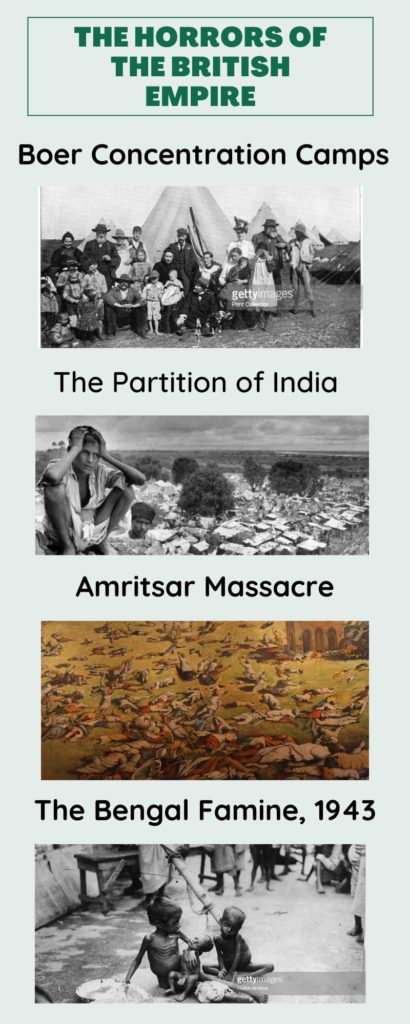

Growing up in India, our curriculum never addressed the casteist attitude of Gandhi. It conveniently missed out on teaching us why he thought it was important for Hinduism to have a caste system and why Dalits will never be treated as equals. Similarly, the British curriculum creates an image of Winston Churchill as a wartime hero – which he might be, but it fails to mention his role in the Bengal Famine which led to the death of over 3 millions Indians.

However, it isn’t just the school curriculum that needs to be amended. At the university level, a look at modules offered by Cardiff University for a MA in History course fails to offer a single module that focuses on colonial history.

Emily Cock, a lecturer of Early Modern History at Cardiff University said, “To consider Britain in isolation from the rest of the word, and especially without paying close attention to the regions where the English and then British people invaded and/or had frequent interactions is simply to get half the story. People, things, ideas and money flowed both ways in the Empire, in ways that historians have increasingly demonstrated and public institutions have begun to acknowledge as parts of their story.”

This also breeds ignorance within the British youth when ethnic minorities share their lived experience of discrimination in the country they are met with a culture of denialism. Teaching the empires legacy would go a long way in changing people’s perception of ethnic minorities in the country.

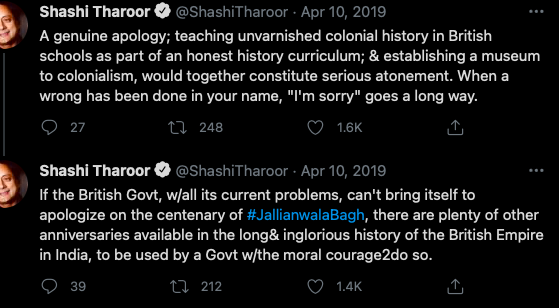

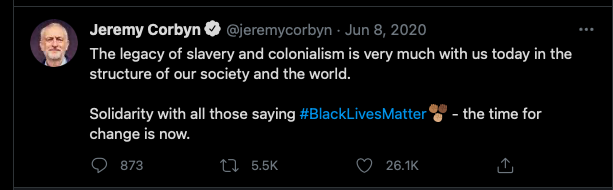

Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the Labour Party in 2019 vowed to teach colonial history in Britain promising to bridge the historical gap.

However, the proposal was met with criticism with Tom Loughton, Conservative MP arguing that putting colonisation in the textbooks would make history ‘political’ and that it would make children ashamed of their country., while Jacob Rees Mogg another conservative leader said that, “While there were blots on Britains’ colonial history there were some good bits which were wonderful.”

Politicians in the country have tried to not only rewrite history but also whitewash it with Boris Johnson in 2018 calling Britain the birthplace of democracy. He said, “a freedom-loving country, and if you look at the history of this country over the last 300 years, virtually every advance from free speech to democracy has come from this country.”

Such statements not only show ignorance about imperialism and history but also ignores the impact of empire on those colonised. It weighs down to railways vs the exploitation of millions of abolishing slavery vs building concentration camps during the Boer war. Erasing the latter out of teaching erases years of symbolic violence the empire committed.

To highlight Britains role in abolishing slavery, shouldn’t it be necessary to acknowledge how it benefited out it too and the role it played? When talking about the ‘good bits’ of the empire, which side of ‘good bits’ are we looking at?

Germany has demonstrated that inculcating the dark side of a countries past promotes a healthy conversation and doesn’t let history repeat itself.

Being able to interrogate, question and navigate the identity of the empire through conversations allows one to understand connections between people and the world and gives a better understanding of the present.

Tom said that “Studying history mainly benefits people by looking at the progress of compassion in humanity. So I would say that colonialism should be taught, and the overall effects of colonialism should be taught, such as cultures being diluted, to give students the awareness that something important has been lost as an effect on past human actions.”

Although the proponents of the Empire say it brought various economic developments to parts of the world it controlled, critics point to massacres, famines and the use of concentration camps by the British Empire.