Cancer patients could benefit from more targeted treatment due to discoveries made by Cardiff University researchers.

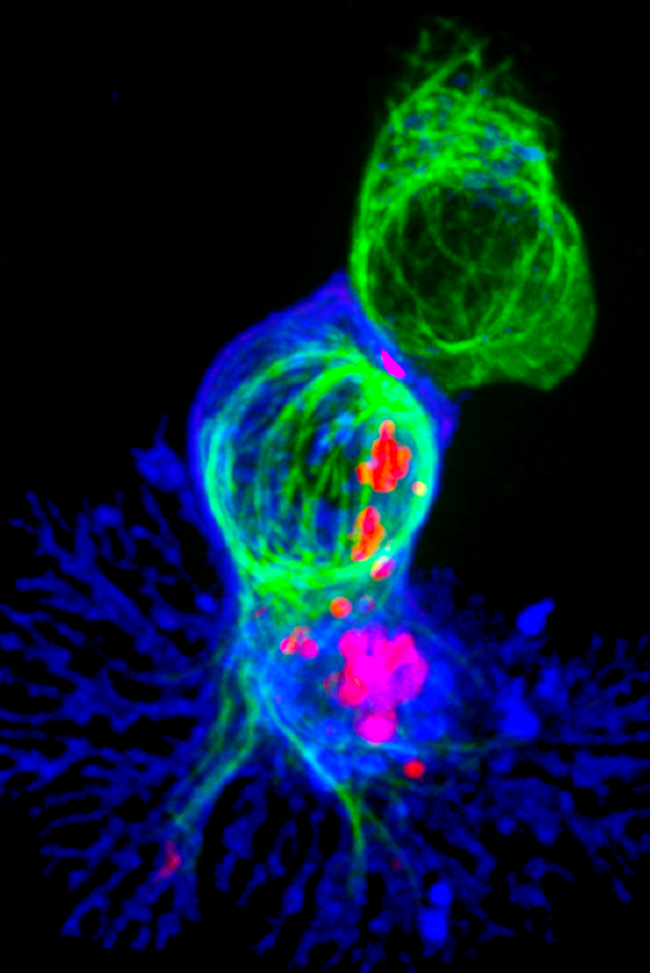

Cellular hit men: T-cells engaging a target. The red clusters are signalling molecules, indicating that the cell has found its target. Image credit: NIH Image Gallery. Images used are in the public domain.

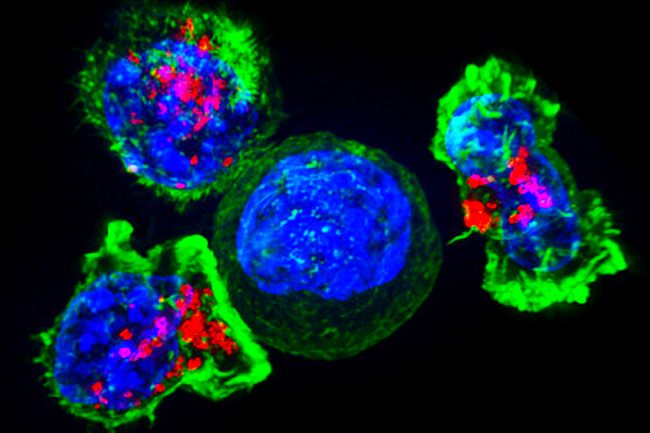

“The kiss of death”: Clusters of killer T-cells (green and red) target a cancer cell (centre). The T-cells attach and spread over the cancer cell, releasing chemicals through vesicles (red). Once the cancer cell is destroyed, the T-cells move on to another target. Image credit: NIH Image Gallery. Images used are in the public domain.

Cancer patients in the UK could benefit from treatment which enables their own immune system to find and destroy cancer cells, thanks to research from Cardiff University.

The research showed that the immune system’s white blood cells, called T-cells, are better able to locate cancerous cells when they are given a specific receptor.

“Cancer is good at hiding from the immune system because tumours have a disorganised arrangement of blood vessels, so therapy doesn’t reach the cancer through the bloodstream”, says Professor Ann Ager of Cardiff University.

Whilst this can be combatted with drugs which restore the blood vessels to a normal state, the immune cells have not yet been able to locate tumours in different areas of the body.

The key discovery made by the team was of a protein called a TCR or T-cell receptor which enables the immune system to find a wider range of cancers.

“The T-cell receptors discovered recently can differentiate between the protein on a healthy cell and one on a cancerous cell,” Professor Ager says.

“Here in Cardiff, we are working on improving the ability of T-cells to locate cancerous cells.”

The research has given hope to those who have rare cancers with limited treatment options, such as Mavis Nye. Diagnosed in 2009 with pleural mesothelioma, she was originally given just three months to live.

Nearly eleven years on, Mavis is a spokesperson for those with asbestos cancer and has helped countless people access clinical trials.

“This new research is amazing,” Mavis says. “I’m following the researchers and praying they do carry on. We are just around the corner from finding the answers.”

The immunotherapy drug which Mavis credits her survival to, Keytruda, works by stopping the cancer cells from being able to switch off T-cells by blocking a specific receptor.

However, Keytruda can cause unpleasant symptoms because it sometimes causes the T-cells to target healthy cells, which is why the new discovery of a receptor which can help the immune cells differentiate between healthy and cancerous cells is so important.

Clinical trials already exist for immunotherapy treatments like Keytruda which prevent cancer cells from ‘switching off’ the immune system, but research is also being conducted into the use of vaccinations in combination with these therapies for diseases such as late-stage colorectal cancer.

“Attempts at producing vaccinations for cancers not caused by viruses have largely failed,” Professor Ager explains. “Vaccines usually work when an infection isn’t already present.”

However, when used alongside immune-boosting therapies, it may be possible to create personalised vaccines using proteins on cancer cells called antigens. The immune system should then be able to recognise the antigens and kill the cancer cells.

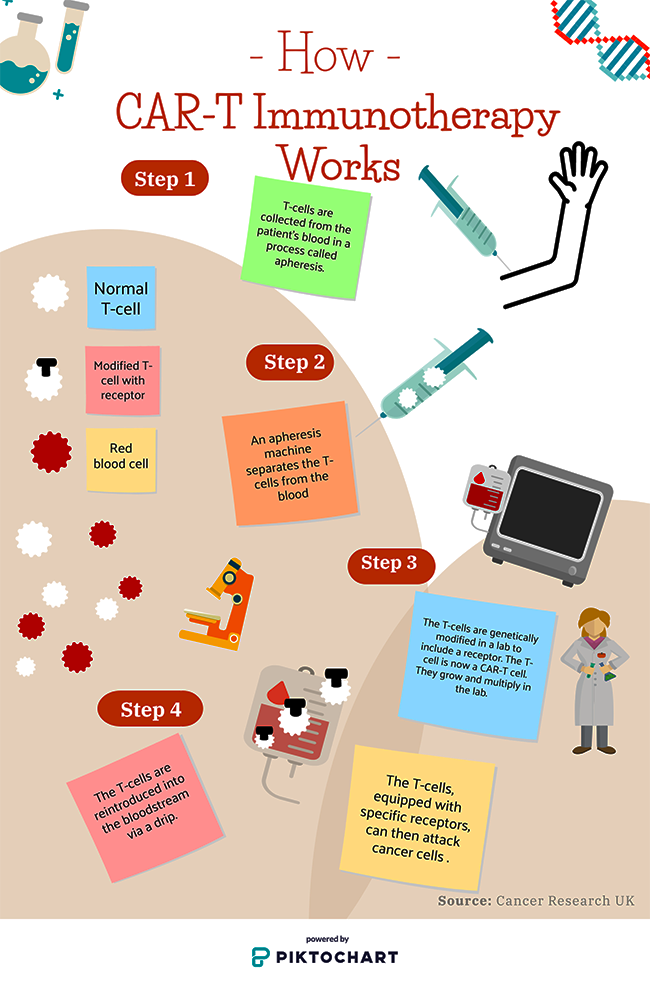

Current immunotherapies such as CAR-T therapy are being used in the University Hospital of Wales in Cardiff for certain types of leukaemia such as relapsed or refractory diffuse large B cell leukaemia (DLBCL), the most common form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

This therapy has been proven effective the US for blood cancers in children. Some patients in the US have even entered remission, which Professor Ager describes as a “wow moment” for researchers.

Existing CAR-T therapies can’t be used to treat solid tumours in different areas of the body, but it is hoped that advances in T-cell locating made by Cardiff researchers could mean that it will be able to target other cancers in the future.

Cardiff’s immunotherapy research is at an early stage and, importantly, has yet to go through clinical trials.

It’s a “slow process from the lab”, says Cardiff researcher Professor Awen Gallimore, but the process is getting faster as advances in research are made globally.

There are hopes that immunotherapies will soon be developed and administered to patients in Cardiff, which Professor Gallimore says may improve survival rates.

Various hurdles need to be overcome before these treatments are as much a staple in the fight against cancer as chemotherapy, such as the difficulty in predicting which patients will respond to treatment and the weakening of the immune system with age.

However, is still clear that this research has incredible potential, and the “explosion of interest” in immunotherapy that Professor Ager describes has drawn increased funding for further work. The scientific process is always continuing, and every development brings us closer to universal treatments.