A recent riot in Cardiff city centre before a football match has raised worries about the return of football violence. But why do experts say it is an anomaly?

As dusk fell over Cardiff city centre, tensions flared near the train station, where the police were deployed to manage a large crowd. Clashes erupted between two rival groups, waving football flags, as emotions ran high. Officers on horseback worked to separate them while some individuals threw objects.

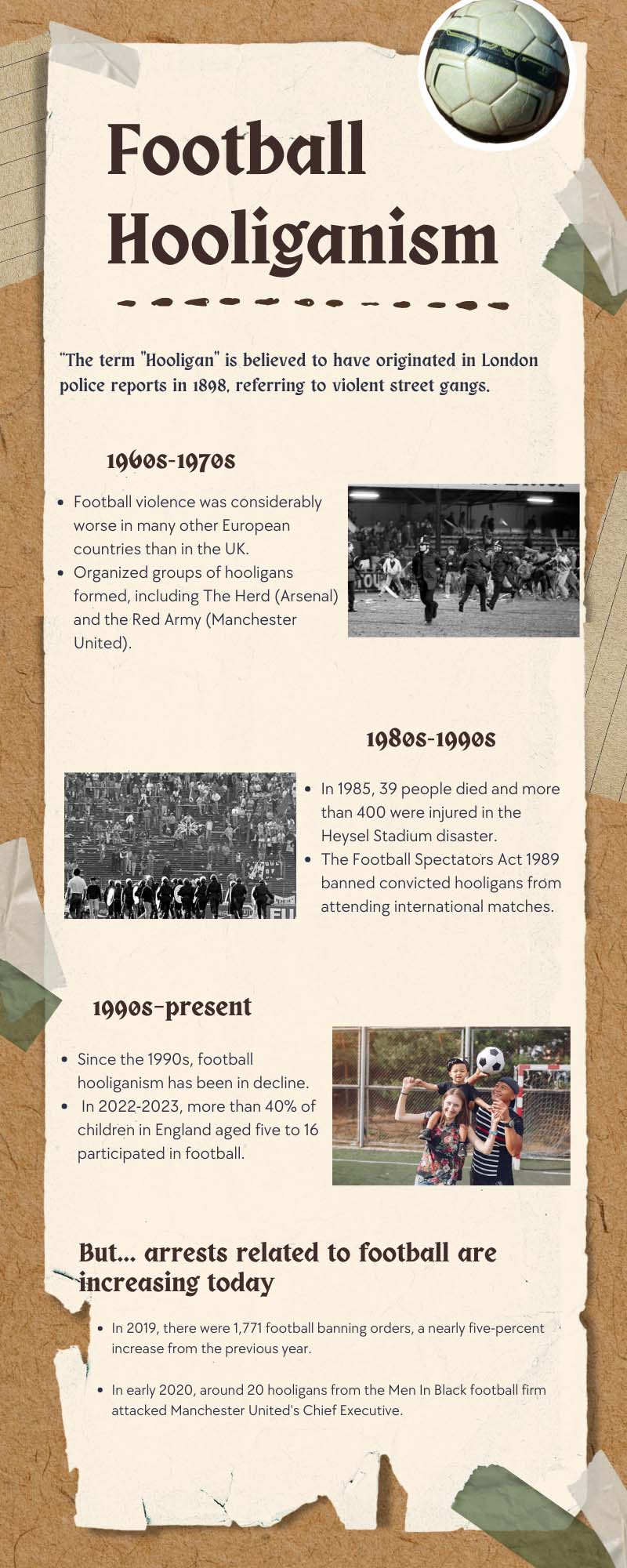

Footage of the incident circulated on social media two weeks ago, described as a riot involving Cardiff City and Bristol City fans. Some online comments suggested that “hooligans” were back, and is football violence returning?

“There is very little violence today,” said Keith Morgan, Chair of the Cardiff City Football Trust. “The media built that up. All it was people took Bristol City fans the wrong way through the city centre, and about ten of them started throwing things at the public. There was no violence between fans.”

Keith has been a football fan for 62 years, attending his first Cardiff City match in 1962. Reflecting on the past, he acknowledges that football violence was once a severe national issue.

“It was a real problem, not just in football. It almost became part of the fashion and was tied to gangs. Derby games were dangerous then,” he said.

Since 1980s, football violence has significantly declined. In the late 1980s, football-related arrests exceeded 6,000 per season. By the 2022-2023 season, this number had dropped to 2,264.

“CCTV is everywhere. Once you start violence, the police will catch you quickly. Also, with social media, offenders can be identified easily,” Keith said.

Following the incident in Cardiff, a teenager from South Gloucestershire has been charged with a Section 4 Public Order offence and bailed, according to South Wales Police.

Recent Home Office statistics show that while overall football-related arrests increased from 2023 to 2024, the number of matches with reported incidents dropped by 12%. This suggests that while fewer matches experience disorder, the incidents that do occur may be more severe or lead to multiple arrests.

“The rising cost of tickets also contributes to the decline in violence. Higher prices select who can attend matches,” said Keith.

In the 1990s, as clubs modernized their stadiums following the Taylor Report—which recommended the removal of standing terraces—ticket prices rose sharply. This shift priced out those more likely to engage in hooliganism. Arsenal’s move from Highbury to the Emirates Stadium in 2006 saw ticket prices increase dramatically, attracting a more family-oriented audience.

Two weeks after the Cardiff unrest, the Football Association charged Bristol City with failing to prevent offensive language from spectators during a match in October last year. The club is accused of not ensuring that supporters conducted themselves in an orderly manner.

To promote a more positive football environment, supporters’ clubs are taking steps.

Jane Ford, a representative of the Cardiff City Supporters’ Club, also said that football violence is very minimal today and the chaos two weeks ago was an independent supporters that arranged.

She emphasized the increasing presence of families at matches. “People come with their children, buying merchandise and programs. Football is more of a family event now. I feel completely comfortable bringing my children. Even as a woman, I feel safe. We have a lot of female supporters who travel with us.”

According to FIFA, the 2022 World Cup saw a record rise in youth engagement, with over 5 billion people tuning in, many watching with their families. The English Premier League reported a 30% increase in junior season ticket holders over the past decade. Clubs are investing in family-friendly initiatives, such as dedicated zones, discounted tickets for children, and interactive matchday experiences.

Beyond attendance, digital engagement among young fans is growing rapidly. A 2023 UEFA report found that 70% of Gen Z football fans follow their favorite teams on social media. Clubs like FC Barcelona and Manchester United boast millions of young followers on platforms like TikTok.

This shift shows that football is no longer dominated by hardcore adult fans—it has become a shared family experience that continues to evolve.

“In the 1980s, violence was a real problem throughout football. I still remember how disappointed I was when I witnessed an incident for the first time,” Keith said. “But people grow up. It is controlled now.”