Two years ago, she had never run a day in her life. But for Wales’ Kerrie Aldridge, running isn’t about finishing times. It’s about finishing lines, showing that every runner counts and most importantly, her son waiting at the end of them.

It was somewhere near mile 15, the clock barely ticking over five hours, that Kerrie Aldridge’s five-year-old son Osian told her she should’ve run faster.

“I know, I know. I’m so sorry,” the 40-year-old Cardiff mum recalls saying in tears. She’d just reached Canary Wharf, slightly over halfway through the 2019 London Marathon.

What was an intended milestone of a year-and-a-half long journey from never running a day in her life to moving her “short arse legs” the elusive 26.2 miles had begun to feel more and more like a terrible nightmare. No crowds, no tracking mats, half-drunk water bottles strewn on the ground to quench her thirst.

So Osian Aldridge did what good 5-year-olds do: He smiled and wrapped his mum into a hug. “Don’t worry, Mummy,” he said. “Momo’s (Mo Fara) had a bad day too. He didn’t win either.”

So Kerrie cracked a smile and continued the next 12 miles, ignoring the fact the Marathon had already stopped recording her time and the crews were washing away her path as soon as her feet hit the pavement.

If you told Kerrie Aldridge as she danced with her blue-dyed pixie cut at last year’s London Marathon start line that she’d become a viral inspiration from placing absolutely dead last before she’d even finished, she would’ve told you to shut up.

In fact, she already did this.

“My best friend saw me and said it,” says Kerrie, a.k.a. Instagram’s Crazy Kezza, a self-described “little short-ass, plus-sized mummy with little legs” running on her campaign ‘Every Runner Counts’ in hopes to spread the message to empower a new generation of runners after last year’s fiasco.

But on the day, Kerrie had a different focus: She was busy running to Osian. So instead she said: “Shut up, what are you talking about? I’m trying to run here!’”

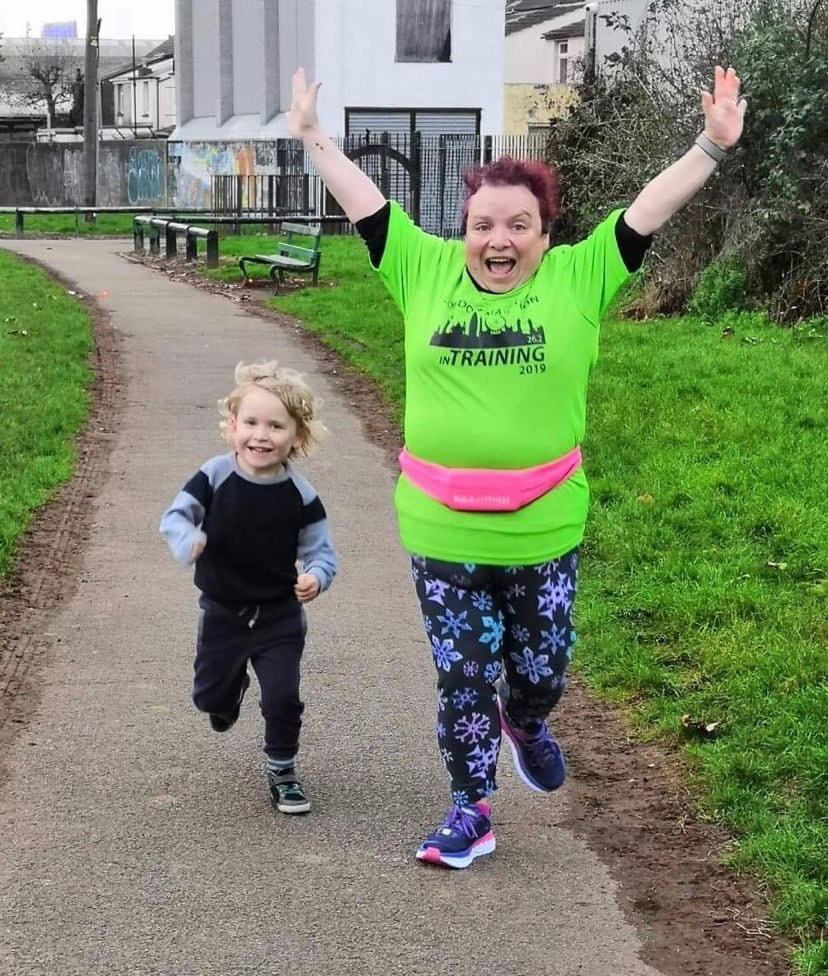

Less than a year and a half before London, Kerrie’s influencer future was less than auspicious. She’d never run a day in her life, loathed taking pictures of herself. But her blonde-haired little boy had turned four-years-old, she was nearing 40, and she could barely run in the park with him. She simply wanted to be a better mum.

“I remember growing up as a kid and being bullied. I didn’t want that for [Osian],” she says. “I always tell him when you reach for the stars, you can do whatever you want. It’s so important from an early age that I show him that.”

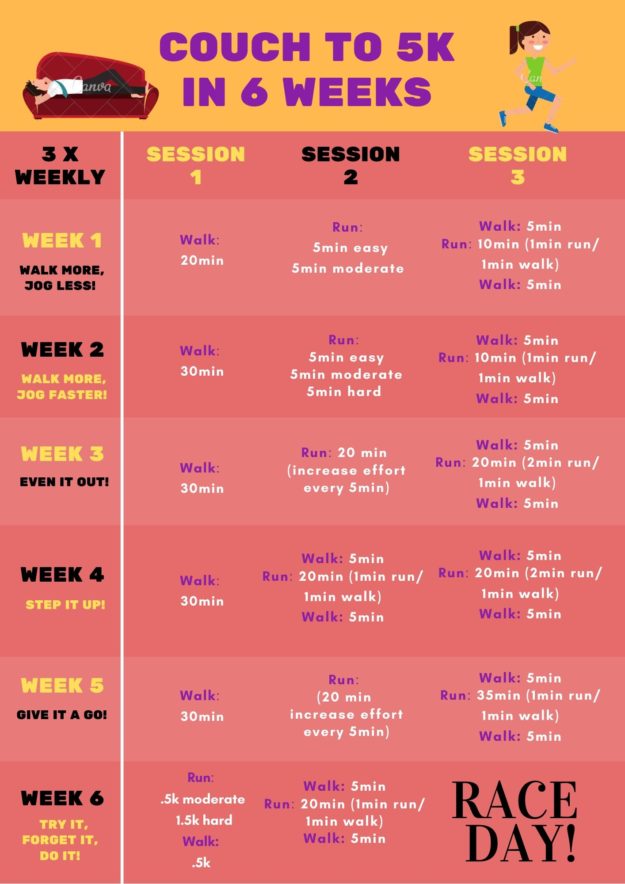

Since January 2018, Kerrie hasn’t stopped. Not when she could barely run more than 60 seconds consecutively at her first plus-size running session. Not when she was in such pain at Tesco afterwards, she pushed a trolley around the lot until the feeling returned.

“I thought, ‘What the hell have I done? I’m never ever going to be able to do this,’” she says.

Kerrie did stop for a moment when cajoled into dancing with a besotted crowd at last year’s Cardiff Half less than a quarter mile from finishing – but then she kept going.

“My trainer was yelling at me: ‘Kerrie, you’re a serious runner now!’ But I’m a bit terrible.” She smiles bashfully. “I hear the music and just start going with the crowd.”

But perhaps most astoundingly, Kerrie still didn’t stop when the London Marathon clean-up crew was pulling down the entire marathon’s gantry from around her as if she’d missed curtain call.

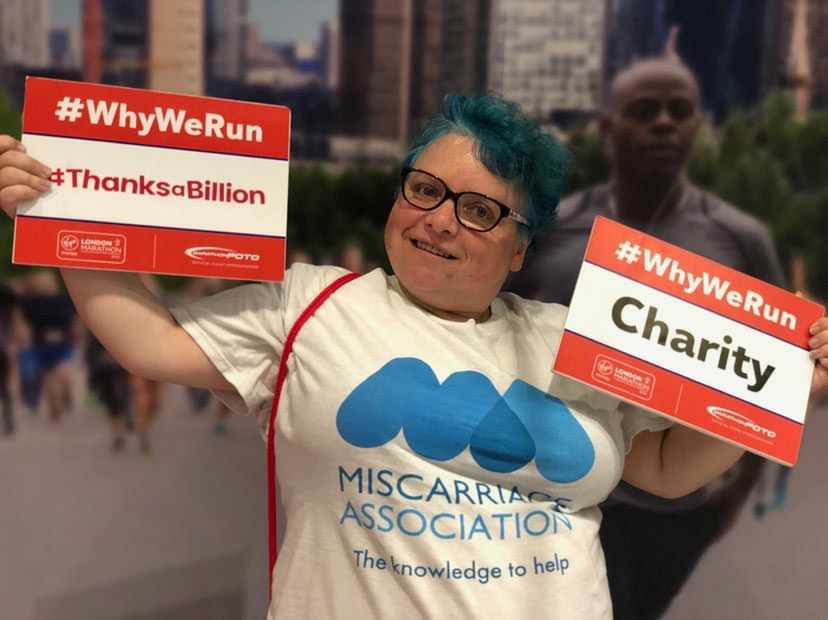

Sporting her Miscarriage Association vest, Kerrie had to keep running: for Osian, for her own five “angel babies” and the £5,000 she’d raised dedicated to each one of them and for all those who shared their own stories of loss with the mum who never before considered sharing her story. Kerrie had to keep running. Everything else was background noise.

But when her Garmin lit up as she neared London Bridge asking why she’d stopped at 10k, Kerrie was understandably peeved:

“What do you mean? I haven’t stopped running!”

She easily could have. Reaching the finish line at 9 hours and 11 minutes, the Marathon’s official last place racer, Kerrie was one of 200 back-of-the-packers who ran quite different marathons from those touting PBs and finishing to whooping bedlam.

Three miles in, clean-up crews were well on their tails. Tracking mats and mile markers snatched before they’d reached them. Photographers vanished home. When water stations disappeared, Kerrie drank from half-drunk bottles dumped by earlier runners.

Even the blue line signposting the shortest route for hitting the 26.2 miles under the seven-and-a-half-hour cut-off was removed by chemicals almost as soon as runners’ shoes left it.

“[The crew] were saying things like, ‘You’re too fat to run. If you lost weight you’d run faster. You shouldn’t be running a marathon. It’s a run, not a walk,’” Kerrie recalls.

The London Marathon has introduced new inclusivity measures for this year’s race after Kerrie and other runner’s testimonies:

Yet, Kerrie kept running, and nearing London Bridge, took to Facebook to let friends and family know she was safe. But as she turned the corner, she began crying.

“Everyone says the bridge is the defining moment of the London Marathon. They talk about a wall of sound from all the supporters,” she says.

“I turned the corner and there was no one there.

“So I was putting this video on and I said, though tears, ‘They’re packing up all around me, but I don’t care. I’m going to finish. I said I’ll do it.’ I had to.”

By mile 13, Kerrie had gone viral — and the response was immediately emphatic.

“It really is crazy,” she says with a laugh. “I still have people tell me I’ve encouraged them to run, to share their story.” She shakes her head, her smile nearly folding into itself as if trying to hide.

“But I’m me, me with my short arse legs. I just did my thing.”

Her ‘thing’ raised more than £12,000 for the Miscarriage Assocation in that race alone. Messages from as far as Israel begged her to keep sharing her story, to keep running for her babies. On a vacant street near mile 17 of the London Marathon, a woman rushed to hug Kerrie after spotting her Miscarriage Association vest. Today, Kerrie has half her miles dedicated already for her return to London in October.

“One of my friends said to me recently, ‘If you weren’t such a shit runner, you never would’ve raised so much money and awareness for your charity,’” Kerrie says. “Other people were really cross with her, but in a way, it’s true.”

“If I was a normal runner, all this stuff wouldn’t happen.”

The thought of Kerry being a ‘normal runner’ seems (for wont of a word) crazy. As she says, it was always meant to be hard. But every good crazy idea is.

“When you have a crazy idea, you really apply yourself to it, really focus,” says Kerrie. “When it’s the good crazy, you have a goal you want to achieve it and you can.”

Early on, Kerrie toed start lines fidgeting before cameras. She hated running in public. Even as she reached 10k two months after starting and began running where people could see her, her thoughts wandered:

“They’ll be fed up waiting. They’ll think, ‘Why the hell is she running? Look how slow she is,'” she says. “But we’re our own worst enemies.”

To Kerrie, running has become viscerally anything more than running. It’s a 7-mile “chicken soup for the soul in crazy times” she never thought she’d taste, a community she worried wouldn’t accept her but instead found embraced her.

It’s standing at four-feet-seven-inches and boasting brightly-patterned spandex mid-stride in Instagram posts, adding extra minutes to finishing times to caper with the crowds. It’s panic-buying kettle balls instead of eggs or chocolate in the midst of a crisis and still sharing inspirational quotes and daily Stravas so those who follow her know, crazily enough, she hasn’t stopped running and neither should they.

“Running is for everyone. It’s amazing,” she says. “We should celebrate every runner and every run.”

So as the London Marathon approaches in October, Kerrie doesn’t fear it. As hard and crazy as it seems, she thinks of the good.

“And so much good has come from it,” she says.

While she’ll strive for a 7:46 hour time and train every day until it comes, time is relevant.

“I’m at that stage where I’m not doing this for anyone else. I’m doing it for me and Osian,” she says. “Someone’s gotta come last. He’s going to grow up, go through different things he won’t be very good at. If I show him it doesn’t matter going last, then hopefully it’ll help him.”

At mile 26, Kerrie technically finished last. She didn’t cross any official line, rather a stand-in erected to the side. Chinese tourists walked up the park’s path as she ran through. She shouted. They parted and stood on opposite sides clapping.

But as she strode through, she didn’t care she wasn’t greeted by the crowds she was promised. At the end was Osian.

“He threw his arms around me and said, ‘Mummy, I love you just the way you are,”” she says. “And for me, they could keep the medal. They could keep all of that.”