A recent case in Wales reignites fears that many still overlook coercive control as a crime. Could this be a turning point?

At first, it felt like love. He messaged her constantly, wanted to know where she was, and said he just cared. Then he took her bank card. Controlled who she could see. Tracked her movements. By the time she realized it was abuse, she had no way out.

“Many survivors don’t recognize coercive control at first,” says Yashiba Sanil, Communications and Campaigns Officer at Welsh Women’s Aid. “It often disguises itself as care before escalating into total control.”

Coercive control doesn’t leave bruises. It’s an invisible crime, one that strips victims of their freedom, finances, and sense of self. And in many cases, it goes unnoticed.

In 2015, the UK criminalized coercive control, recognizing it as a pattern of psychological, financial, and emotional abuse. But nearly a decade later, many victims still don’t realize it’s happening to them.

Mathew Taylor, a senior official at the Welsh Government’s Social Justice Department says that Coercive control is an invisible form of abuse. “People think of domestic abuse as physical violence, but coercion is just as damaging.”

Despite rising awareness, reports of coercive control remain low. Many victims dismiss the early signs as acts of love or care, unaware that they are being manipulated into complete dependency.

Yashiba Sanil from Welsh Women’s Aid said that for every case reported, many more go unheard. “Many survivors don’t come forward because they fear they won’t be believed or don’t recognize it as abuse.”

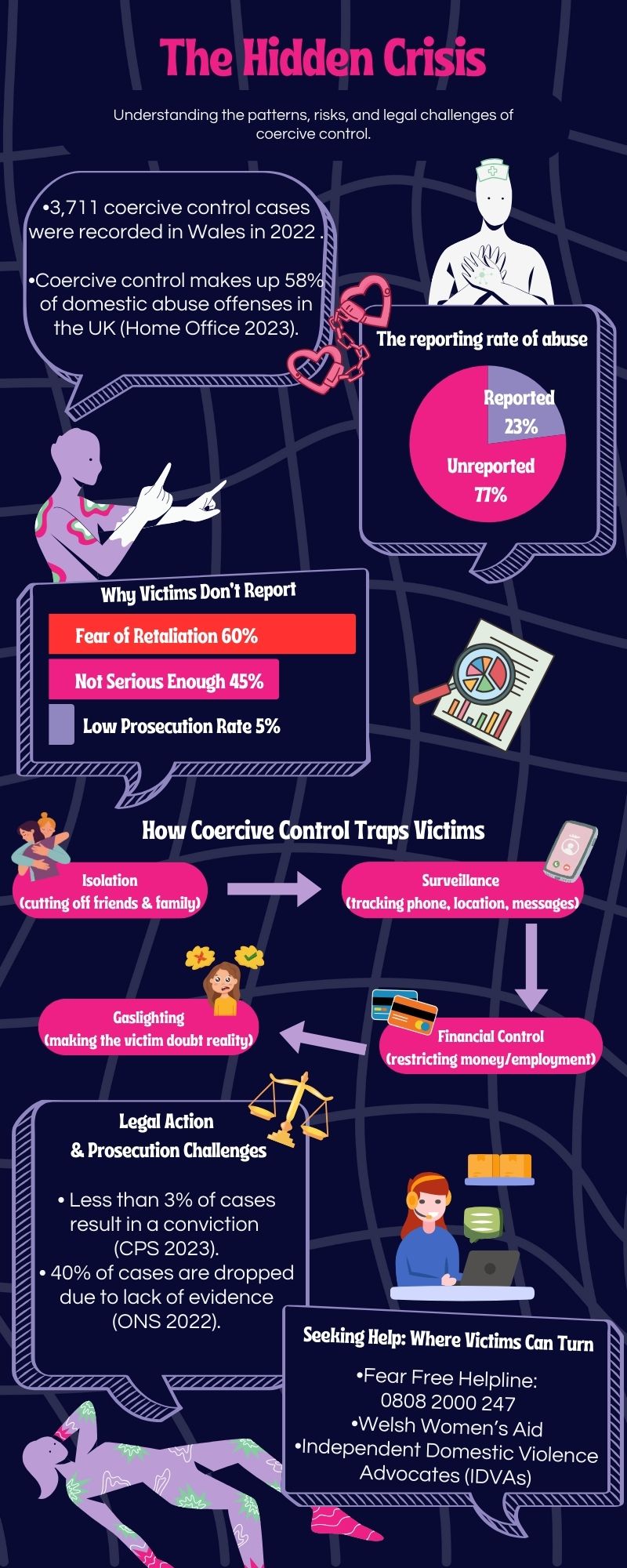

In 2022, Welsh police recorded 3,711 cases of coercive control, but domestic abuse charities estimate the real number is significantly higher. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported that 77% of coercive control victims in the UK never go to the police. Many fear they won’t be believed, while others remain unaware that what they are experiencing is a crime.

Recent cases in Wales have reignited debate on coercive control. Taylor stresses the need for stronger legal protections to ensure survivors receive justice.

Although the Welsh Government has not formally adjusted its policies in response, officials acknowledge that cases like this fuel the need for change.

“This case highlights why awareness is so important,” Taylor says. Lack of awareness is one of the biggest obstacles to justice. As Taylor says: “If victims don’t recognize coercive control, they can’t report it. And if they don’t report it, they can’t get help.”

Coercive control is already illegal, but Taylor says that legislation alone isn’t enough. Without public education, early intervention, and better enforcement, many victims will never escape.

Victims struggle to provide clear evidence, police find it difficult to prove patterns of abuse, and cases without physical violence are harder to prosecute.

“One of the biggest barriers to justice is that coercive control cases often rely on psychological evidence,” says Sanil. “Unlike physical abuse, it’s harder to prove in court. Many survivors struggle to collect the necessary evidence while still being manipulated by their abuser.”

Many coercive control cases end in bail conditions or no further action due to a lack of evidence. However, recent high-profile convictions have given some hope that perpetrators can and will be held accountable.

“If victims come forward, action will be taken,” says Taylor. But many still don’t believe that’s true.

Escaping coercive control isn’t as simple as walking away. Victims often face financial dependence, making it impossible to leave, psychological manipulation, making them doubt their own experiences, and fear of retaliation, discouraging them from speaking out.

Many who do leave suffer from PTSD, anxiety, and isolation, forced to rebuild their lives from nothing.

Recognizing coercive control before it escalates is crucial.

The Welsh Government’s Sound Campaign targets men aged 18-35, encouraging them to self-reflect on controlling behaviors. It asks questions like whether they are messaging their partner too much, feeling the need to check their whereabouts, or controlling their friendships.

Educating people before coercive control starts could prevent abuse before it happens.

Wales has a comprehensive support network, including Live Fear Free, a national helpline offering confidential advice, Welsh Women’s Aid, providing tailored support for survivors, and Independent Domestic Violence Advocates (IDVAs), who offer case management.

“We fund services across all five regions,” Taylor says. “97% of our budget goes directly to supporting victims.”

But is it enough? Sanil says more funding, better police training, and wider awareness campaigns are needed.

Welsh Women’s Aid highlights that certain communities face unique barriers. “For migrant and minority women, coercive control can be even harder to escape,” says Sanil. “They may not have access to public funds, and cultural stigma can prevent them from speaking out.”

Taylor believes the following key changes are necessary. More training is needed for police to recognize coercive control. Stronger protections must be put in place to make prosecution easier. Better education in schools and workplaces can help prevent abuse before it starts.

“We also need communities to play a role,” Sanil said. “Survivors may not always go to the police first. They might confide in a friend, a doctor, or even a shopkeeper. If communities recognize the signs, they can help direct victims to support services.”

“We need to listen to survivors,” Taylor says. “Their experiences should shape future policy.”

Coercive control remains largely invisible, yet its effects are devastating. Without recognition, victims will continue suffering in silence.

“If you’re experiencing coercive control, you’re not alone,” says Sanil. “Help is available. Even if you’re unsure, reaching out is the first step.”