EVERYONE has a different idea of what makes a normal Christmas Day. For some, it’s the first sip of buck’s fizz at a totally unacceptable time of day.

For others, it’s bowls of pigs in blankets and rubbish Christmas cracker jokes. Midnight mass, the Gavin and Stacey Christmas special, or endless board games fuelled by post-dinner Baileys. Everyone has their own ideal Christmas.

What makes all these things enjoyable, though we might not admit it, is being with friends and family. Even miserable golf-obsessed Uncle Ken. No-one wants to be alone.

This year, the UK became the first country in the world to appoint a minister for Loneliness.

Tracey Couch took up the role, created in the wake of the Jo Cox Commission on Loneliness. The commission was set up as a legacy for the Labour MP, who was murdered by a far-right extremist in 2016.

In 2016, Age UK carried out a nationwide survey and discovered half a million older people go five or six days a week without seeing or speaking to anyone. This year, the British Red Cross surveyed 4,000 people of all ages, a third of those said they often felt alone. A fifth said they had no close friends.

It’s at Christmas, when most of us are catching up with friends and family, that those suffering can feel most alone.

For a lot of people who feel lonely, it’s not that they are alone physically, but they have a disease or a disability which makes communication difficult to the point where they can feel alone even when sitting at the dinner table on Christmas day with the people they love.

This feeling of being “alone in a crowd” is something most of us have probably experienced at some point.

Martin Griffiths, works for a pan-Wales service, Live Well with Hearing Loss. The project is aims to improve the lives of those with hearing difficulties. Martin himself is partially deaf and knows how isolating and stressful the Christmas period can be.

“Every year we get deaf and hard of hearing people telling us about problems they have with their families. There might be games and singing and catching up, but often people who are hard of hearing feel like they are struggling through. They make the decision to isolate themselves. They feel a little angry and a little sad that they are with people they love but cannot join in as they used to.”

This is most distressing for those who have recently lost their hearing. It can take up to 10 years for people to fully come to terms with the fact that they are going deaf.

Over that time, they often detach themselves from those around them, and do not seek the help and support that they need.

This reluctance, is partly due to attitudes and prejudices towards those with hearing problems. Martin gave an example of a deaf man and his partner who go shopping. The deaf person asks a question in a store and the shop assistant addresses the reply to his partner. It is easy to see how constantly experiencing moments like this can leave you feeling segregated and alone.

There are plenty of simple ways to make people feel more included.

“That might be turning the TV down in the background, playing games which are less reliant on hearing. Or using basic communication like looking straight at people and speaking clearly.”

The number of deaf people in the UK is growing each year, primarily because people are living longer. Longer life comes at a cost, and it has also led to a rise in the number of people living with dementia.

There are 850,000 people with dementia in the UK, with that number set to rise to over one million by 2025.

About 225,000 will develop dementia this year, that’s one every three minutes.

Loneliness is just one of the many issues that people living with dementia have to contend with.

Rhiannon Donnelly, is a co-ordinator for Side by Side, a project run by Alzheimer’s UK: “We face a real problem over the coming years as the number of people with dementia grows, healthcare services will come under increasing pressure.”

“We begun this scheme to help those living with dementia by providing company and support on a weekly basis.”

Serena Purslow, is an experienced volunteer for Side by Side:

“Side by Side work to try and find you a person with the same sort of likes and interests and it goes from there really,” she said

Serena has been working with the charity for the last four years. She has been going to visit her current service user, who has early onset dementia and is only in her 50s, since February.

“She’s lovely and she’s grown so much in confidence. When I first went there, she wouldn’t open the door so I would stand on the doorstep and chat with her through the door.”

“Now she looks forward to our day, we go shopping, go to the park. We tend to do the things she liked to do before she had Alzheimer’s. But if she’s having an off day and won’t eat, I know if I give her dessert first, she’ll eat her lunch. She makes me laugh.”

“She’s very witty, she tells me off if I’m walking too fast. She’s more like a friend than someone I go and help for a couple of hours.”

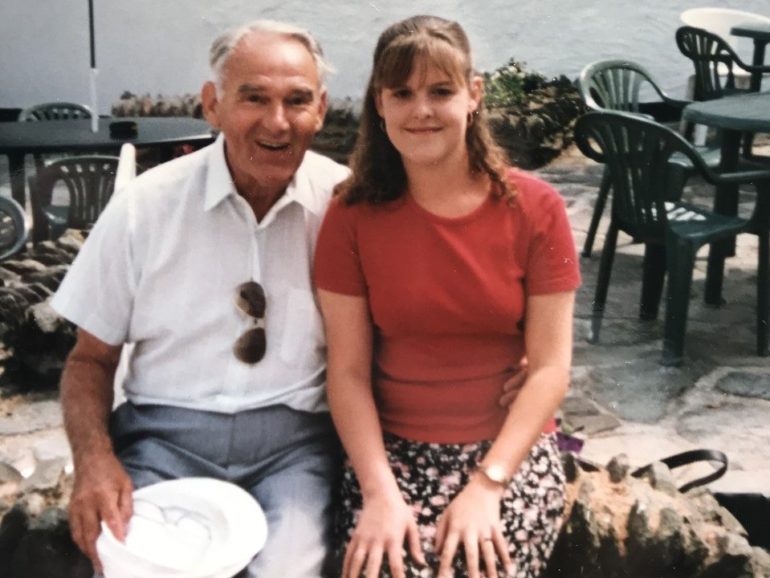

Serena got involved with the charity as a result of her own experiences with Alzheimer’s. “My Grandad had Alzheimer’s and because my Grandma is very old school, at first, she didn’t want to ask anyone for help. I’m quite different in that respect.”

Christmas can be especially difficult for those with Alzheimer’s. Losing the ability to talk coherently and keep up with conversation means those with the condition can feel isolated and anxious.

“It can be a difficult time. The lady I am seeing at the moment stresses about it because she doesn’t like being with lots of people when she can’t communicate. Her parents came up at the weekend and she got quite worried about that.”

Serena is passionate about her volunteer work and wants to try and spend more time with her service user in the future.

“The hardest thing is going home at the end of the day. She’ll ask me: ‘What are you doing today? Why don’t you stay here, I have a spare bedroom? You can stay here and we’ll have a party.”

Side by Side and Live Well with Hearing Loss provide many other benefits to the people they support and there are dementia cafés and deaf-friendly groups that people can join.

However, Serena and Martin both believe that sometimes, these places can make people feel worse about their condition.

“It reminds them of what they can’t do. My lady would prefer to be out and about rather than be with other people with dementia because she would have to confront her illness again.”

The best way to help is the easiest; treat people as you would normally, be patient and imagine if it was you.

Serena Purslow (left) with her Grandad (right)