As reigning world champions, WRU Deaf look ahead to their first international match post-Covid and the world cup next year

WHEN I made plans to attend a Wales Deaf Rugby training match, I was prepared to learn about an entirely new sport.

In my mind, players wouldn’t be tackling as hard to avoid damage to hearing aids, referees would have to wave flags instead of blowing a whistle, and the game would be quiet as players couldn’t shout to communicate.

But that couldn’t be further from the truth.

For one, WRU Deaf played against Cardiff Met Archers, a hearing team. While they do take on other deaf teams in international matches and the World Cup, I didn’t expect them to compete against hearing teams.

As I watched the Welsh Rugby Union’s deaf team give their all in the second training match post-Covid, it was easy to forget that every player had some form of hearing loss.

The referee still used a whistle, players and coaches yelled to each other on the pitch, and the tackles were just as hard, with a high skill level on display.

So, what is deaf rugby, and why is it separate to standard rugby?

In terms of rules and play, there is little to no difference in comparison with standard rugby.

Because the team ranges from those with partial hearing loss to complete deafness, the main difference is the consideration given to players who can’t hear the referee.

This can range from leeway in the rules if players don’t stop when the whistle is blown to having an interpreter on the sidelines in case the referee needs to explain a call.

“What you sometimes get is a slight difference in interpretation from the referee, where they might give you a little bit of extra time, 20 or 30 seconds, for players to discuss calls,” said RJ Coles, head coach for the men’s team.

“For those that are profoundly deaf and need signing, there’s an opportunity to get them in.”

Hearing aids are not allowed during games to avoid damage during tackles and contact, even though they are used in training. As a result, players who can’t hear anything without an aid use their eyes more than ears.

Ben Landers, 25, from Aberdeen said: “You make do with what you’ve got around you.

“You’ve got to rely on the people inside and outside of you, building up those networks and that trust. It’s so important for us as a deaf team and team community.”

“The idea is to be able to bring a group of players together, but not necessarily take them away from playing mainstream rugby,” said coach Mr Coles.

“When we do bring them together, they are able to compete and use that as an opportunity to share that just because you might wear a hearing aid, there is actually deaf and hard of hearing rugby available.”

The impact on the deaf community

For players, WRU Deaf allows them to compete at an international level and play for their country, something which they hope will inspire the deaf community.

John Higginson, 35, from Bedford, didn’t even realise how deaf he was until he got involved with the team, when he received a hearing test with the team’s sponsors, Hearing Aid Solutions.

“I found out through work that I was deaf through one of those random tests, so I reached out to one of my mates who plays here anyway.

“After my hearing test here, they said, ‘Well, unfortunately you’re deaf. The good news is that you can play.’ It was the best of both worlds.”

Mr Higginson played club rugby before joining WRU Deaf and was surprised at how skilled the players are.

“People think it’s a big disability when it’s really not. In fact, some of these boys who play here are much better rugby players then you will play with at a club level, because their awareness is so much better.

“The lads are just so aware. I go back to my club, and I’m like, ‘Boys, listen, you’re not as good as these boys that I’m playing with, and these guys can’t hear a thing at all’.”

Steven Moran, 33, from Devon, originally played for England Deaf Rugby but wasn’t happy due to travel times and the team atmosphere. After applying for WRU Deaf (he was eligible as his father is Welsh), he found his “brothers”.

The sport gives him a chance to inspire others in the deaf community and show the world that deaf people can do anything.

“It’s nice because in the past, I haven’t seen many disabled or deaf in this sport, so I’m hoping deaf and disabled people get involved in sport and show people what we can do.

“Some people say, ‘Deaf people can’t do this’ or ‘You can’t do that,’ but we can do everything. We are like hearing people, apart from our hearing is broken.”

Players hope WRU Deaf will encourage the next generation that they can participate in sport, regardless of their deafness, and compete at a high standard.

Mr Higginson said: “We’ve had kids turn up training, and deaf children will stand there and realise, ‘I can play for my country.’ Hopefully, we can be role models for them.

“And It’s not just about hearing – these boys have far superior senses than ours. It’s just a massive opportunity for anyone that wants to play.”

Beyond scheduled matches and the Deaf Rugby World Cup, coaches are looking to expand the sport into new competitions, from getting rugby 7s into the Deaf Olympics to a deaf rugby Six Nations.

“If we can do that, then that’ll give us even more exposure and just promote what’s going on.”

The first international match, post-pandemic

WRU Deaf now look ahead to a series of home matches against Ghana in April.

After returning to training last month – for the first time since the pandemic began – the games will be an opportunity for both teams to prepare for the World Deaf 7s Rugby championship in Argentina next year.

For many players, the Ghana duel is more than just a game.

“With an international match coming soon, it’s very exciting because us boys have been waiting for games for the last two years,” said Rhys Perry, 19, a student at Cardiff Met from Pyle.

“It’s something now to look forward to and raise awareness for deaf rugby, and for clubs like Ghana – they’ve been brought into the limelight and on the news in Africa talking about it, and in general for deaf rugby and deaf sport, that’s massive.

“For teams like Ghana who are coming up in standard rugby and deaf rugby, it’s massive for them as well.”

While they are friendly matches, the results will show how the WRU Deaf 7s and 15s teams are performing after two years off from training.

“For some of these lads, it will be a test to see where we are at 7s level. We’re the current 7s champions, so they’ve got nothing to lose by coming over here and we’ve got everything to lose in my eyes, but I’m just competitive.

“It’ll be good for both teams, not just us. And I think it’d be good for England as well, as they’ll be watching on and seeing where we’re at.”

Next stop: the 2023 Deaf Rugby World Cup

Most importantly, the Ghana matches are the first step in Wales preparing for the Deaf Rugby World Cup in 2023.

Wales 15s and 7s were both crowned the World Deaf Rugby 7s champions in 2018, after beating England in Australia, and they have held the title since.

“We’ve started planning now with tournaments and training, but we’ve got a whole year to prepare, and with the way we’re set up with our sessions planned, I’m going into it with confidence,” said Mr Perry.

WRU Deaf only had 12 weeks to prepare for Australia in 2018; now, they have 12 months.

Some of the biggest challenges come from new players joining the team, as building a team atmosphere and knowing how each player prefers to communicate is essential for deaf rugby.

“Hopefully we are ready for Argentina, but it’s a lot of work to do because some players – I don’t know who they are, so I don’t know what they like,” said Mr Moran.

“We’ve got to challenge each other and get involved to do well in the World Cup.”

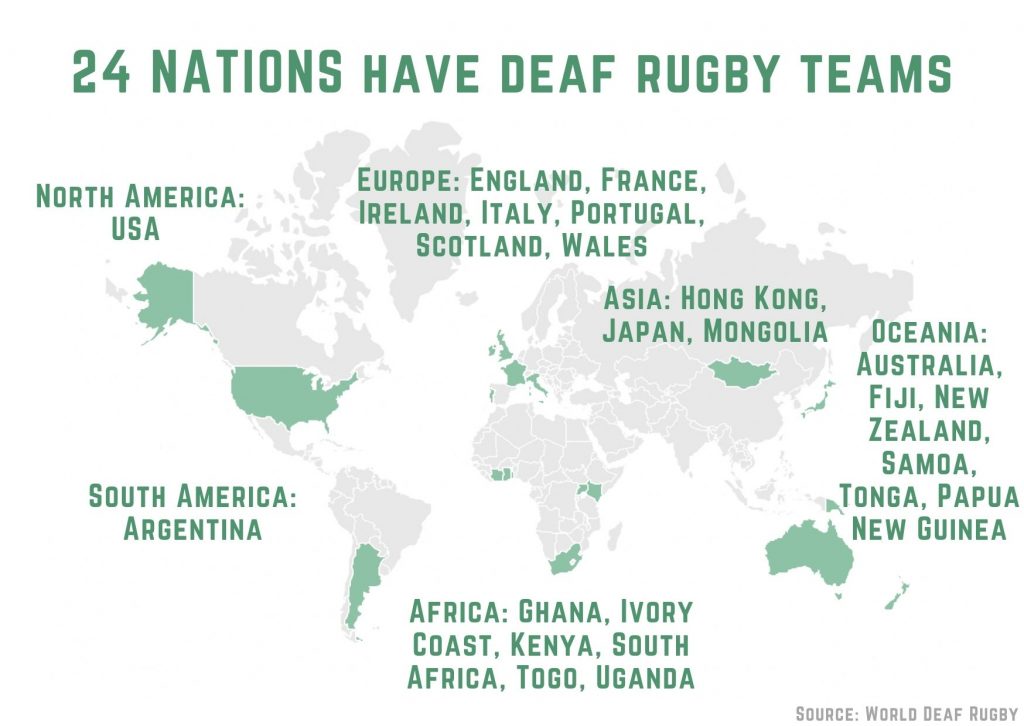

There were 11 teams who were ranked in the 2020 Men’s World Deaf 15s, but more, including Ghana, are expected to be involved with the 2023 World Cup.

While WRU Deaf are optimistic about the World Cup, the players all expressed gratitude that they have this opportunity in the first place due to being deaf or hard of hearing.

“It’s exciting. To be given an opportunity to go to the World Cup is crazy,” said Mr Landers.

“Without being partially hearing you’d never get these opportunities.”

- Those interested in getting involved with deaf rugby can visit their website here.

- WRU Deaf is also active on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, with the handle @walesdeafrugby.