Wales has the lowest levels of productivity out of any nation in the United Kingdom, bringing with it negative outcomes for living standards

A SHORTER working week could have a positive impact on the Welsh economy, climate change and the NHS, according to four day week campaigners.

From productivity troubles, to the need to lower our carbon footprint and improve outcomes for healthcare staff and patients alike; it is claimed that the four day week, short of being a silver bullet, could form part of the solution to the issues facing Wales.

The economic picture in Wales

Immediate challenges such as the £900 million shortfall in the UK Spring Budget, and the longer term battles like those against the highest poverty levels in the UK and ongoing/ incoming effects of climate change, make no secret of the many difficulties facing the Welsh economy.

However, few problems permeate Wales’ system of public finances quite like its long term struggles with low productivity.

For context, the nation currently ranks lowest in the UK in terms of GVA (Gross Value Added per hour worked), which measures labour productivity, and has done so for much of the previous two decades and beyond.

And there are numerous reasons for this struggle, according to Lydia Godden, an economic researcher at the Institute of Welsh Affairs (IWA).

“I think productivity comes down to a number of things,” she said.

“I think it comes down to a lot of people being economically inactive, and sort of physically not well.

“But then also, if you are well, but you’re less skilled and less educated, you’re not really able to get up to those higher paid, more productive roles, sadly.

What is ‘productivity’ and why does it matter?

The term ‘productivity’ can often sound like an abstract buzzword, bandied about by economists and politicians alike, and come to mean many different things.

But it is worth looking at the four day week debate with labour productivity in mind, i.e. output for each unit of labour inputted or, put simply, how much people’s work contributes to the economy.

And it matters because all productivity – whether it be labour or otherwise, on an individual business level or across entire sectors – ultimately contributes to a healthier economy.

Increasing it over time allows businesses to produce more goods and services which enables higher wages, economic growth and tax revenues – all of which helps grow our standards of living.

The Welsh Government’s Chief Economist Jonathan Price himself sees it as: “The key long run driver of sustainable increases in pay, prosperity and the tax base.”

“In the UK, productivity isn’t actually that high, but Wales is even lower.

“And we have so many people that are economically inactive, but that also comes down to long term sickness and illness.

“So we have a very impoverished, less skilled, sick society in Wales.”

One of the consequences of poor productivity in Wales has been the country adding less value to the wider UK economy than its home nation neighbours.

Gross Value Added (GVA) per head here, a key component in determining GDP (Gross Domestic Product) which measures economic growth, ranks lower than in Northern Ireland, Scotland and England, with Wales suffering from a poorer economy as a result.

And an economy that is not in a healthy state is, unsurprisingly, more likely to find itself struggling with issues such as:

- Lower wages, with businesses unable to produce enough goods to profit and grow from.

- Poorer public services, as lower tax revenues, fuelled by poor wages, reduces the government’s ability to spend.

- Unemployment, which is particularly relevant in the age of artificial intelligence if growth is too low to encourage firms to create jobs displaced by automation.

It is therefore no surprise then that these outcomes can lead to social issues, such as poverty which plagues Wales, particularly the ex-mining, deindustrialised areas, with almost one in four people nationwide finding themselves below the breadline.

So where does the four day week come into all of this? And could it be a solution to Wales’ productivity gap?

With Wales’ productivity issues well documented, and with the apparent benefits of the four day week for improving, or at the very least not reducing, the efficiency of workers well argued, it seems a natural next step to start talking about a shift in working patterns as one of, if not the solution to the Welsh economy’s struggles.

The IWA’s Lydia Godden is one of those who agrees with this view and believes that it is time for fresh ideas in tackling an issue that has plagued Wales for far too long.

“I think we’ve got to try different things now,” she said.

“Wales doesn’t look like the rest of the UK. Wales is very different in terms of our issues.

‘The status quo isn’t working’

“But we’re still trying to apply a UK level policy to Wales, when economically, Wales’ wealth makeup is completely different. So the status quo isn’t working.

“I think people are probably too set in their ways of how they understand the economy, how they understand, you know, a worker does a job.

“There’s input, there’s output. But I think we need to break away from that sort of understanding of productivity.

“And I think that’s where this idea could be really, really useful.

“I think we’d see interesting things. I mean, how many of us on a Friday afternoon think ‘that’s next week’s work’ and just sort of slow down a bit?

“We’re all too knackered by then to get anything useful done. And a lot of people clock off early anyway.

“So you either pay someone for a really rubbish half day, or you just pay them to go home and sort yourself out and do something else.”

As for that something else, Ms Godden suggests that there are things not including work that can also benefit the economy and the wider community.

“If you’re not working on that one day, you’re either going shopping and helping the economy and spending more money, or you’re probably either looking after yourself and your mental well being and taking time off the stress,” she said.

“Or you are, you know, helping your community out. I’d love to volunteer more, but there’s just no time in a week to do things like that.

“So I think there’s a lot of people that would like to give a bit of time to do other things. And if you’re paid that one day, you can do whatever you want.”

Research from the recent UK four day week trial appears to back this view up.

Prior to the trial, 87% of workers felt they did not have enough time outside of work to pursue other hobbies, this dropped to 54% by the end of it.

There was also a shift in the time people felt they had to volunteer, with 52% feeling they did not have enough time to do so by the end of the trial, down from 61% prior.

‘It’s not a silver bullet’

Despite the success of the four day week in many of its trials so far, it is still very much in its infancy as an idea in Wales (only two Welsh companies took part in 4 Day Week Global’s UK pilot in 2022).

And a common argument from those who see the merits of a shorter working week is that it is unlikely to be enough to solve Wales’ productivity struggles on its own.

This view is shared by Luke Fletcher MS, Plaid Cymru’s Economy spokesperson, who supports a four day week and was on the Senedd Petitions Committee which called for a government-led trial earlier this year.

“It’s not a silver bullet,” he said.

“I’ve often talked about a four day workweek being as part of a package with UBI, so universal basic income, or universal basic services.

“So I think we have to look at the four day work week as part of a package of policies.”

‘Some arguments used against the four day week were the same used against ending child labour’

The Senedd member for South Wales West also pushed back against some of the general criticism levelled at the idea, some of which has come from one of his colleagues on the committee, Conservative MS Joel James.

James believes private sector workers will end up ‘picking up the slack’ left behind by public sector workers who will likely be the proverbial guinea pigs in any potential pilot scheme.

“You know, for the work week it is a massive change in culture,” Fletcher said.

“And I think it’s important to recognize that and so you have to take people on a bit of a journey.

“But I would say that, you know, the sort of arguments around productivity that are being used against a four day work week, were the same arguments that were being used against the weekend and against ending child labour.

“And, you know, these are well rehearsed arguments.

“And arguments that we have evidence against, that shows that actually there is no negative effect on productivity.

“Again though, that’s why a trial is important, because we need to ensure that whichever sort of form of the four day workweek we’re using actually does deliver on positive productivity in the best possible way.”

Fighting climate change

Aside from productivity, there are also other pressing issues facing the Welsh economy, such as those related to the environment and the NHS, which could both see benefits from a four day week.

Natural Resources Wales predicts that climate change in Wales and the UK will bring with it more intense rainfall, flooding in low-lying coastal areas and hotter, drier summers, among other problems.

A 2021 report commissioned by four day week campaigners found that a shift to a shorter working week could shrink the UK’s carbon footprint by 127 million tonnes per year by 2025.

For context, the UK’s entire carbon emissions in 2022 were measured at 331.5 million tonnes with this potential reduction equivalent to taking 27 million cars off the road – effectively the entire UK private car fleet.

Transport is the biggest source of UK greenhouse gases, around 26% in 2021, with the report finding that fewer commuting journeys, along with lower electricity and household energy consumption, would be the driving factors behind such a fall in carbon emissions.

“By eliminating a day of commuting, you’re drastically reducing the carbon footprint of a large portion of the population,” Fletcher said.

“So whether that’s not using their cars, because they’re not commuting in the morning, and even down to not using public transport, even though we know using public transport is a greener way of travelling.

“So it comes down to by removing a day of commuting for people, you’re able to cut carbon emissions.

“The challenge is going to be how do we make sure that it is done in a way that doesn’t negatively then also impact businesses.”

Easing NHS pressures

The report also further reinforces the idea of the benefits of having more free time outside of work by working fewer days, claiming there would be a ‘shift towards low-carbon activities’ such as reading, exercising and spending time with family.

Having more time to do these activities, particularly the latter two listed, could have positive knock-on effects for people’s physical and mental health and also their ability to care for elderly or sick relatives.

All of which could ease some of the pressures facing the health and social care system in Wales.

A report published last year found that one of the biggest factors increasing pressures on GP and mental health services was the lack of social care capacity to look after patients within the community.

With a four day week, the relatives of those who often require help from community care providers would have more time to take on some of those duties, such as cooking meals, doing housework, or just providing a source of company, according to Ms Godden.

“The four day week can give people more time to care for people,” she said.

“I think there’s an interesting loop there that we’ve got a sick population that needs looking after and we’ve also got a crumbling NHS.

“And we’ve got a lot of people that would be happy to be there but they just don’t have the time.

“So on that day [off], we could see a lot of people being able to just check in on elderly relatives or if they’ve got a family member with an illness.”

Feedback from the UK trial also suggests that this is a real issue for workers and that the four day week would help them find the time to care for friends and family.

45% of those surveyed prior to the pilot felt that they did not have enough time to look after elderly, disabled or infirm relatives – this dropped to 23% by the end of the scheme.

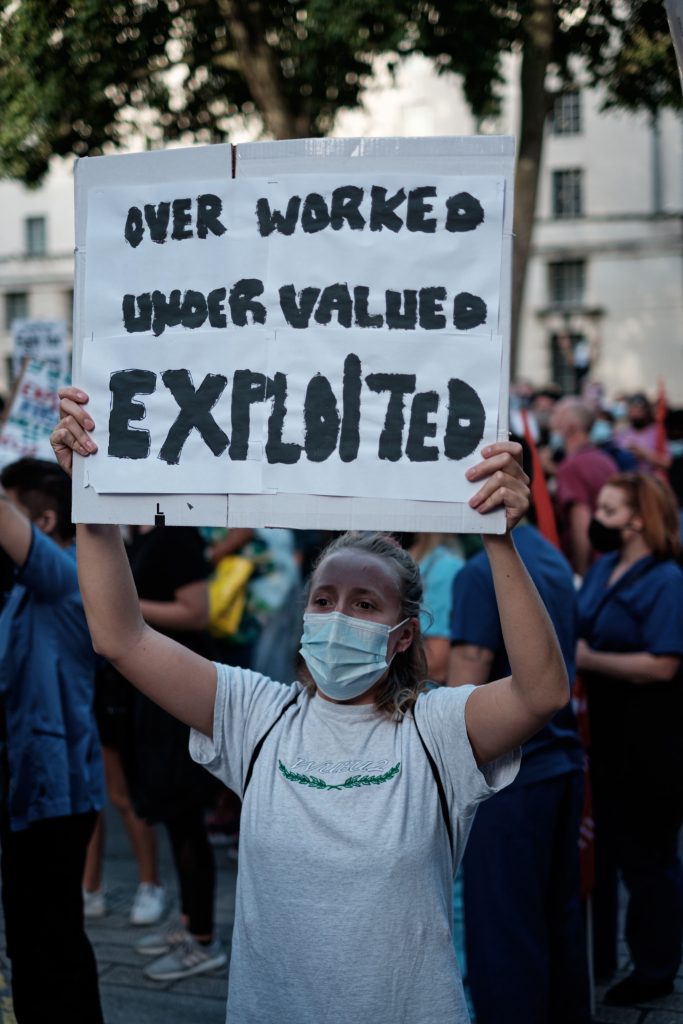

Another of the key pressures facing the NHS is low morale among the workforce amid the cost of living crisis and increasing pressure on the service.

As a result, nurses have taken industrial action while other staff are moving into the private sector or leaving the industry altogether.

Along with better pay, Plaid’s Luke Fletcher MS believes that the four day week could be one way of improving conditions for healthcare workers.

“One of the biggest issues with the [NHS] workforce, aside from pay, is workplace conditions and being overworked,” he said.

“So the four day week is potentially one way of giving capacity to people who are working in the NHS and other places to get a better work life balance.

“And because ultimately, you think that’s what most people want, they want their work to live not to live to work.”