While British-born Chinese children are increasingly using English as their first language, their Chinese parents still habitually talk with them in Mandarin. How do these Chinese expatriates balance their children’s learning of two languages?

Five-year-old British-born Chinese girl Cindy, dressed in a scarlet Chinese dress, said in fluent Mandarin, “I wish you all good luck and health, and a prosperous Year of the Tiger.” On the wall nearby hang two red couplets with Cindy’s Spring Festival greetings in neat calligraphy.

Cindy was celebrating Chinese New Year with her mother Sharon, who had lived here since 2001. Despite being away from the motherland for many years, the 38-year-old has a deep affection for Chinese culture and language, which is especially evident when she teaches her daughter Mandarin, traditional culture, poetry, and calligraphy. Talking to her daughter in Mandarin since she was born, Sharon deeply recognizes the importance of passing on the mother language to the next generation.

However, parents like Sharon who teach their children Mandarin from an early age may be uncommon in Cardiff, although most of them still habitually talk with their children in Mandarin at home.

“Many overseas Chinese here mainly run Chinese restaurants and markets. They spend very little time with their children, let alone teaching them Mandarin,” says Sharon, “While their children spend most of their time in school, where they are completely exposed to English, it is not surprising that they are rusty in Mandarin.”

It is not only Chinese expatriates who are showing concern over Mandarin inheritance. In Cardiff, the International Mother Language Monument(IMLM) project held its annual celebration on February 21st to promote mother language protection with expatriates from all over the world.

“It’s important for every expat community to pass on its mother tongue to the next generation, they have cultural and linguistic ties to the mother country,” said IMLM chair Anwar Ali.

However, expatriates still face obstacles in passing on their mother tongues to the next generation. Ahmed, a Bangladeshi immigrant, said his children understood Bengali but could not speak it. “They understand me by hearing, but they answer me in English. That is why Bengali is being lost here.”

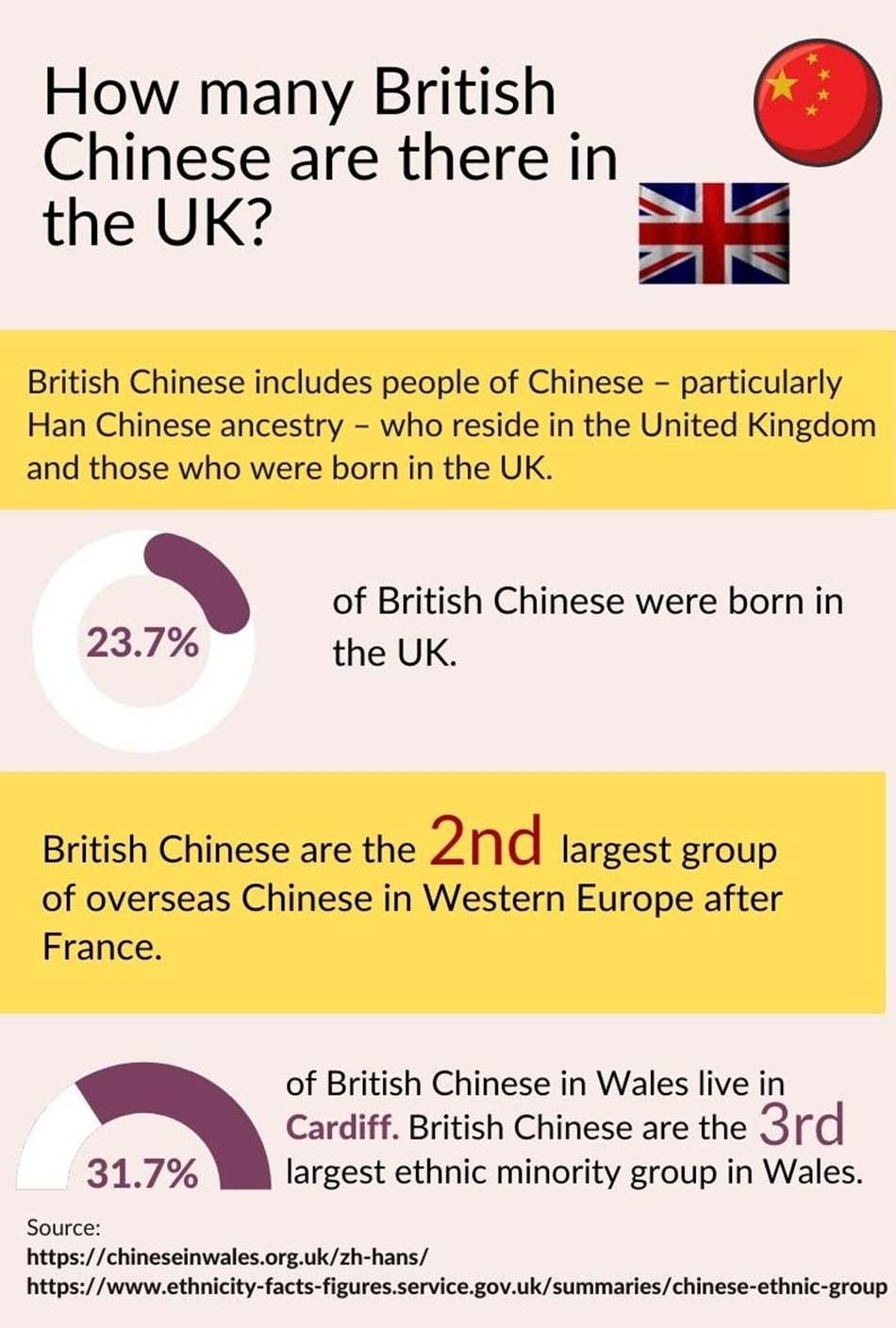

This problem arises more prominent among the Chinese expatriates, the third-largest ethnic minority group in Wales. Wu Xiumei, a Chinese restaurant owner from Dalian, China, finds that many children speak Mandarin with their parents at the dinner table, but when the children gather together, they only speak English.

“Parents expect their children to speak Mandarin more often, but because they are immersed in English all day long, they still use English as their first language, not Chinese,” says Wu.

Liu Jing, a Mandarin teacher from China, says the lack of Mandarin courses in Cardiff specifically for British-born Chinese children is another reason why Mandarin is losing ground among Chinese expatriates from generation to generation.

“There are many Mandarin courses for British people, such as Cardiff Confucius Institute providing Mandarin lessons and Chinese culture lecture series,” says Liu. “But there are very few lessons for British-born Chinese.”

Liu launched a Mandarin course for British-born Chinese children in 2020, but terminated the course after only two academic years. She believes the difficulty of teaching such courses, and the low enrollment rate, are reasons for their unsustainability.

“The Mandarin foundation of British-born Chinese students is uneven. Some children can’t speak Chinese at all, but some mixed-race children can, so it is difficult to have a unified Chinese curriculum,” says Liu. “Besides, sometimes there are only 4-5 children at most in each class, the cost is too high to make a profit.”

There is no shortage of Chinese communities in Cardiff which helps British-born Chinese children to learn Mandarin in a Chinese environment. However, according to Cardiff University’s Ph.D. candidate Zhou Mengxing , also the mother of two kids born in Cardiff, many parents do not want their children to integrate into such communities because the areas with large Chinese communities in Cardiff and the UK are mostly lower-middle-class societies.

“Most well-educated Chinese parents expect their children to pursue elite careers as lawyers and doctors, so they think it gives more value to children’s career development to learn more competitive skills such as computers and math than Mandarin,” says Zhou.

Despite this, Zhou believes that there is no problem with basic communication in Mandarin for those British-born children, given that mandarin is a “heritage language” they are born with and can learn quickly at an early age. “My husband and I communicate daily with our daughter in Mandarin. We don’t deliberately teach her but she can naturally talk with us in simple Chinese.”

Zhou mentions that her 3-year-old daughter often shakes her head and says “No.” “I don’t like it.” in Mandarin to show strong emotion if she gives her something she doesn’t like. However, Zhou says she does not expect her children to speak Mandarin as their first language as they grow older.

The inheritance of Chinese culture is even more impossible for Chinese children born in the UK, according to Zhou, who explains that it is difficult for them to develop in-depth identification with Chinese culture as they grow up and form values in the west.

Nowadays, Sharon introduces her daughter to Chinese culture every week in the form of storytelling and teaching some Chinese songs and ballads. They also have weekly video calls with Cindy’s grandparents in China, during which her grandmother teaches her first-grade Chinese textbooks online.

But she is also aware that the western upbringing makes it a hindrance for her daughter to be proficient in Chinese unless she brings Cindy back to China and studies a Chinese-style education, which is also one choice for her daughter’s future planning.

“For now, she can cope with this bilingual learning pattern, but for the future, I think it’s up to her to decide which is her priority,” says Sharon.