Fears for the game after a year in lockdown breaks the sports habit for youngsters around the city

“THERE are no markings on the pitches and the goalposts are down. That’s really sad to see. We’re in March, which is usually the height of the football season.”

Dean Ford is describing the image that has become the norm on park football pitches up and down the country.

While elite football has soldiered on through the coronavirus pandemic with no supporters and stringent protocols, the grassroots game has been pushed to the side. The impact has been disastrous, not just for adults but children as well.

As part of the Football Association of Wales’s Return to Play regulations, youth football returned in September after a six-month absence, with the rule of 30 in place and clubs only allowed to play friendlies.

But it was only a three-month reprieve, as when Wales entered an Alert Level 4 lockdown in December, junior football was suspended again along with all other non-professional domestic competitions.

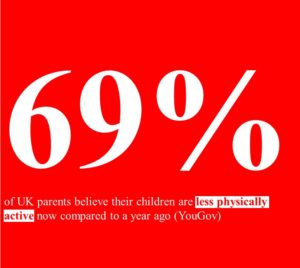

We are beginning to see the longer-term effect of these regulations and last week, Youth Sport Trust revealed 69% of UK parents believe their children are less physically active now than they were a year ago.

Chief Medical Officer guidelines recommend that children should be doing an average of 60 minutes of physical activity every day, but 79% of parents reported that their children are currently doing less than this target. 11% say their children are currently doing no activity at all.

Before the pandemic, football pitches up and down Wales were packed with children and the FAW Trust was well on its way to achieving its goal of getting half of young people in the country playing football once a week. But in the last 12 months, these pitches have become closer to desolate wastelands.

Ford, who coaches the under 12s boys team at Cogan Coronation and is soon to be club chairman, says: “Some of our boys don’t just play for us, they’ll play for the county, they’ll play in academies. So they have gone from playing five or six times a week to absolutely nothing.”

Gareth Morgan, head of coaching at Llanrumney YC Football Club, says: “Few parents feel safe letting their kids go out and play in the streets, so the two or three hours a week that they used to spend at the football was their only real form of exercise.”

Discussing levels of physical activity among children during lockdown, Morgan says: “If my son was wearing a Fitbit, I doubt he would average 7,000 steps a week which is just horrific.

“Mental health wise, he would tell you he’s fine because he’s talking to his friends online and he’s happy playing on the computer, but his physical health is real worry for us as his parents. We’re having to force him to come out on a walk.”

“They’re on a screen pretty much all day,” says Casey Warren, manager of Fairwater FC, of his two sons. “They’ll wake up, have their Zoom classes and in between each lesson they will play on the computer. We have some gym equipment in the house so they use that every now again, but they’re doing nowhere near as much as physical activity as they used to.”

While last summer presented children with opportunities to be more active, the winter lockdowns have proved more of a problem.

“In the summer, kids could be out in their gardens with their parents and it didn’t make too much of a difference,” Ford says.

“More parents were on furlough and had more time to spend with their kids. Now there are fewer parents on furlough and the weather has got worse and it gets dark earlier.”

Morgan adds: “We sign our kids up for sports clubs so they’re not sitting in their bedrooms on their phones all day. But the pandemic has forced us into not only allowing that to happen, but not being able to give them any other option.

“What else can you do with an eight or nine year old who is used to playing football four or five hours a week? Particularly in these winter lockdowns, the weather has been so bad you can’t even take them for a kickabout.”

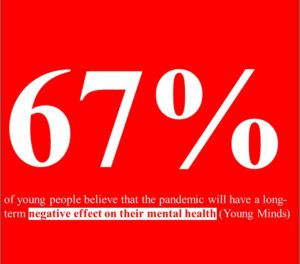

Not being able to play football has had an impact on children’s mental health as well.

“I speak to parents quite often and I know kids have been struggling,” Ford says. “Mentally, the pandemic has had a huge impact on them.”

A survey by UK charity Young Minds found that 67% of 13 to 25-year-olds believe the pandemic will have a long-term negative effect on their mental health. While not directly related to the amount of physical activity that children do, a lack of exercise undoubtedly has an influence.

“We know that the last year has taken a significant toll on young people’s wellbeing,” says Ali Oliver MBE, Youth Sport Trust chief executive.

“That so many parents have seen a decline in young people’s engagement in physical activity is extremely concerning. Active young people are healthier, happier and better equipped to learn.”

Clubs have tried to adapt to the circumstances and Zoom fitness sessions have become the norm, while inter-club challenges have proved popular in order to try to keep children active.

“I can’t speak highly enough of how well my coaches have dealt with it,” Morgan says. “They’ve done Zoom sessions and kept in contact with parents, giving them drills that their kids can do in the garden.”

Warren says: “We’re doing a club challenge where all the junior teams have come together to attempt to do 25 marathons in a month as a collective. But it’s the same people taking part each week.

“It seems like the ones who are really into football, they’re engaged and will do the runs, but my biggest fear is the ones who are not involved. I’m not sure they will come back when football restarts.”

That seems to be a shared concern across Wales. The statistics around current levels of physical activity among children are worrying, but the long-term effect could be even greater.

One parent, who wished to remain anonymous, said their children had been without football for so long, they had lost interest in playing. They are unlikely to be alone.

“The big worry for us at the moment is when next season comes around, people will have got out of the habit of coming to football and won’t return because they’ve found other things to do,” Morgan says.

“Some kids will have simply lost interest because they’ve been allowed to sit on an iPad for 18 months. The number of children that the game will lose is frightening. The decline in participation will be the legacy of the pandemic.

“The age group that I fear the most for is the one that was under 14s at the start of the pandemic, who will be under 16s at the start of next season. There were four leagues in our area in that age group last year. I would be amazed if there are even two next year. If you give 15-year-olds the excuse to not bother, they won’t bother.”

Children aged three to seven went back to schools in Wales in late February, while all primary school children will return on Monday along with those in qualifications years. That will only heighten the desire to see youth football return.

“These kids will go to school and they will be able to have a kickaround at break time, but they can’t go to football training,” Morgan says. “I’m not sure of the reasoning behind that.”

There is a frustration among coaches that there has been no clear plan for grassroots football from governing bodies. Even when the sport temporarily returned to park pitches in the autumn, the rule of 30 meant that many players at 11-a-side level had to stay at home to avoid matches being over capacity once coaches and officials were taken into consideration. At younger age groups, parents were not allowed to watch on from the sidelines.

“It’s hard to motivate the kids because we don’t have a restart date,” Warren says. “There is nothing to work towards or focus on.”

“There has been absolute silence from the FAW,” Ford adds. “We have heard nothing from them since they stopped football just before Christmas. Not even a message to say, ‘how are you doing?’. It feels like they have forgotten grassroots.”

In the first week of February, the FAW confirmed its intention to complete junior competitions for 2020/21 when Wales returns to Alert Level 3, but coaches had hoped that grassroots football would be cited in the Welsh Government’s review of the restrictions on Friday.

While not referencing football specifically, First Minister Mark Drakeford told WalesOnline that organised children’s activities will be reopened from March 27 for the Easter holidays, stating that “I want children in the school holidays to have things that they can do”. However he did not mention whether there would be any limit on the number of people allowed to be involved.

The FAW responded to the announcement, stating: “If the public health conditions continue to be favourable, football activity for Under 18s will return from this date [March 27].

“The FAW are awaiting clarification from Welsh Government on specific restrictions that may be in place for football activity to return for Under 18s and updated Return to Play protocols will be communicated as soon as possible.”

It is a sign that there is light at the end of the tunnel, but for many people involved in youth football it is too small a gesture that comes too late. Children are simply desperate to kick a ball, to pass to their friend and to score a goal.

“Just let them play,” Ford says. It’s not even about winning or losing. I just want to see kids smiling and having fun.”